The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom (TOTK) is an action-adventure game on the Nintendo Switch, intended for everyone ages 10+. It was directed by Hidemaro Fujibayashi and produced by Eiji Aonuma. Although it’s labeled as an action-adventure game, the player can’t reach or succeed in any of the action without completing the hundreds of puzzles incorporated throughout the game.

What I especially love about the puzzles in TOTK is that they don’t feel like long, tedious puzzles with predefined expectations (which is how I feel about typical puzzle games). Instead, the puzzles are embedded into the game’s open-world mechanic, resulting in a game experience that is uniquely the player’s and doesn’t adhere to any expectations preset by the gamemakers. This experience makes TOTK one of the best discovery games on the market.

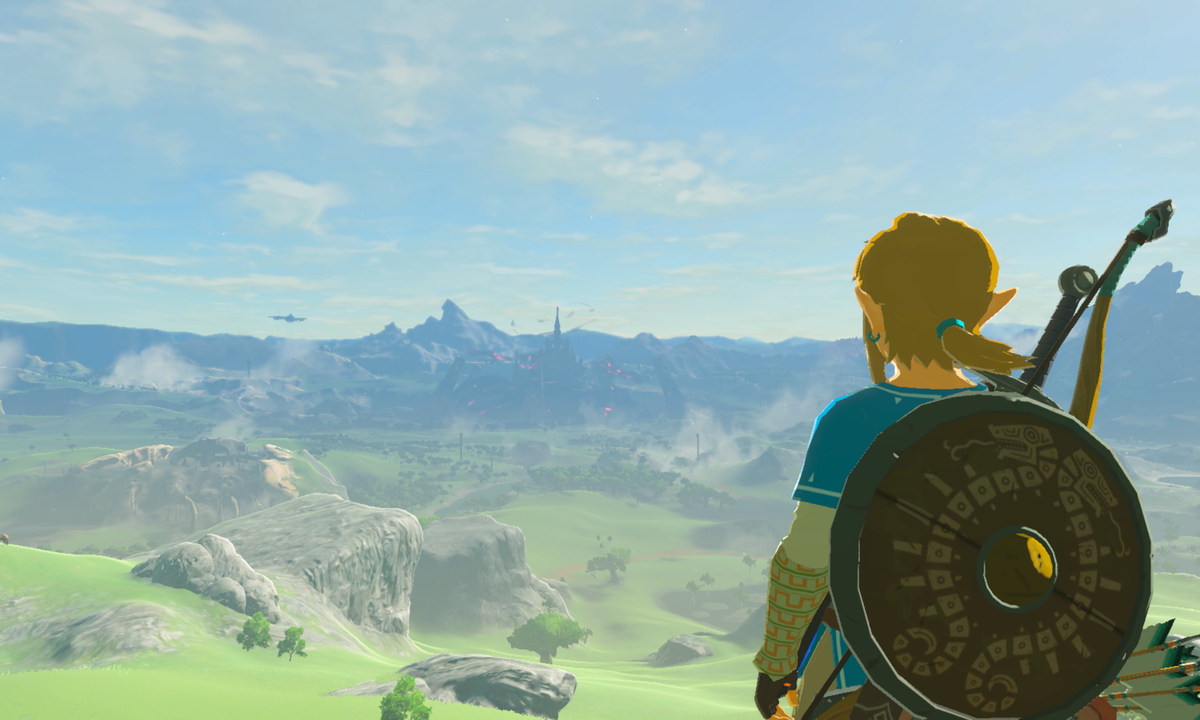

To illustrate this, let’s examine some of TOTK’s formal elements. TOTK and its predecessor, Breath of the Wild, are known for their strong aesthetic of discovery due to the game’s architecture of an open-world environment and the mechanic of a player being allowed to freely move about and interact with the world.

While the main character, Link, is given an overarching objective (i.e. finding Zelda), exploration is encouraged in order to find the resources, such as Link’s abilities, weapons, food, etc., necessary to do so. The best of those resources, however, cannot be unlocked or found without completing puzzles. The main way these puzzles are presented are through Shrines.

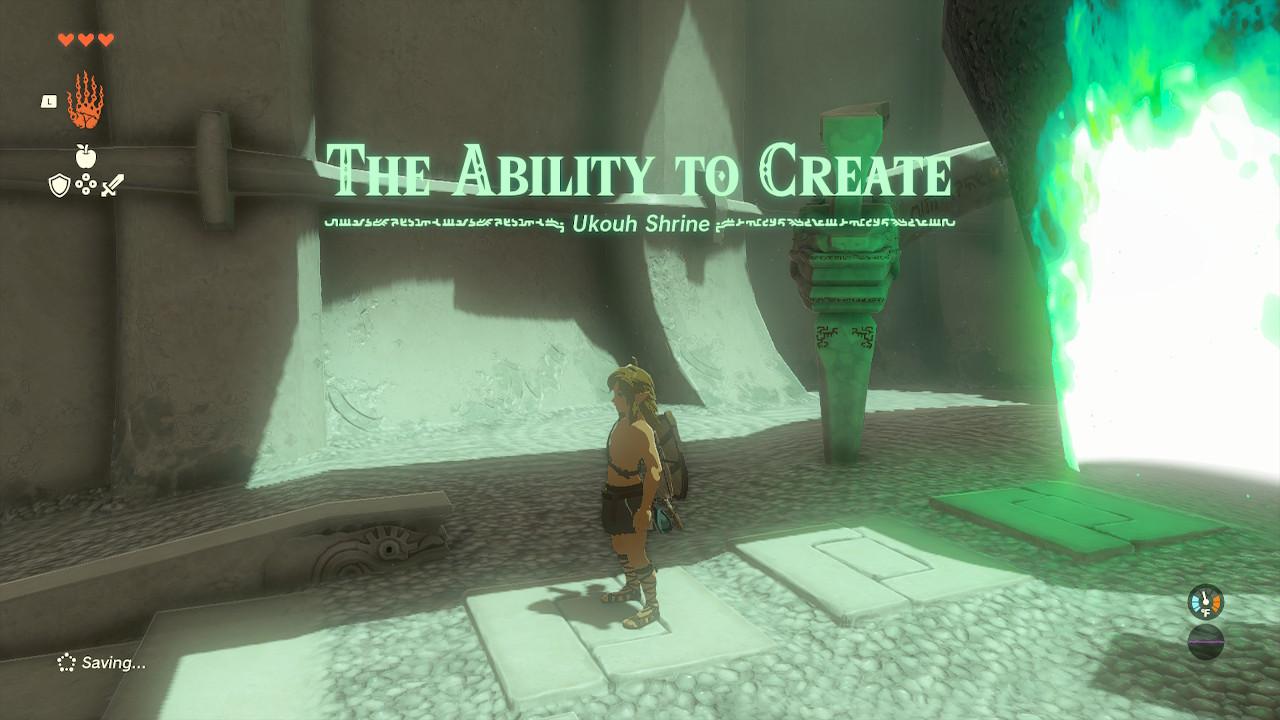

Upon entering a Shrine, its name is displayed, oftentimes providing a crucial hint about what is necessary to complete it. In this case, Link has just unlocked the Ultrahand ability, allowing him to move and combine objects in the environment. Thus, the title hints at using this new ability, creating the dynamic of a player continuously thinking about the name of the Shrine and how they can use it to guide the rest of their actions in the puzzle, providing an excellent balance of both direction and freedom.

Above, I had to cross the gap. There were several objects at my disposal, highlighted in orange. Eventually, I figured out how to use Ultrahand to put the objects together to create a hanging platform that I could ride across the gap. While the developers expected the player to create something, it was up to the player’s own creativity to determine what resources to put together. Maybe there’s another solution to this puzzle that incorporates those two balls highlighted in orange in the background (below).

While certain Shrines are necessary to complete to progress in the game’s main narrative, you’ll run into puzzles throughout the open-world environment. Not all puzzles in the open-world need to be solved to beat the game, but they often result in a chest being unlocked that contains a valuable resource to the player. So, although open-world puzzles are optional, I choose to explore and complete these puzzles so that I can get better weapons and find in-game collectibles. It’s also just more fun, in my opinion, figuring out how you can apply Link’s abilities to make new discoveries in the open-world. For instance, my desire to keep finding new resources created my dynamic of constantly pressing the L trigger to see which objects I could use the Ultrahand on and potentially build with, such as this sailboat I made to cross a large pool of water.