Identify the basic elements in a game of your choice (actions, goals, rules, objects, playspace, players).

I’ll be selecting Crossy Road which is a simple arcade game based on the classic joke of “Why did the chicken cross the road?” (a joke I didn’t truly understand until recently haha). For reference, a free-to-play version can be accessed here.

- Actions: The player can move forward, left, right, or backwards. Additionally, the player can collect coins that are then used to unlock new character models.

- Goals: The main goal is to survive for as long as possible where every forward move increases the score. A player can also strive to attain more coins or character models.

- Rules: The player must keep moving across the road to survive. If the player exits the constraints of the map or is hit by a moving obstacle the game restarts.

- Objects: The objects include the character model that the player controls, the coins that are collected, and the obstacles that the player can land on and interact with.

- Playspace: Within the game itself, the space is a procedurally generated road that is constrained on both the left and right sides. The world is generated as the player moves forward.

- Players: Single Player

As a thought experiment, swap one element between two games: a single rule, one action, the goal, or the playspace. Imagine how the play experience would change based on this swap.

For this exercise, let’s imagine what would happen if we apply the absorption rule of Agar.io to the game of tag. In Agar.io, the experience is player vs player where the players control their individual circles in an attempt to become the largest circle – if the player’s circle is larger than the one they are touching, they absorb it. Likewise, in tag, every player competes for themselves with the goal to not be tagged.

However, in swapping this rule, the game of tag would transform into a more collaborative experience where once the player is tagged, they must join arms with the people previously tagged. Together, they will then try to tag everyone.

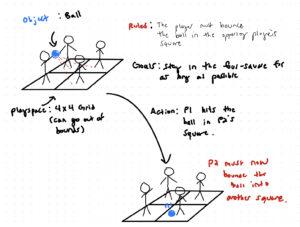

Pick a simple game you played as a child. Try to map out its space of possibility, taking into account the goals, actions, objects, rules, and playspace as the parameters inside of which you played the game.

For the simple game, I’ll be taking a look at four-square, a game I often played during recess as a child:

Pick a real-time game and a turn-based game. Observe people playing each. Make a log of all the game states for each game. After you have created the game state logs, review them to see how they show the game’s space of possibility and how the basic elements interact.

Turn-based game: Cornhole

- Setup: Each player gets four bags and stands at opposing ends.

- Inning: P1 and P2 take turns tossing bags until all 8 bags are played.

- Within each inning the bag either:

- Lands on the platform

- Goes into the hole

- Miss the platform and lands on the ground

- End-Round

- Players grab their bags and reset the playing field

- Win-Condition

- Players win once they reach a certain number of points

From observing this, the game’s space of possibility emerges from the variations in how the player decides to land their bags and the communication between the two players. While it is a two player game, the action of another player does not interfere with the opposing player’s action. As a result, it becomes a race to reach a set number of points where the points of the opposing player and communication can influence player action.

Real-time game: Air Hockey

- Pre-Round: Each player gets an air hockey paddle and a player starts with the puck.

- Round:

- Player hits the puck

- The puck is floating through the table

- The puck can bounce off the sides of the table, hit the paddle, fly off the table, or enters the goal

- End-Round

- Round ends when the puck enters a goal or flies off the table

- Players reset and round repeats

- Win-Condition

- Players win once they reach a certain number of points

In air hockey, the players and the puck are constantly moving. As a result, the game is more dynamic as opposed to having a discrete turn that affects the game state. Throughout the game, the player must keep track of the position of the puck, their own paddle, and the opposing player’s paddle as they execute an action. This requirement to stay focused and the fluidity of the game is what makes air hockey an exciting real-time game!