CS247G P1: “I Swear”

By Raghav Ganesh, Abena Ofosu, Elysia Smyers, Flynn Traeger

Artist Statement:

“I Swear!” is a social game designed to foster a sense of camaraderie and connection between players. With its themes of authenticity, creativity, and trust-building, the game encourages participants to engage in a playful and intimate exchange of personal anecdotes and experiences. As players share their unique stories, they offer glimpses into their lives, as well as empathy through putting themselves in each other’s shoes when reading off a card that isn’t theirs.

The essence of “I Swear!” lies in the balance between vulnerability, competition, and playfulness. As participants write down their experiences and prepare to defend them, and any others written on cards they may pick up, there is the possibility for storytelling, laughter, and disbelief. This vulnerability creates a platform for empathy and bonding, as players come to appreciate each others’ varied experiences. At the same time, the game’s dynamics foster a lively atmosphere in which players playfully compete to earn votes for telling the most compelling story.

We hope that “I Swear!” is a celebration of the power of shared experiences and empathy. Through laughter, storytelling, and playful competition, the game aims to create an environment where players can connect, fostering a positive atmosphere for deepening relationships and personal growth.

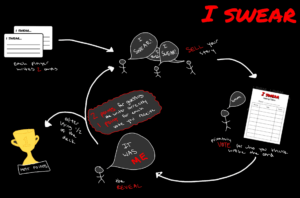

Concept map

Elements and Values:

-

- Structure Summary: The game’s simple structure, which involves writing down personal experiences, shuffling cards, and defending the actions described on the cards, provides a clear and accessible format that keeps the game flowing smoothly and all players involved. This structure allows all players to focus on the storytelling and the interpersonal dynamics at play.

- Players, Objective, Outcomes, and Boundaries: The game is multilateral, with the objective of earning as many points as possible for either telling a compelling story or guessing who originated the story. The outcome is non-zero sum in order to keep the dynamics more playful and avoid an atmosphere that turns toxic from becoming too competitive. The game’s boundaries are within the group in which the players are sitting.

- Time Constraints: The two-minute writing period and the 30-second defense time limit encourage players to think quickly and succinctly, fostering a fast-paced and dynamic gameplay experience without being too pressured. These constraints also level the playing field, ensuring that no single participant can dominate the conversation.

- Interactive Gameplay: The game’s interactive nature, which involves players asking questions and evaluating the truthfulness of others’ stories, requires active engagement and creates opportunities for deeper connection.

- Secret voting: The use of voting tables to record votes before announcing them prevents players voting choices from influencing others. Additionally, this element adds a non-threatening element to the game, making it less confrontational and easier to keep lighthearted, encouraging players to remain open with one another.

- Rules and Procedures:

Testing and Iteration History:

We playtested different iterations of our game on four separate occasions, each with 4-5 players external to our group.

During our first playtest with other 247G students, we played a very rudimentary version of our game, in which our initial ruleset was different to that which we later finalized. In this iteration of the game players simply wrote down something they hadn’t done before on a blank piece of paper which was then shuffled into the deck. When it was a player’s turn they pulled out a piece of paper from the deck and tried to convince everyone that they had done it. The game’s rules’ use of the double negative, wherein players had to lie about something they hadn’t done, seemed to be a source of confusion. Some playtesters also added that the game was very similar to “True Confessions” by Jimmy Fallon. We did however see that players were enjoying the game and were laughing and making jokes throughout.

Before our second playtest, we had made cards with “I Swear,” our game’s name written on one side to ensure that all players wrote on the same side of the card. We wanted to try the same ruleset again to see if the confusion from our prior playtest was an issue stemming from the game mechanics. In this iteration of the game, we saw that players managed to pick up the rules of the game quickly. In this playtest, the primary feedback we got was to modify the rules such that gameplay would become more personal. The suggestions from this playtest led to the change in rules which our final game version uses. Now, we have players write true statements about themselves and put them into the deck of cards. Players would then draw a card from the deck and convince others that they have done what is on the card. In doing this, players can learn more about each other and guess whom the current “truth” being discussed belongs to. In this playtest we also got more feedback in terms of balancing between the player’s storytelling and other players asking questions. We were also told that incorporating some form of secret voting might help with enhancing the gameplay by removing bias in voting as well.

In our third playtest, we gained much more feedback, which led to larger changes in our game’s rules. We realized over the course of the playtest that the player who wrote down their true experience on the card would recognize if another player was attempting to convince others of a story based off of their card. This led to situations where one player was at a clear advantage in that round of the game, and questions began to arise regarding how that player should be playing. Should they reveal that this was their card, or should they simply play along? We then received feedback to have each round be centered around one card, where all players attempt to convince each other of the fact that they have done the story that is written down on the card. There was also confusion about the objective in general, so we discussed adding a points system.

We did one final playtest session with friends outside of 247G in which we were able to play multiple rounds in succession, making slight iterations each time. In particular, we were able to finetune our voting methods. Playing this many rounds made us quickly realize the need for a place for players to log votes and points. On the fourth round, we quickly drew up and distributed a “voting table” for each player to test. This tested very well with the players and is the same table as is in our final product. We were also able to validate that the new points system incentivized the intended behaviors and that the game dynamics worked just as well for friends as acquaintances. The group was made up of friends who were close before and going into the game, the playtesters said that it was going to be too easy for them as they knew each other too well. However, only in two of the six rounds played was the actual writer of the card correctly guessed. This was exactly what we had hoped for!

We were pleased as well with how playtesters received our final design. When asked what the design conveys to them, one player said “everyone’s going round saying I swear I swear I swear and there’s one truth in the middle of all the mess.” This was exactly what we wanted the packaging to convey: the chaos and noise that the game offered. Our desire for this energy, as encouraged with the packaging, matched how the gameplay unfolded in the final playtest, as well as their thoughts on our design, with one player even adding that the design shows “little white lies surrounding the bold, colorful truth.”

Important Links