Game, Creator, Platform, Target Audience

This week, I played one night, hot springs on Steam, developed and published by npckc. Its intended audience is people of all ages, but specifically people who are willing to engage in potentially sensitive and personal topics around the experiences of a transgender woman in Japan.

Formal Elements and Types of Fun

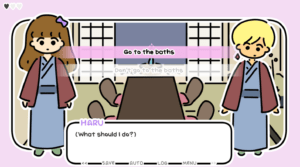

one night, hot springs is a single-player game with a single player vs. game interaction pattern, and an objective of exploration through narrative as we learn more about Haru. The main actions are clicking to move the dialogue forward (/backward) and making decisions about what Haru should do, which drive the story forward and result in different endings. The game intends to have fun through narrative and sensation, and it succeeds as it unfolds Haru’s interactive story that has the potential to induce powerful emotions.

Playing as a Feminist

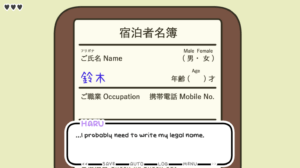

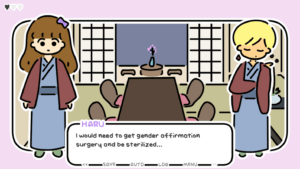

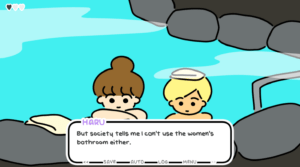

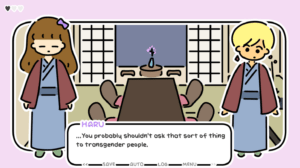

For me, playing the game as a feminist meant reflecting on the various connections the game had to feminist concepts. The entire theme/premise of the game engages with feminist ideas already, as it tells a story that is “not just about women but also about characters who face the adversities set forth within our mainstream cultures” (59). Haru certainly falls into this category as a transgender woman, especially in the setting of Japan where she faces many adversities both legally and socially. The game intertwines feminist theories, especially as it “provides a space where the audience is not passive but instead playing an active part in the retelling of the story” (60). At every decision point, the player has an opportunity to reflect and make a decision that will inform the outcome of the game. The game also incorporates agency at decision points because the player can choose to “act and speak back to systems of power” (61). While I did not see explicit aggression against Haru through the course of the game when I played, there were certainly “microaggressions” and not-so-fun things that came up as a result of societal expectations and current structures/oppression in place. At each decision point, I tried to choose the choice that aligned with speaking up and advocating for Haru, which ultimately resulted in a positive outcome.

Clever Decisions/Potential Improvements/Critiques

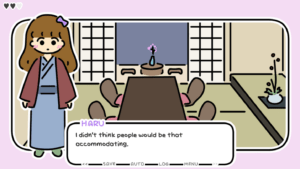

The designer made clever decisions in terms of creating a game that was engaging and replayable because of its seven possible endings based on the player’s choices. The decision points were also skillfully chosen, as they related to feminist concepts discussed above, and the reduction of the decisions to two simple choices for the most part meant that novice players were not overwhelmed. However, an area for potential improvement might come with a critique around its depiction of the world as very kind, even more kind than expected. This might relate to the particular ending I had, but it seemed like the narrative itself was also kept relatively tame. This could be a purposeful decision, and there were certainly moments of disappointment on some level, but I wonder if there could be potential downsides if this story potentially leaves out some of the hardest parts of the transgender experience.

Discussion question: how do we balance accurately representing experiences of traditionally oppressed groups with giving hope for a “kind world” and not “overwhelming” players with negativity?