1. Identify the basic elements in a game of your choice (actions, goals, rules, objects, playspace, players).

Game Analyzed: Carcassonne

Players: It’s a game that requires at least two players. There’s not too much to analyze here, except that the game is heavily player-reliant. As we’ll see in the next few points, the map leaves a lot of flexibility so no two games have the same map, and with that flexibility also come different interpersonal dynamics between the players: do I keep to myself in my area of the map, do I sabotage someone else’s projects?

Playspace: The playspace is the map, consisting of small square cards. All the players need is a flat surface on which to build their map. There’s a lot of freedom when it comes to building the map, although each game of Carcassonne contains the same 100-something cards, a myriad of maps can be created from those, and so the map will end up looking differently every time. The only key constraints that the playspace imposes are that all cards have to be used, and that the map that is created in the process has to be continuous with every additional card being adjacent to an existing card in a compatible manner (compatible meaning: city meets city, land meets land, road meets road).

Objects: Other than the cards which I have categorized as a part of the playspace (although one could argue the playspace is just the idea of a map constrained by some rules, with the cards themselves being objects – I’m a bit torn), there are the soldiers and a scoreboard. The soldiers are used to signal ownership (of a city, street, or land), and the scoreboard is used to keep track of a key factor of the game state: the number of points a player has already achieved. This is important as it relates directly to the goal of the game.

Rules: The rules are quite detailed, so I won’t go into great detail. But the most important rules, other than the ones described in the Playspace section, are the following: Players alternate and pick one square (without seeing what it is), and place it on the map. When they put a square down, they can take ownership of any one of its elements (a card may have a land, and a city, and a street component). For every finished city or street, the player receives points, which are tracked on the scoreboard.

Goals: The primary goal is to build your own empire of cities, streets, and land, and receive as many points as possible. It is certainly a competitive game, characterized by the fact that ownership can be stolen from you if someone manages to attach your city/street to their city/street if they have more soldiers in it (that can overwhelm yours).

Actions: Anything the players can do in Carcassonne: pick a square and add it somewhere, put down a soldier (either on the land, or the street, or the city), and use future cards in future turns to strategically grow their empire to make as many points as possible.

2. As a thought experiment, swap one element between two games: a single rule, one action, the goal, or the playspace. For example, what if you applied the playspace of chess to basketball? Imagine how the play experience would change based on this swap.

I propose swapping the element of golf where players start out in different tee boxes depending on their physical attributes and skill levels with the element of Monopoly that everybody receives the same amount of money from the bank to start with. I imagine Monopoly would become a lot more fun, and a lot more instructional. Right now, I think Monopoly communicates the winner take all nature of capitalism incredibly well, and does create some idea in players for how fast luck can change. Especially early on, before there’s a clear land-owning monopolist and a few poor paupers, investing a lot of money into property can be what turns you into the winning monopolist, but also what may cost you everything you have if you’ve invested too aggressively and are suddenly faced with a bill to pay.

But according to Ellen Terrell (2022), Elizabeth Magie, the inventor of the original Monopoly, the game is supposed to teach people the following:

“The object of this game is not only to afford amusement to players, but to illustrate to them how, under the present or prevailing system of land tenure, the landlord has an advantage over other enterprises, and also how the single tax would discourage land speculation.”

Introducing an element of luck, where the richest/most able (that is, in real-life) player would start from the worst possible spot in the game with very little money would add an element of hardship and randomness that would underline more closely how the real world works: not every person starts with the same amount of physical and social capital: some inherit an apartment, some even inherit land, others inherit nothing but debt. Making that glaring inequality more obvious, yet in this playful way, would likely lead people to engage with the message and societal commentary the game wanted to advance more, already before the game starts when the question is: which of the players at the table had it easiest in life and is the most business-savvy. While risking to turn people off wanting to play Monopoly since that may be an uncomfortable discussion, I think the game would become more random and thus more fun. The inequality, inside a game environment, may well be entertaining: I suspect people who start out with more money would have more fun, and those starting with less would be up against a frustrating attempt at overcoming the difficult hand they were dealt, just to be even more proud of winning should they manage to do so.

Most importantly, the added randomness may make the advantages land-owners/monopolists have feel even more unfair, and as such do a better job at transporting the message the game was initially intended to transport.

3. Pick a simple game you played as a child. Try to map out its space of possibility, taking into account the goals, actions, objects, rules, and playspace as the parameters inside of which you played the game. The map might be a visual flowchart or a drawing trying to show the space of possibility on a single screen or a moment in the game.

The game I often played is called BrändiDog.

Background Information:

BrändiDog is a popular Swiss game that is similar to the American game Parcheesi and the classic Indian game Pachisi. It is a partnership game typically played by four players, with two players forming a team. The game has a board, cards, and colored marbles representing the players. Each player has 4 marbles in a start position on the side of the board. The board is circular with tracks around the perimeter. Each player has a home track (towards the center of the board), the end goal is to get all 4 marbles in the home track. Players play in teams of two. They move their marbles by playing cards they have drawn from two standard decks of cards, including jokers. If they play a 7, they get to move their card forward by 7, for example. Some cards have special effects (e.g. swap marbles). The team of two that first has all their marbles in their respective home tracks wins the game.

Rules:

- Start: To begin, players draw a card from the deck and move marbles according to the value drawn. The movement is counter-clockwise.

- Card values: Each card has a specific movement value, or a special action:

- Ace: Get out of start area.

- King: Get out of start area.

- Queen: Move 12 forward.

- Joker: Can be any other card.

- Ending the move: The journey ends by moving into the center of the board, and this requires an exact card draw.

- Team play: Partners can and should help each other. For example, a player can use a Jack to switch one of their marbles with their partner’s marble if it benefits their gameplay. While each player moves their own marbles, they have only won once both they themselves and their team mate have all their marbles in their home track.

Space of Possibility (and possible player actions):

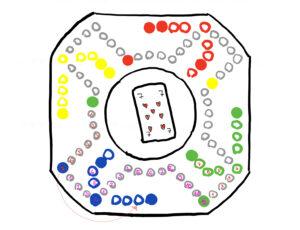

The space of possibility is virtually endless depending on what cards get played and how many marbles are out on the field at any moment. So I’ve decided to map the space of possibility at a specific moment (see sketch below). At this moment, it’s the Green Player’s turn. He only has a king and a 7 on his hand. The actions he could take: Play the king, get his last unused marble out, and block the way for everyone except himself. Or play the 7, and move one of the marbles that are out forward. She chooses to play the 7. Now, there’s two actions she can take (see red numbers): move the marble on the left side of the board forward by 7, thereby resulting in another action: sending the blue marble back to the start. This keeps the blue player from moving the blue marble to the home track. Or she uses the 7 to move her own marble to safety. What makes most sense depends on the cards blue has and may decide to play once it’s their turn (pink numbers). If blue has a Queen, it could use it to keep green from getting her marble to safety (i.e. home track). But if green doesn’t send the blue marble right in front of its home track back to start, blue may well get it to safety in their next turn.

4. Pick a real-time game and a turn-based game. Observe people playing each. Make a log of all the game states for each game. After you have created the game state logs, review them to see how they show the game’s space of possibility and how the basic elements interact.

Real-time Game:

I observed (a video of) a card game where all players have a stack of cards in front of them, face-down. They don’t know what’s in their stack. They go around the table (clockwise). The player takes the card at the top of their stack, and turns it around (away from them, so the player sees its face last), and then puts it down in the center of the table (face-up) to create a new stack in the center. If the card is a number card, nothing happens, it’s simply the next player’s turn. If the card is a face card – i.e. either a jack (1), queen (2), king (3), or ace (4) – the countdown starts. If it was a queen, the countdown is 2, if it was an ace, the countdown is 4, etc. Let’s say it was a queen, i.e. the countdown is 2. That means the center stack belongs to the player who just played the queen, unless in the next two turns, someone else plays a face card, in which case the countdown gets reset to the appropriate value for that specific face card.

So now, it’s the next player’s turn. She has a 7. So it goes on to the next player. If this player had a number card, the first player (who put down the queen) would get all the cards as the countdown is now at zero. But let’s say this player’s card is a king. So the person playing the queen doesn’t get the center stack, instead the countdown is now reset to 3, and the game continues. If no one plays another face card in the next 3 turns, the center stack is his; he turns the entire center stack face-down, and adds them underneath the existing cards in his own stack.

What makes this interactive is that people can slam their hands on the cards in the center if the last two cards played are one and the same, and then the center stack is theirs. So the space of possibility when it is your turn is to put down a card (no agency there… since you can’t pick a card), or at any time in the game, the possibility is to notice faster than everyone else that two players in a row have put down the same card, in which case they can claim the center stack by touching the cards in the center faster than anyone else. Whoever is out of cards loses the game (but can re-enter while there’s still multiple other players in the game by acting fast and claiming the cards in the center), whoever is the only one with cards left in the end wins. The game relies on speed: people play their cards really fast, and it often looks like the people are close to a fist-fight when two of the same cards land on top of each other, especially if someone else already got excited about getting to collect the cards in the center and adding it to their stack since they played the last face card and the countdown was almost zero.

This is a really simple game, but the cards and player’s actions interact to make it a fast-paced and entertaining (and loud) game that only needs a deck of cards to be played, no matter where people are located.

Turn-based Game:

BrändiDog: Impossible to create a log of all the game-states (several thousand), but in simpler terms, there’s the following key states:

- Player has opponent right behind him (less than 13 fields distance), needs to increase distance for greater safety.

- Player has no opponent behind him or in front of him.

- Player has opponent in front of him, less than 13 fields distance, will try to attack and send him home.

These 3 states, combined with the cards you have on your hand and your opponent has on their hand decides what is possible and what is wise to do. Of course, since one can have multiple marbles out and since there’s multiple opponents, multiple of these states may overlap. But mainly, it’s an interaction of the players where their actions are to try and move forward (with more stress, i.e. playing bigger cards in case 1 and more relaxedly in case 2) around the board to get closer to their goal (bring marble to safety in the home track) and if possible – if they have a card that gets them to exactly where an opponent is sitting – not simply move forward but also inflict damage on an opponent by sending them home.

5. Citations and Author’s Notes:

Terrell, E. (2022) The very fascinating Elizabeth J. Magie: Inside adams, The Library of Congress. Available at: https://blogs.loc.gov/inside_adams/2022/09/elizabeth-j-magie/ (Accessed: 21 October 2023).

AI Disclosure: Used ChatGPT 4.0 to scan the submission for errors in sentence structure and spelling. No other AI tools used.