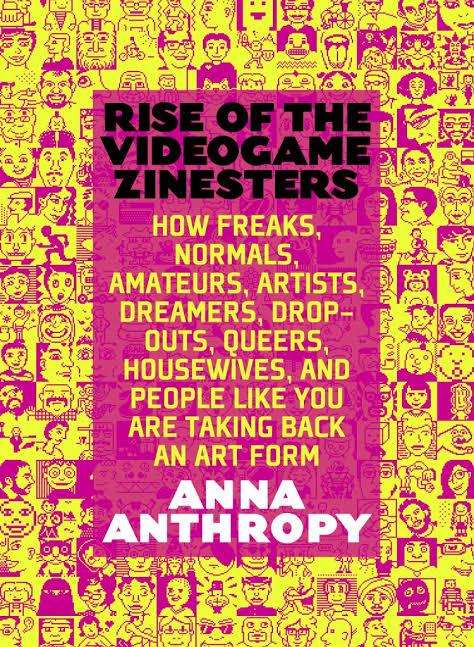

I reread Anna Anthropy’s Rise of the Videogame Zinesters (2012) with additional context in Gamergate (Adrienne Massanari’s “#Gamergate and The Fappening: How Reddit’s algorithm, governance, and culture support toxic technocultures,” 2016) and aspirational labor (Erin Duffy’s “Gender and aspirational labor,” 2015). Anthropy raises still relevant questions about access and innovation in video games, especially urging the multibillion dollar industry to move past its historically insular (predominantly cishet, white, masculine) culture to support games with a diverse array of voices and human experiences, especially from those on the periphery of the cultural mainstream. She draws from personal experiences as a queer transwoman who used low-code tools such as Game Maker and Twine to create and distribute her (narrative-based) games such as “dys4ia,” to assert that democratizing the artform will support a new generation of designers and storytellers to create more representative and interesting media. Zinsters spring from her long-voiced desires to explain how the value of games is located in the joy of “creating” itself and does not need to be justified as “art”: rather, games are an emergent medium to help people express themselves and create, in whatever quality or flavor they desire.

Following up from my response last year, I am emboldened by her vision of a more diverse, representative game design ecosystem that not only supports, but also rewards, innovation and personal stories from historically less heard voices, especially as there are evident examples (porpentine among them!) of how low-code tools for game design have led to a flourishing of zines and indie communities where this exploration is possible and can achieve modest to significant mainstream success. However, I am cautious of how conservative pushback in events such as Gamergate (~2014) and the Sad Puppies (~2016) challenge our notions of “progress” in forming more heterogeneous spaces for game design. Anthropy was arguing for more accessible platforms to support hobbyists and general creators, not necessarily professionals — for example, anyone literate can theoretically write a short story, why not expand that to games? — but we still see a continued dominance of large publishers and platforms for controlling market viability and in most cases, visibility with the “black box” of most platform feeds like YouTube. This in combination with what Duffy terms “aspirational labor” — how many content creators that succeed have historically, and continually, create hyper-feminized and -masculinized content to drive additional viewers the fastest (due to the ad revenue system) while initially working for FREE, leading to homogenous groups making more homogenous content for themselves — inevitably constrains what is available for the next generation to experience, draw inspiration from, and create works of their own. Some indie “unicorns” do have their mainstream successes, though the stories from the periphery are still facing their unfair share of trouble, with literal SWAT attacks called on underrepresented artists that do not fit the norms, even ones making interactive fictions about depression, or how even a hashtag like #ownvoices (books with characters from underrepresented groups where the author shares the same identity) becomes muddled when co-opted by marketing strategies. So even when zines flourish in their grassroots communities with audiences that truly care about them, they may not reach the level of prominence that would disrupt the next generation, and if they do, they are always in danger of being attacked, in several senses of the word.

That is all without delving into a discussion on the challenges of the “technical bar,” which Anthropy refers more to in the context of how breaking into industry tends to involve 1) developing advanced technical expertise in a speciality, and 2) working at a game company in difficult conditions where employees will be overworked and underpaid, and 3) spending their lives working on incremental features (often for games about “shooting people in the head,” or sequels to mega-behemoths). I think we should also consider the barrier of the required “unicorn” portfolio of proficiencies and intermediate knowledge of the skills involved in game design: storytelling, graphic and visual design, programming, marketing, and more. Tools like Twine are excellent for creating narrative-based games, and Scratch gently introduces fundamentals to student beginners, and even Unity has produced relatively beginner-friendly tutorials for making platformers (albeit with assuming some level of programming proficiency). The low-code and no-code options are sufficient for a hobbyist or beginner, and Anthropy emphasizes that a game does not have to be “good” to still be valuable as a form of expression. But these tools and tutorials have their conventions and drawbacks, and to amass the necessary skills (or the necessary team of wholehearted individuals) to take these stories and refine them to the level of disrupting the mainstream… to put it succinctly, that would require a lot.

However, we shall not fill this response with only doom and gloom: I love the dream of “carving new paths to game creation and distribution” and affirming shorter, smaller budget, self-contained games that explore ideas rather than the massive hits with hours of features and extensive depth. One of my most important takeaways from Meg Jayanth’s talk about “10 Ways to Make Your Game More Diverse” is how we are not alone in the quest to diversify the game design ecosystem, we are part of an ongoing conversation, and our games are part of a larger web of ideas and the grand call-and-response framework of human history. Every game counts, even (and perhaps especially) the “mediocre” ones, because they affirm the medium as a form of expression where you do not have to be “good” to deserve a place, and the (indie) game design community is one where all are welcome. In any case, for those brave souls (or really, souls bursting with stories they cannot contain, and thus must power through into adopting a personal definition of bravery), Anna Anthropy writes, “Whatever you’re doing is right because you’re doing it, and that’s valuable.” De-centering success from financial viability is a place to start.