If you were to ask me for a list of my favorite forms of art before entering this class, I would have replied (in order): literature, visual art, music, and film. Critically, games were absent from what I considered to be art. Games were relegated to the domain of the Internet that specialized in YouTube walkthroughs of Legend of Zelda and Skyrim, embroiled in its own gamer-speak and hyper-fixated on battles and violence that took place in fantasy worlds, inaccessible to outside audiences. You were either a gamer or you were not a gamer. I loved most iPhone simulation games and puzzles, mindless ways to pass time by accumulating artificial goals that took the form of artifacts, free-to-play games who make themselves accessible to newcomers.

This class has exposed me to a wider genre of games through which I have found the beauty in walking simulators and narrative-driven games, particularly through playing “What Remains of Edith Finch.” As a writer interested in storytelling, poetry, and visual art, I found “What Remains of Edith Finch” to be the perfect combination of storytelling through interactive graphics. The questions that drive my writing are the following:

- When does the reader become a participant?

- How do I translate a specific experience to the reader?

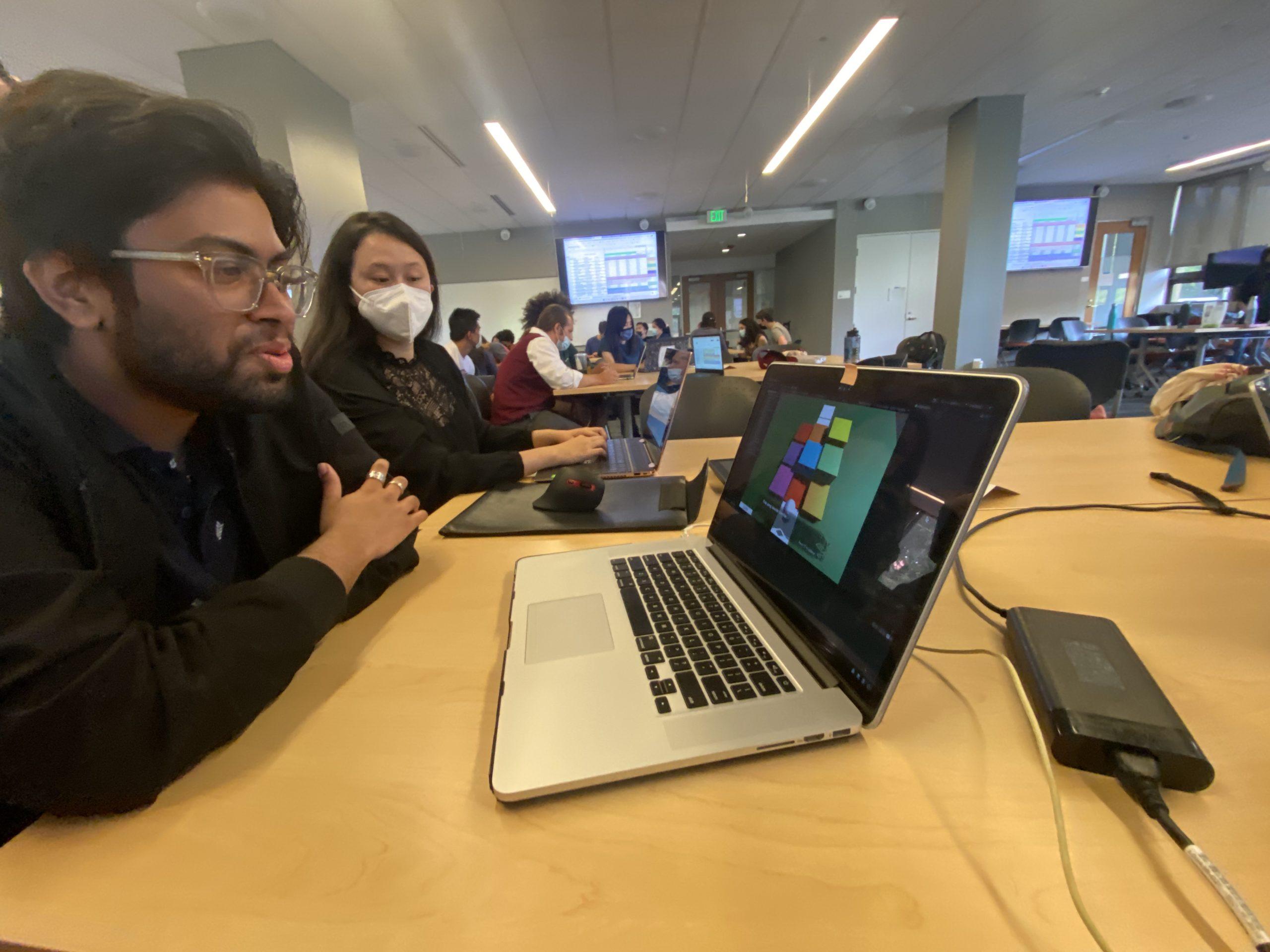

Walking simulators — and games writ large — as a medium force the player to be an active participant in the narrative. The effect is that participants must grapple with moral decisions they have actively made through the game, as in “Life is Strange,” and through the process of decision-making reach a larger understanding of both the story and of humanity. Moreover, walking simulators have pushed back against what constitutes a game. Towards the beginning of this class, we learned what a game is meant to be and what a game is not, which is a mental exercise that engages players and challenges players. The gatekept definitions of a mental exercise as an exercise in tactical strategy (a residual, no doubt, from gaming’s history rooted in the military-industrial complex) where strategy consists of shooting other players, hiding between features of a specific landscape, and making it from point A to point B, I have since learned are only one definition of a game. A mental exercise can also be to grapple with a mystery, or perhaps a puzzle, and to figure out the narrative of a world, to understand the emotional complexities of characters in a built world. I have noticed, through my two groups and through playtesting in class, there is still an all-too-masculine definition of what constitutes a game, where the first-person shooter games specializing in tactical strategies are often built by all-male teams, where women are often responsible for graphics and narratives.

Games are not as freeform as I had imagined, in world-buidling games like “Sims” and “Minecraft,” as we learned in lectures focusing on the architecture of games. Spaces are designed to be explored by players, and the architecture of these spaces allows for players to make certain decisions, and limits players from making other decisions.

The social element to games fascinates me, particularly from Dan Cook’s lecture on building meaningful friendships from games. An important takeaway on the importance of games, is the way that we might connect with one another, better understand one another through decisions we make in games. Through Dan Cook’s lecture, I gained an understanding of games as fundamentally social activity, something that I hope to apply in HCI research (some of the most interesting research I’ve encounted this quarter through CS 347 have been studies of user mental models through games like Tetris). During the pre-vaccination era of COVID-19, the importance of gaming, and particularly digital gaming, was more important than ever as a way of fostering deep, meaningful connections. By incorporating elements of reciprocity, proximity, similarity, and disclosure, we might bring people together without needing to explicitly focus on the cliche questions, as “We’re Not Really Strangers” does. Rather, we can bond and foster deep connections through frequent interactions in spaces designed for deeper connections.

Sketchnoting has drastically freed up the way I write, reinforcing the message that we should take notes in ways that make sense to ourselves, which are not always structured the way lectures are organized. Sketchnoting has freed my notes from tightly confined bullets within a bullet journal to free-form notetaking where I have learned to distill lectures into concepts that make intuitive sense to me, which is the purpose of notetaking.

In designing games, I have learned to appreciate the art form of gaming, opened up my definitions of what constitutes a game, and will play games more critically in the future. This class has been the beginning of my appreciation for games as an art and broadened my horizons for game design.