- Identify the basic elements in a game of your choice (actions, goals, rules, objects, playspace, players).

The game of choice is Checkers.

Actions: In Checkers, the primary actions involve moving pieces diagonally on the game board and capturing the opponent’s piece by jumping over them.

Goals: The goal is to capture all of the opponent’s pieces or to put the opponent into a position where they cannot make any other legal moves.

Rules: The rules of Checkers outline how pieces can move. Typically, pieces can only move diagonally forward by 1 square at a time from one dark square to another, unless there is an opponent’s piece in a diagonal square followed by an empty space after. In this case, the player can capture the opponent’s piece by “jumping” over the opponent’s piece into the vacant space. The player can chain together multiple jumps if there are multiple opponents’ pieces positioned with empty spaces after them. Players can only move their pieces diagonally forward until one of their pieces reaches their opponent’s side, in which the piece is “crowned” a King and can move either forward or backward diagonally.

Objects: The objects in Checkers are the pieces themselves (one color for each player’s pieces). There are 24 pieces, 12 of which are of one color and 12 of which are another.

Playspace: The playspace in Checkers is typically an 8×8 game board of squares with alternating dark and light squares.

Players: The players are the 2 individuals controlling the checker pieces. Each player controls 12 checkers of the same color. Checkers can be played only by 2 people, and is appropriate for all ages.

- As a thought experiment, swap one element between two games: a single rule, one action, the goal, or the playspace. For example, what if you applied the playspace of chess to basketball? Imagine how the play experience would change based on this swap.

In Chess, pawns can only capture opponents pieces diagonally, similar to capturing pieces in Checkers. For this thought experiment, I will consider applying the “jumping” rule from Chess onto pawns in Chess. Thus, pawns can now hop over opposing pieces and chain together multiple captures.

Such a change would significantly alter the dynamics of Chess by making pawns much more powerful and strategic. Pawns, which otherwise can only move forward and capture diagonally 1-square at a time, can now bypass opposing pieces and move much faster down the game board. This would allow for much more aggressive early-game strategies, as these pieces could potentially clear paths for other pieces, would become the only type of piece that can capture multiple opposing pieces at once, and would fundamentally reorient every existing chess strategy. Future strategies would now require many more mental calculations due to the pawns’ ability to move multiple times in one move. Games would realistically become faster-paced and more dynamic.

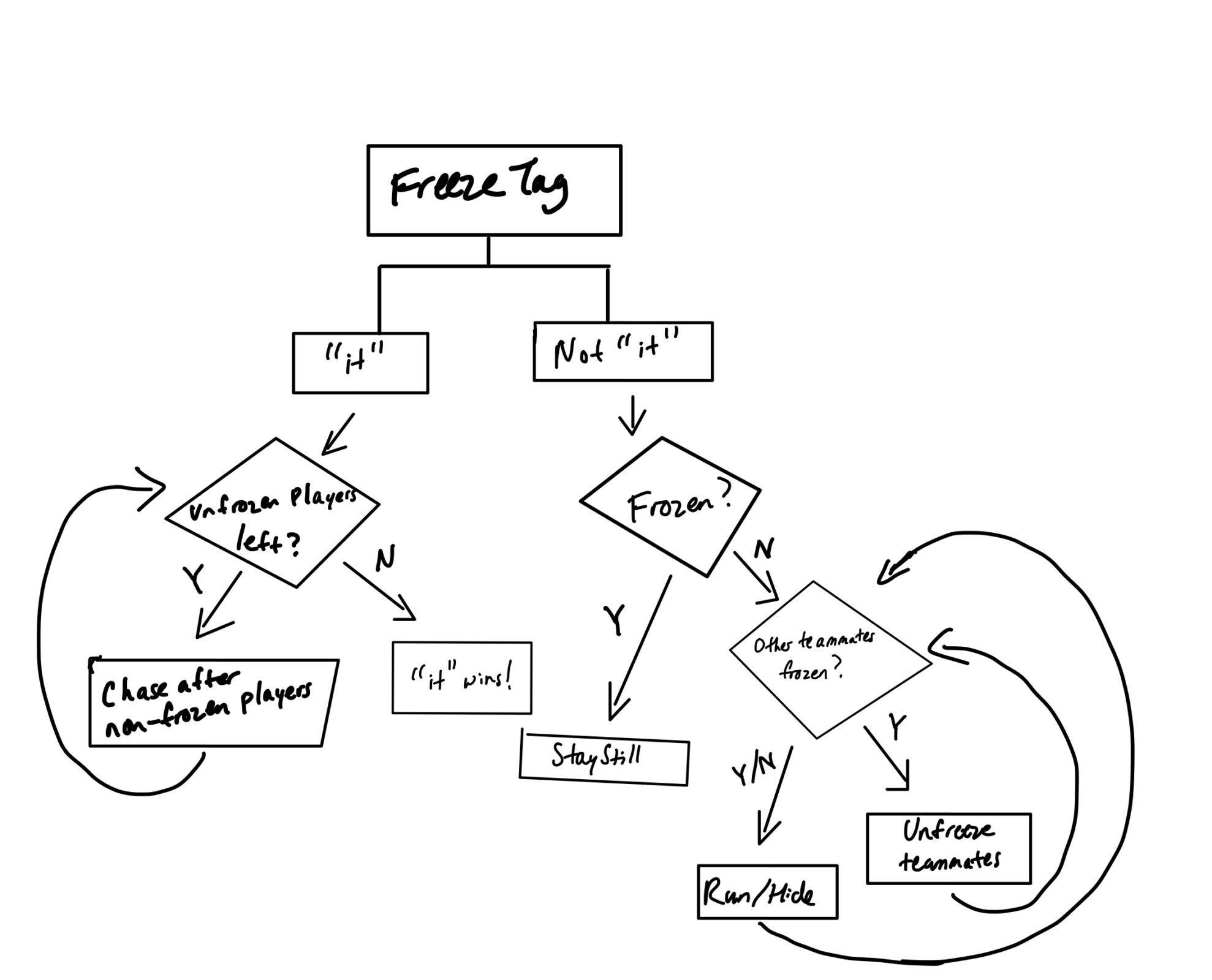

- Pick a simple game you played as a child. Try to map out its space of possibility, taking into account the goals, actions, objects, rules, and playspace as the parameters inside of which you played the game. The map might be a visual flowchart or a drawing trying to show the space of possibility on a single screen or a moment in the game.

- Pick a real-time game and a turn-based game. Observe people playing each. Make a log of all the game states for each game. After you have created the game state logs, review them to see how they show the game’s space of possibility and how the basic elements interact.

Real-Time Game: Rock-Paper-Scissors

| Round | Player A | Player B | Winner |

| Round 1 | Scissor | Paper | Player A |

| Round 2 | Rock | Scissor | Player A |

| Round 3 | Scissor | Rock | Player B |

| Round 4 | Paper | Paper | Tie |

| Round 5 | Rock | Paper | Player B |

| Round 6 | Scissor | Scissor | Tie |

| Round 7 | Paper | Scissor | Player B |

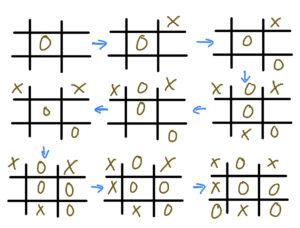

Turn-Based Game: Tic – Tac – Toe

Review

The real-time game of rock-paper-scissors was much more fast-paced and inherently limited the ability to think out strategy as players only really had a few seconds between the rounds to think of their next move. Tic-Tac-Toe, however, allowed for more time for user-strategic thinking due to the downtime between turns. Additionally, each player’s strategy was much more short-term-minded in rock-paper-scissors, with each action theoretically not having any limiting effects on future possible game states. On the other hand, Tic-Tac-Toe required much more strategy, as each player’s actions inherently limited the future possible game states for both players. The users methodically selected squares based on their ability to cut off the other players’ chances of 3 in a row while also setting themselves up for success many steps later. When the players both realized the game was unwinnable, they focused on preventing a loss, hence forcing a tie. The turn-based game of tic-tac-toe had a much higher number of possible game states, while the real-time game of rock-paper-scissors only has 9.