The Stanley Parable is a PC game by Davey Wrenden and William Pugh. Most of the gameplay is walking, and it is this mechanic—along with the constant presence of a narrator—that unveils the story to successfully elicit narrative and discovery types of fun.

The Stanley Parable opens with little information as to who Stanley is and the world that he’s in. All we know is that Stanley works a boring office job, and now all of his coworkers have suddenly disappeared. It is up to the player to walk around and examine the office to try to piece together what happened. Like many walking simulators, this lends itself to the discovery type of fun—players come back to the game to continue walking to new locations and discover more clues to the story.

Where The Stanley Parable differs is in its use of a narrator whose speech is influenced with by your choices. A common way to play The Stanley Parable (and how I played it), was to constantly do the opposite of what the narrator suggested I should do. Not only did this add to the discovery type of fun by breaking the fourth wall and allowing me to discover worlds beyond the actual world of the game (ie the warehouse or camera rooms), but it created an extra layer of narrative that was quite meta. The story shifts from Stanley’s life and his missing coworkers to a commentary on his (and the player’s) relationship with fate and choice. Walking itself becomes an act of protest in the game (depending on where you choose to walk). Due to this integral aspect of the game, the target audience for The Stanley Parable is most likely older teens and above, as it may be harder for younger children to grasp the philosophical aspect of the game.

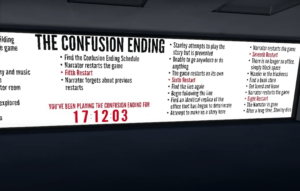

Although I think the game is extremely well-written and accomplishes its goals very well, I think something that could potentially improve player experience is allowing users to take in and dwell in the different endings more. I sometimes found that I’d barely be able to properly experience an ending and take in how I got there before I’d have to restart. This would sometimes kill the narrative type of fun because it felt as if certain plot points in the overarching story weren’t fully developed.