Doki Doki Literature Club is a visual novel that tells the story of a male high school student who reluctantly stays in his literature club because of the romantic possibility between him and the club’s members. Team Salvato developed the game and was originally played on itch.io and later distributed through Steam. I played on my laptop through Steam! In this critical play, I’ll discuss my critiques of the game and how I played the game as a feminist.

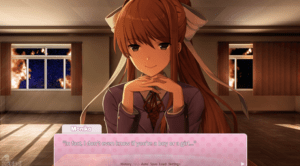

The game initially appears to be a dating simulator. It’s reminiscent of harem-style gameplay where all supporting NPCs are romantically interested in you, the main character. Over several days, you can make choices that determine your closeness with certain characters, opening up more and more scenes with certain characters. This plays very deeply into certain feminine archetypes, like the tsundere character who secretly cares deeply for you, the quiet, soft-spoken girl who likes books, and the childhood best friend who has always loved you. At first, it feels very silly as a woman playing the game since the pronouns used for the MC are very obviously masculine, and thus makes it clear that this game is not for you— it’s for a man. This changes later when the club’s president Monika breaks the fourth wall and proclaims her love for you, the player, not the MC. The game offers you quite a bit of false agency, alongside real agency. Some of the decisions you make are meaningful in that it determines what scenes you get to see with certain characters but others are fake. The more I engaged with the mechanics, the more I realized that things were not as they first seemed. Some choices forced you to only choose one character while others let you choose any character with no effect on the result of the decision.

The game offers you quite a bit of false agency, alongside real agency. Some of the decisions you make are meaningful in that it determines what scenes you get to see with certain characters but others are fake. The more I engaged with the mechanics, the more I realized that things were not as they first seemed. Some choices forced you to only choose one character while others let you choose any character with no effect on the result of the decision.

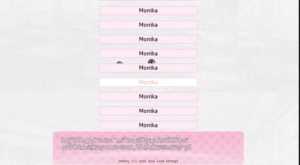

One choice I found fascinating was when you had to choose between three characters but when you hovered your cursor over any choice that was not Monika, the cursor would automatically move to hover over Monika. I tried to click another option, Yuri, and in doing so, I got another screen with a creepy pair of eyes, warbled text in a glitched textbox, and the choice “Monika” over and over again. Agency may feel like an illusion in this game at times, but I think by offering the choice in the first place and still accounting for “wrong” options, the game is exactly offering the kind of realism mentioned in the Chess reading by forcing the player to rethink their agency in the game and thus in the world around them.

This game disrupts the status quo and by doing so, has attracted an audience of both female and male players. I actually find this game very feminist — it completely flips the dating simulator genre on its head with the psychological horror twist and gives more personality to the characters beyond the stereotype. Monika at first seems just like the popular smart girl, but once we realize she’s self-aware and omniscient within the game, we are able to hear an hour-long dialogue of her thoughts about the world (vegetarians, where the game is supposedly located, spicy food, feeling small in the big world, etc) while the player figures out how to delete her file from the game. Monika even saves you from Sayori in the normal ending. Even if the game continues its narrative of all these girls being in love with you which is very harem-like, the other mechanics and aspects of storytelling really change the meaning of the game the further you dive into it.

Improvement-wise, I thought some of the dialogue in the beginning could have been more engaging. I had heard about the “other” parts of the game (not in detail because I didn’t want my experience to be spoiled) and felt like I was just skipping through the initial dialogue to get to the “good stuff”. Overall, I found that the game was very good at making me feel super on edge (off-tune music, glitches, jumpscares) and from a game designer’s perspective, the game really utilized music to its fullest. Some of the off-tune notes in random scenes really caught me off guard and also directed me to the fact that something was deeply and terribly wrong. The main theme music was so pretty and it really did feel like the game was normal at first, which made the changes later so much scarier. A really nice short play!

Signing off,

Annabelle

Discussion question: Why give a player agency, and why take it away? How does this add to the meaningfulness and narrative of the game? How exactly does agency contribute to one’s realization of it in the game and in the real world?