Game Designers: Marielle Burt, Alyssa Li, Lucy Lu, Ada Zhou

Overview

Get Schooled! is a competitive card-drafting game designed for four to five players aged 10 and above, with a playtime of approximately 60 minutes. In this game, you are tasked with running a high school that adheres to a particular educational philosophy. You have three years to improve your school before sixth-graders in your district choose which high school to attend. To enhance the quality of your school, you must make choices such as hiring teachers, training them to teach unique courses, and running special projects while also trying to meet national mandates. The quality of your school will be determined by the total number of cards you play, the number of courses taught with your educational philosophy, and the number of students who choose to attend your school.

Get Schooled! has undergone several changes since its first design iteration earlier this quarter. Our goals were to finalize the game’s aesthetics and packaging, clarify learning goals and support reflection, and simplify rules while expanding storytelling. We identified these areas for improvement based on feedback from playtesters at the end of P3 and our own experience replaying the game. Below, we outline the core changes we made in each of these categories, as well as the final tweaks we plan to make based on our last playtest.

Finalize Aesthetics and Packaging

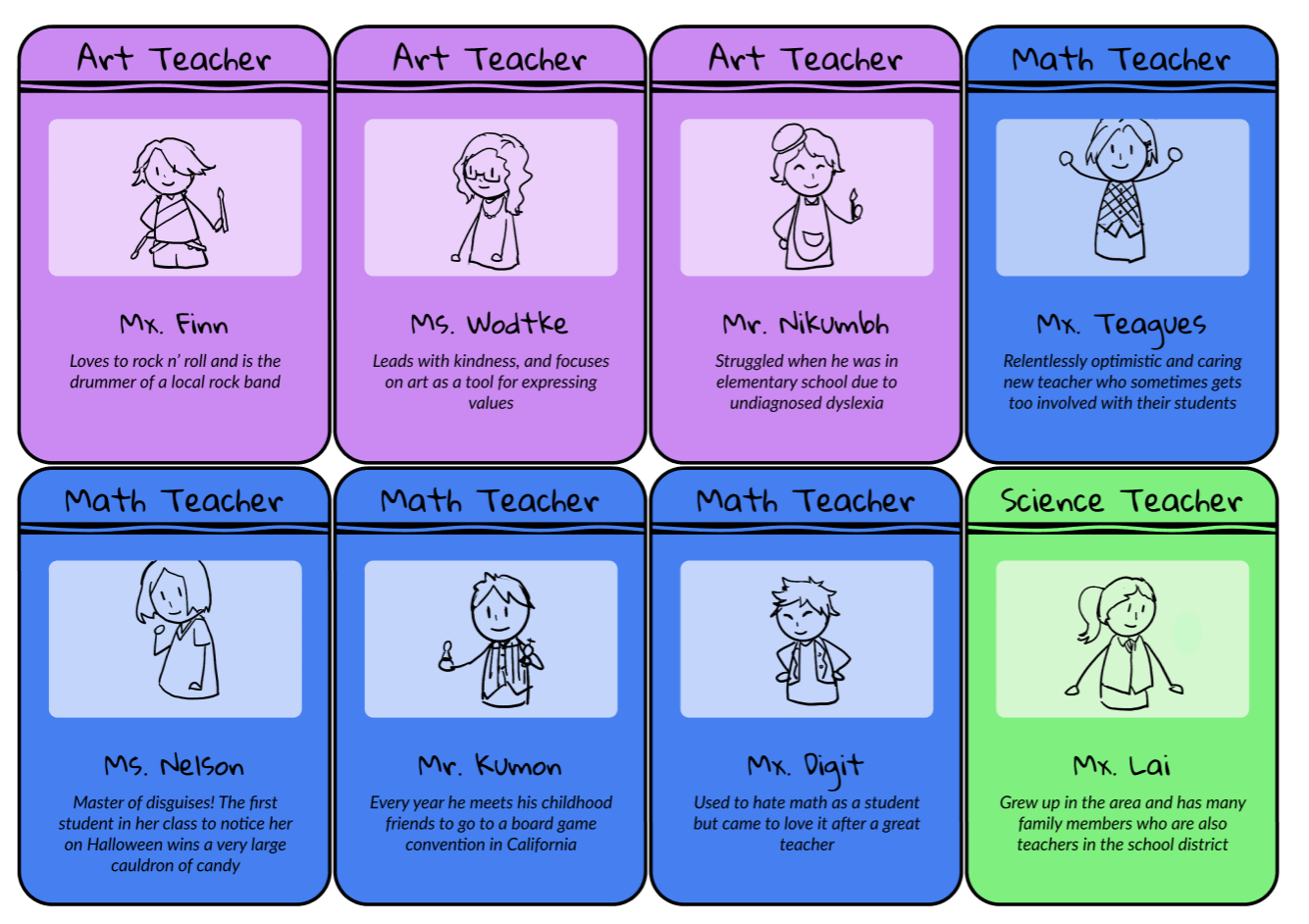

As narrative is one of the core types of fun in Get Schooled, we focused on creating an aesthetic and packaging that contribute to a playful, school-based narrative. We created drawings of all the teachers to help players imagine them as real people. These drawings are whimsical and childlike, reflecting our focus on student experience. We also decided to package the game in a tiny backpack and add a colorful label on the front with the game title. The novelty of this choice was a huge hit with our playtesters, who were “obsessed with” and “delighted by” the experience of opening the backpack. To accommodate this packaging, we resized our playing boards so they would fit inside the small bag.

Adjust Learning Goals and Support Reflection

Our previous version of the game was too complicated, so we simplified it by grounding our design changes in the core learning goals that are most important to us. We identified three types of learning goals: empathy, conceptual, and philosophical.

- Empathy: players connect to student needs and understand the value of designing schools with these in mind.

- Conceptual: players will be able to articulate the challenges of balancing different needs when designing schools.

- Philosophical: players understand different philosophies of education more deeply and how they impact school design.

Among these goals, connecting to student needs is our core focus. Thus, we altered our mechanics with this in mind. We also added reflection questions in the rule book to encourage players to discuss the connections between the game experience and the real-world challenge of designing schools.

Simplifying Rules and Expanding Storytelling

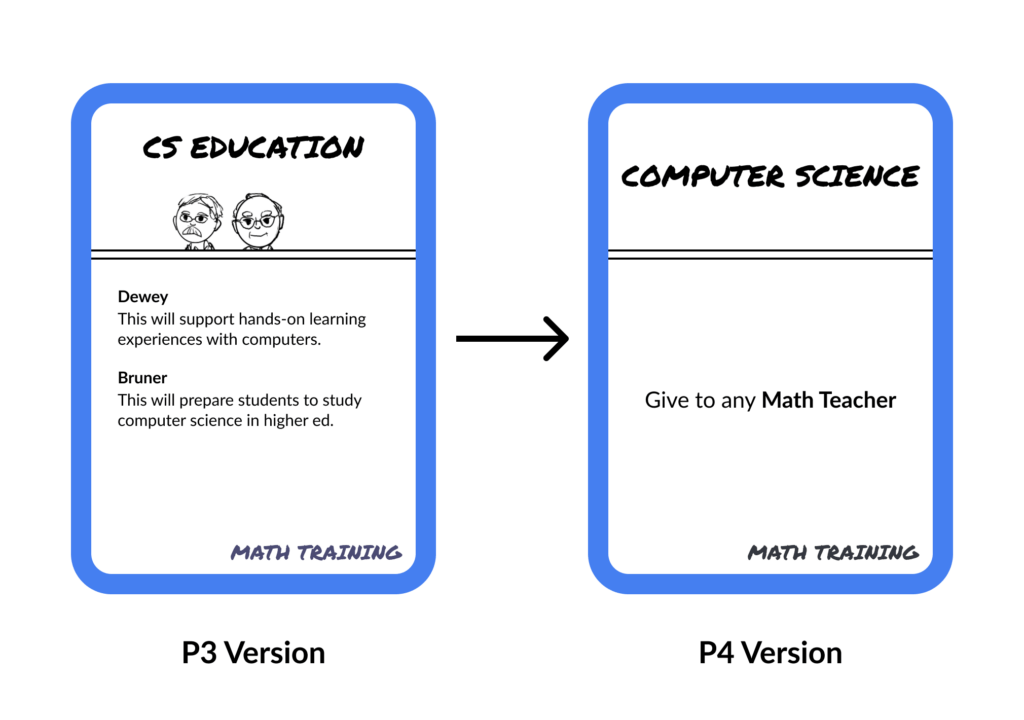

To focus players’ attention on student needs, we simplified the rules regarding the educational philosophy component of the game. We removed the specialty courses based on each philosopher (previously called Philosopher Courses) and cut the philosophy categories on each training card.

We also removed Funding tokens, which seemed to add unnecessary complexity.

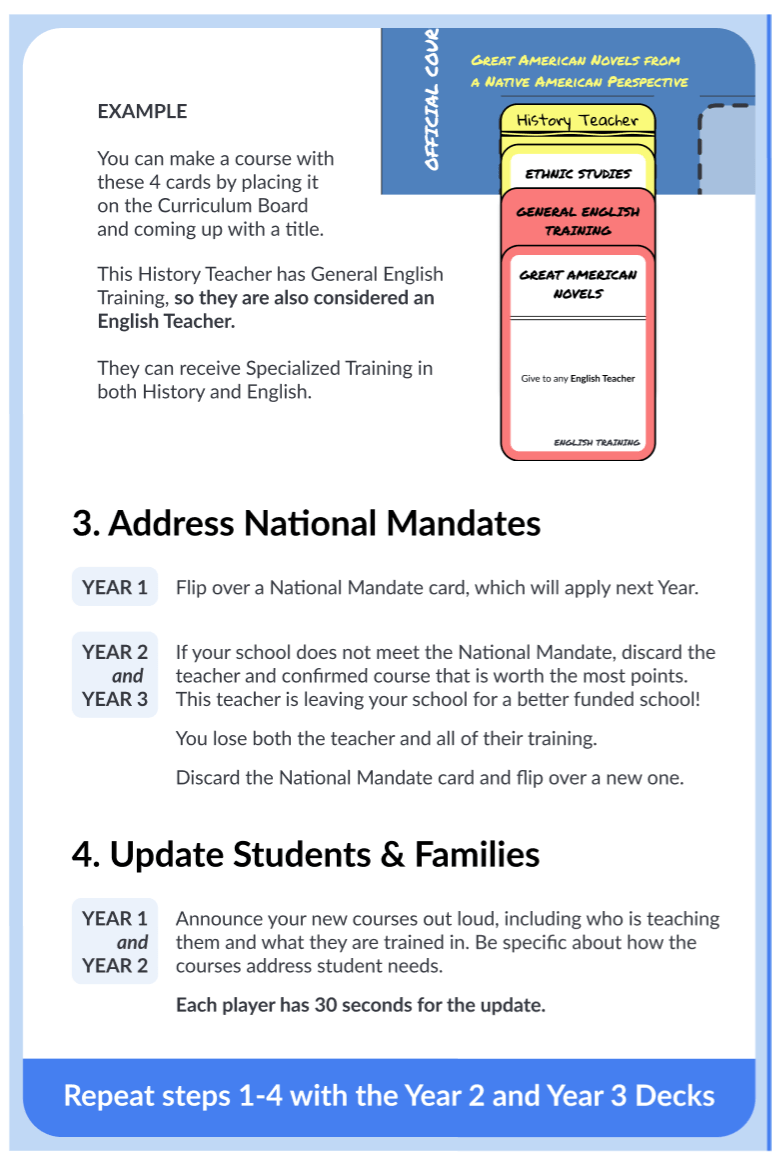

To replace these mechanics, we created one incentive for each philosopher based on the combination of courses they offer by the end of the game. Finally, we added a storytelling element at the end of each round where players “update students and families” about the changes they have made to their school and how these will support students.

Beyond shifting mechanics, we redesigned the rulebook to clarify the instructions and make them more visually appealing. We used the game Seven Wonders as inspiration for the layout of our rules, providing a “read as you go” style of rules that players can reference easily during each phase of the game. We also added more specific examples about the different types of actions players may take, offering visuals to support understanding.

Final Playtest & Next Steps

Our final playtest of Get Schooled! was a success, and involved lots of laughter and dramatic storytelling. Players seemed to connect with the importance of updating students and families of the progress in their school, offering specific examples of how the school would help particular students. Though we are very pleased with the playtest, we plan to make adjustments based on a few notes from players and our own observations. Then, we will hand the game off to the professor of Stanford’s Curriculum Construction class who has shown interest in using Get Schooled! as a learning tool. Our core takeaways from the final playtest and the actions we will take to address them are listed below:

- Players asked if they could add a training to an existing course.

- Action: we will add to the rules that they may add a training but they may not rename a course.

- Players made classes staked with over 4 trainings.

- Action: limit all teachers to 3 trainings max. Justify this in the rules as “preventing teacher burnout.”

- Players want more teachers.

- Action: add a few teachers into deck 2 and allow players to exchange 2 trainings for a teacher.

- Players shared it’s hard to keep all the student needs in their head.

- Action: create premade student cards with only one need, one strength, and information about their families.

- Action: add images to the student need cards representing needs and strengths to make them easy to recognize.

- Players struggled to keep track of the cards they passed.

- Action: create a playing mat and/or an area on game boards designated for players to place hands when they are ready to be viewed by the next player.

- Players took some time to understand the rules and start playing.

- Action: expand the rulebook to include an “example first round”

Overall takeaways:

Building games that reflect real-world systems, especially those as complex as the school system, is a serious challenge. Our initial designs were far too complex to actually help players grasp the ways that different elements of the school system interact with each other. Through our final redesign process, we learned that simplifying mechanics to amplify the most important learning goals is essential to creating effective systems games.