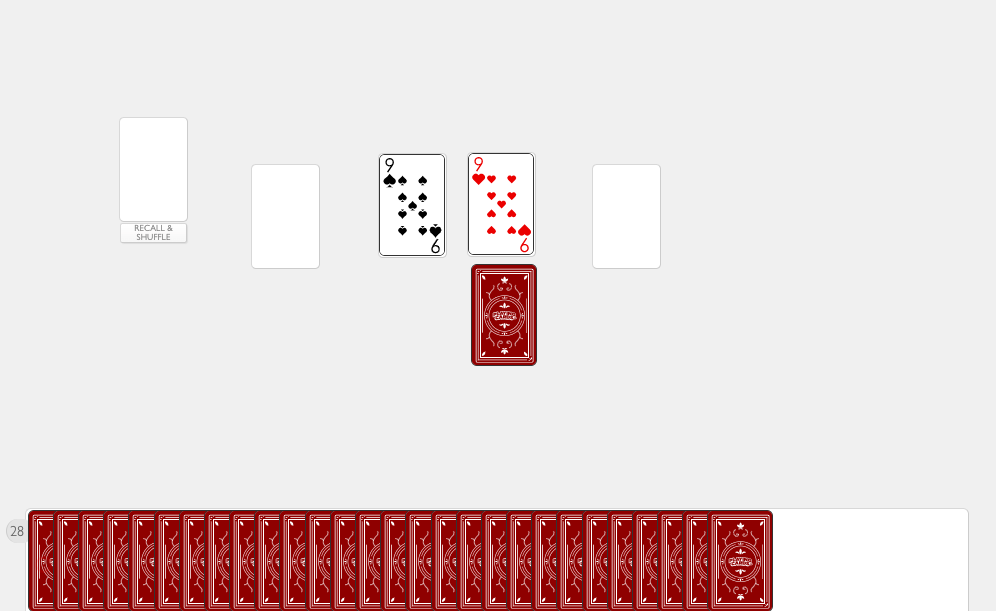

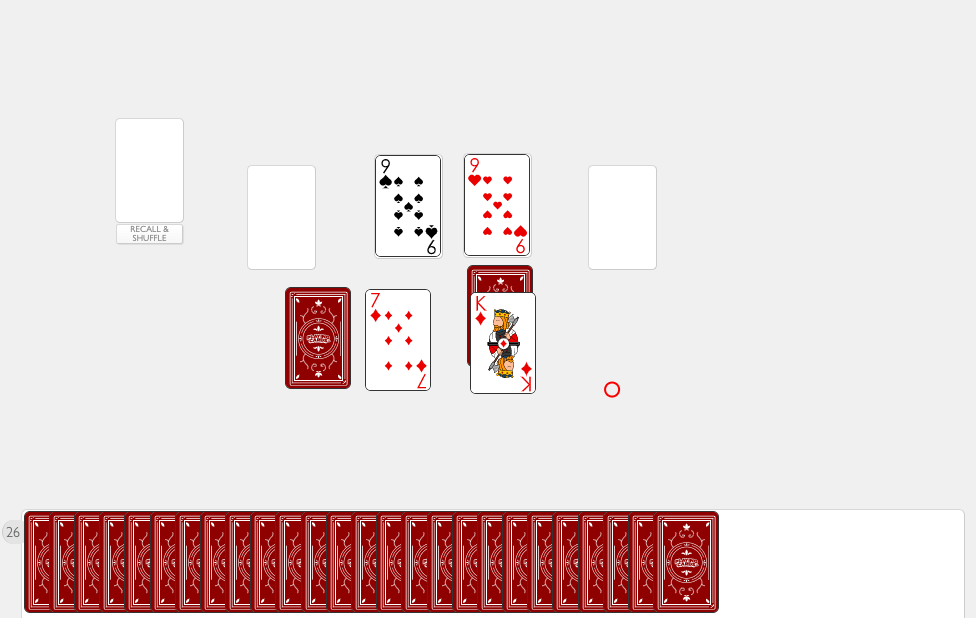

This week, I played War. I played with a friend on an online card game simulator:

The main mechanic in war is putting down a card, face-down. When the card that both players put down are of the same rank, players then put down an additional card face-up, and an additional card face-down, and repeat until one player ends up with a higher-ranked card.

War does not inherently put people at significant risk for addiction, compared to other games of chance and probability, because of the lack of monetary involvement. The game is mostly played for entertainment purposes, and doesn’t include wagering real money. In my experience, I found it the opposite of addicting. I think back to Randy’s lecture on randomness, specifically when he talked about swinginess — do results vary widely in outcome, and if so, by how much? In War, there isn’t much of a spectrum that the outcomes land on, but rather employs a binary structure: you either collect the cards or you don’t. Additionally, these outcomes are entirely based on chance, so there is no strategy to steer their own fate in the game. In fact, at many points, my friend and I would go back and forth on who had more cards, only to end up leveling back out to a split deck again (my friend had 26 cards, and I had 26 cards). My friend made a comment that voiced her frustration: “All that just to end up back where we started?” It felt impossible to get to a point where one person would have the entire card deck in their hands, because every time one of us would get closer to having a full deck, there would be several rounds in a row which would get us back to square one. War is a game of pure chance — there is little to no autonomy in how those cards are chosen and played, so players may feel discouraged over time. In this way, War doesn’t involve skill or critical decision-making, but is rather wholly dependent on luck.

Compared to other games involving chance, such as Poker or Blackjack, War’s lack of monetary involvement reduces the psychological attachment to the game. The wins and losses evoke little emotion because they don’t hold much weight in the game. In Poker or Blackjack, a player feels in control and has room to strategize their best plays in order to win money. Winning money feels good, and it feels addicting. However, in War, because there is no strategy involved or other mechanic besides putting down a card, face-down, players will likely feel helpless for the majority of the game. There are rarely any negative consequences, but even when players do experience them, since there is no money at stake, the weight of the consequence does not feel as heavy as losing money in a game of Poker or Blackjack. Designing Chance: Addiction by Design explains that, “The uneducated gambler… may walk away from a machine at which he has had no luck, only to become upset when he witnesses another patron win on the very next spin — feeling that the newcomer has ‘stolen’ what rightfully belonged to him.” Games that require players to wager money naturally makes them feel more connected to the game because they’re risking what they’ve worked hard to earn. The “uneducated gambler” may feel a sense of entitlement or unfairness when witnessing someone else winning, while simultaneously feeling as though they could be a winner themselves (and thereby playing another round). They may believe that their luck will change and they’ll eventually get to their desired outcome as long as they keep playing the game. This anticipation of a potential reward, in conjunction with the frustration from seeing others win, can contribute to the addictive nature of games such as Poker, Blackjack, and other games that involve gambling. In contrast, War doesn’t involve wagering money and involves little to no agency for the players. As a result, my friend and I often felt disconnected from the game. If I put down a card that was a lower-ranked card than my friend’s, the loss didn’t feel like a true loss to me, because I knew how volatile the game was. Chances are, in a few rounds, I’d be the one with more cards. On the flip side, wins didn’t feel as captivating in War either, since the game requires a collection of all the cards of the deck to win the entire game. Overall, I think War is a decent game and I admire how accessible and straightforward it is, but I’d argue that the game is not addicting, and is a game of pure chance.