Our Design Process

Artist Statement:

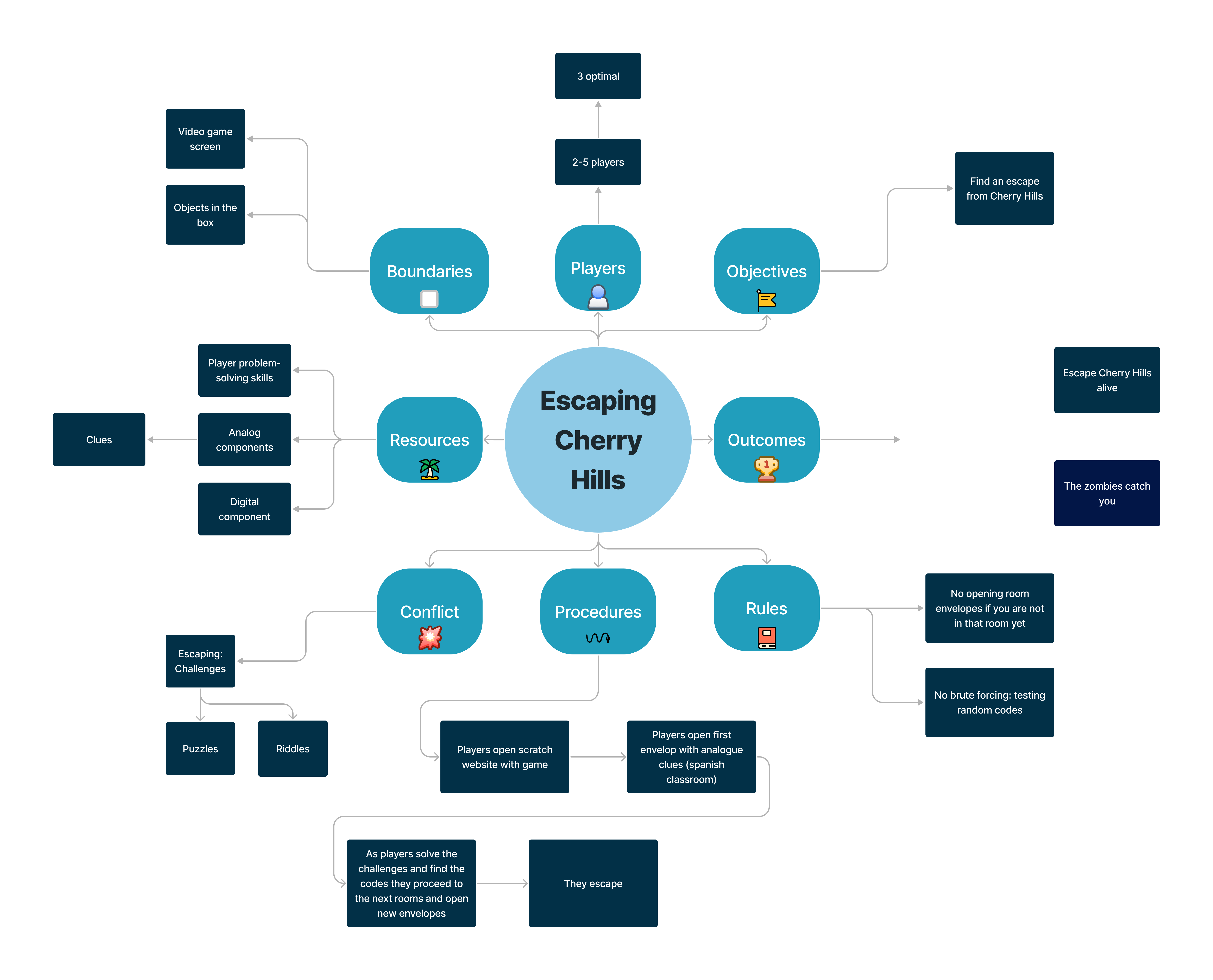

The goal of Escaping Cherry Hills is to create a game that brings people together in an experience that encourages them to think critically and work collaboratively. For this reason, we decided to make an escape room game that has a diverse array of challenges nested within it that requires collaboration.

The setting is a high school in a zombie apocalypse and has a combination of analog and digital elements. The printed materials are in theme with a typical American high school. The digital materials used an 80s, 8-bit arcade theme. These decisions were made to evoke familiarity and nostalgia in players.

Design Decisions

Style and theme are key pieces of our game, because we want to rely on a player’s previous knowledge of pop-culture to evoke a narrative built upon their experiences (our target audience is most likely to have been exposed to media about high schools and zombies).

Using Theme to Further Player Experience

Since our narrative is focused on perpetuating the storyline of a zombie apocalypse attacking a high school is integral to our narrative, we wanted our theme to be sewn into the mechanics of our puzzles. This is reminiscent of the class activity to analyze our theme affects game mechanics in games like World of Goo and Cut The Rope. We appreciated how well the theme of “physics principles” worked with challenges in those games and wanted to recreate the intertwined and symbiotic relationship between theme and mechanics for our puzzles.

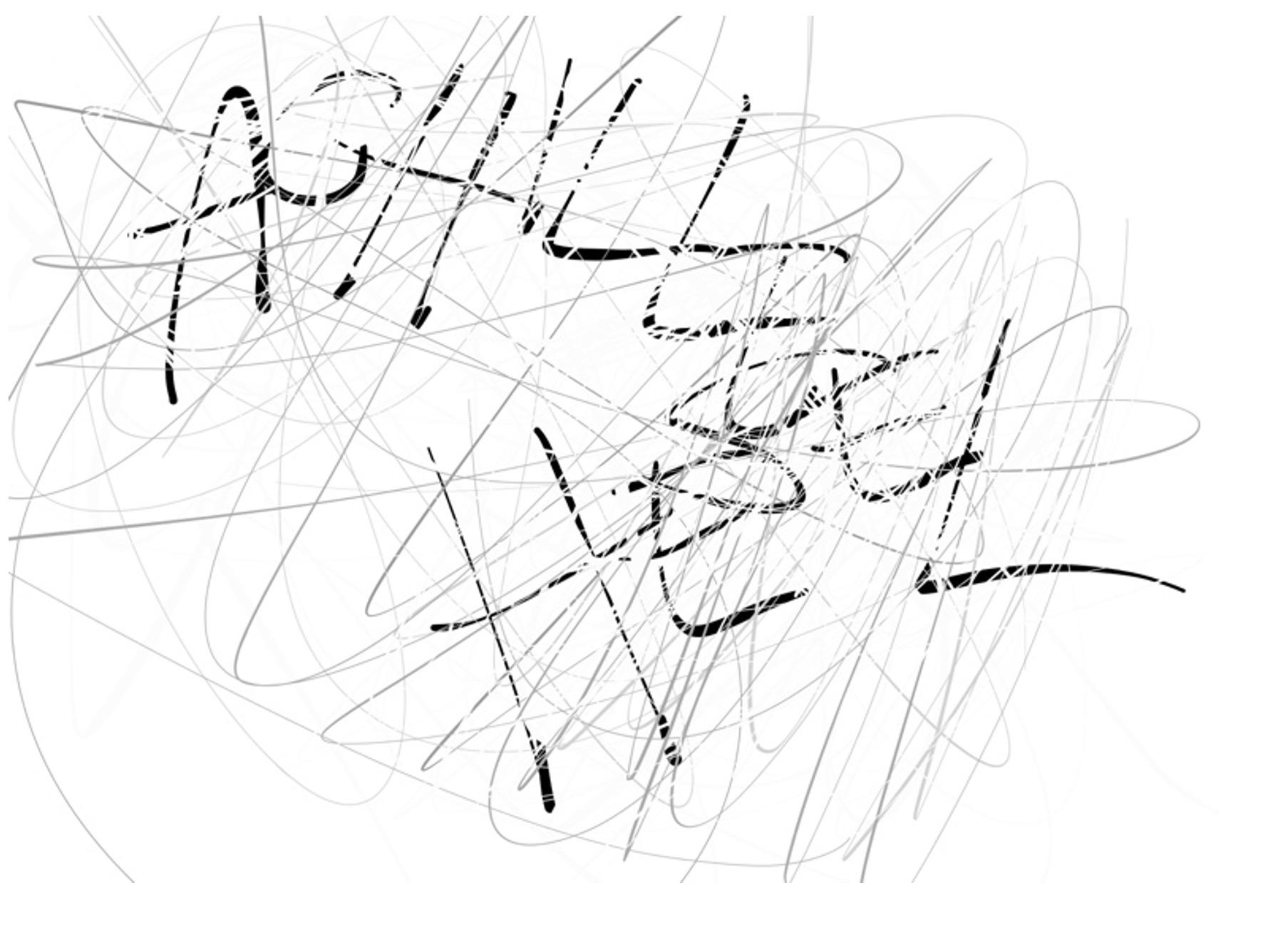

As a result, we used different types of media pertaining to zombies and a typical American high school to activate different types of thinking at various levels of difficulty and harken back to our theme repeatedly throughout the game. One manifestation of our theme in our puzzles is the CAPTCHA puzzle: players had to “prove they are human” to decipher the code.

Secondly, we added the locker room puzzle with the diary to bring players back to the idea that the setting is a high school; students have diaries and random objects in their lockers. It is common that one would need a locker combo to enter a student’s locker, which is the reason we included that aspect as part of the challenge in this room.

Evoking Familiarity

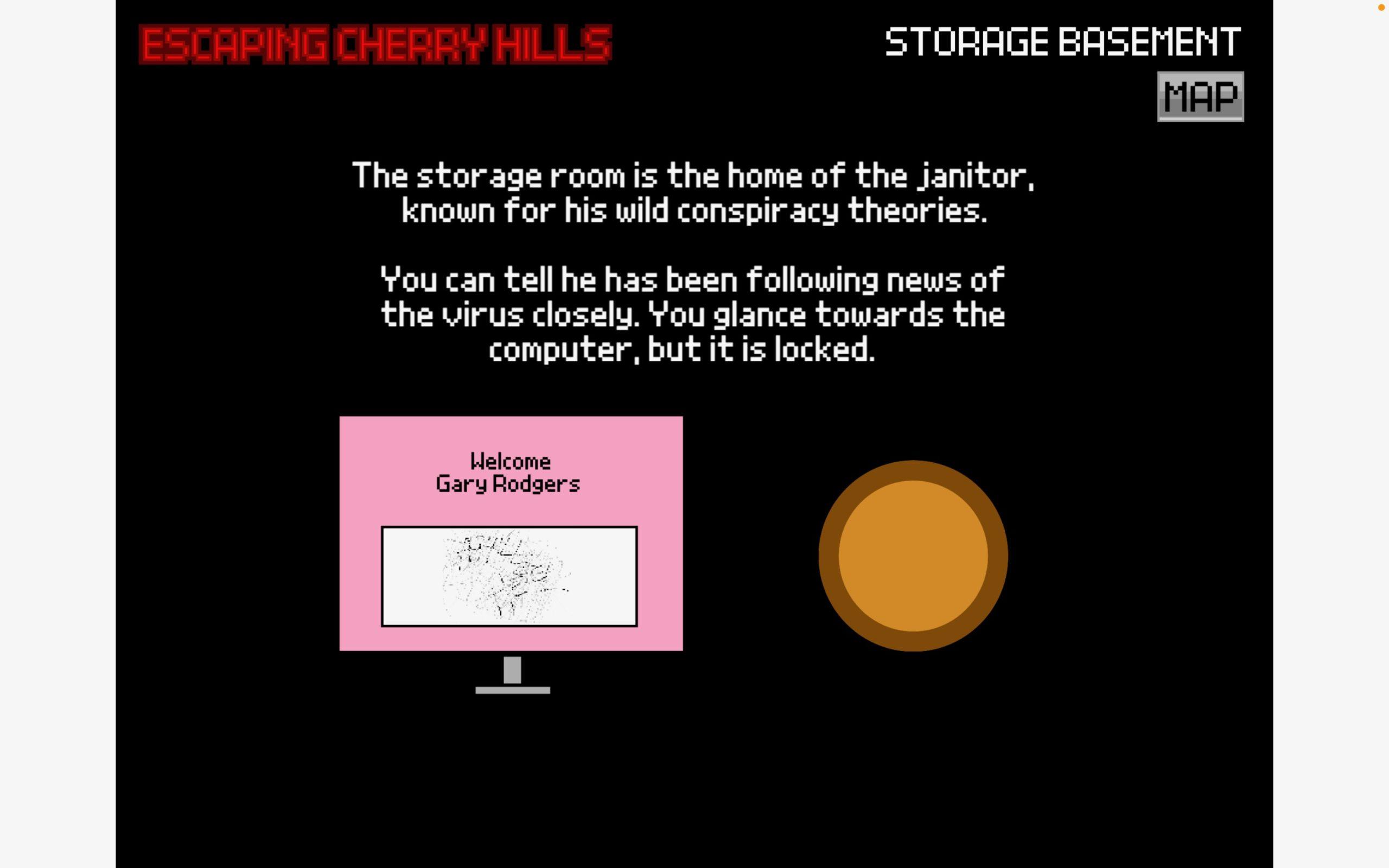

Along the vein of evoking nostalgia for players and using visual elements to trigger a sense of familiarity with our setting, we use pixel art in our digital components. The digital part of the game uses retro arcade imagery in order to create a sense of ‘retro-ness,’ especially since all of us game designers grew up going to schools that did not have high-tech systems (hence the low-quality, pixelated detail) nor did our teachers have robust security systems – it’s normal that someone like Maria Santos would put her dog’s name as her password given our experiences. We wanted to not just make a game that was fun but also had the essence of our shared experiences as game designers and collaborators.

Translating Narrative into Mechanics

We added sound effects but chose to keep these separate from gameplay, making the puzzles playable, enjoyable, and accessible to people who may not be able to hear well. This was intentional so that players would focus on the visuals for solving the puzzles, especially since our game is very focused on players sifting through documents and finding clues like a detective. In addition to sound effects, we implemented an underlying soundtrack that is not essential to gameplay, but we thought it could help contextualize the game in an eerie environment, amplifying the atmosphere we wanted to evoke during gameplay.

If one examines our printed materials, we intentionally added blood splatter, ripped and crumpled pages, crossed X’s on people’s faces to represent those who were ‘lost’ to the zombies, and other elements to recreate what one would find in a high school that has just been besieged by these bloodthirsty foes.

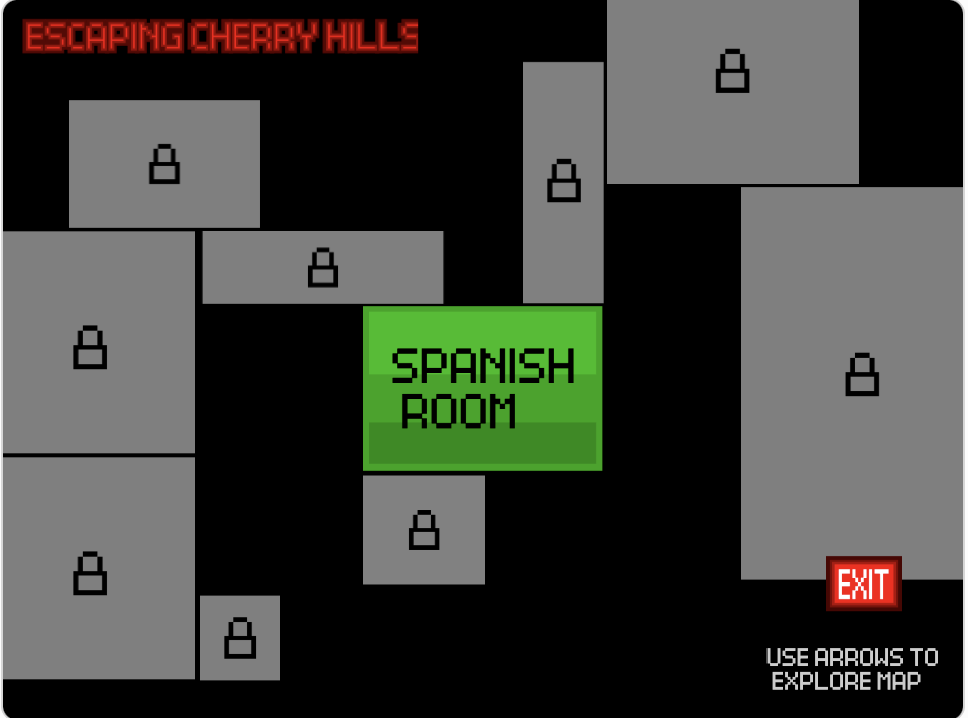

Incorporating Class Lesson

From the course material, we found that explicit tutorials that ‘feel like tutorials’ are not necessarily the best and instead, one should opt for embedded tutorials. Although we did not add a tutorial due to time and technical constraints (due to Scratch being quite cumbersome), we intentionally implemented an interactive map of Cherry Hills High School to help players understand their progress in the game and how the rooms within the game fit together, giving further purpose to our puzzles and an answer as to ‘why’ they are traveling through specific rooms (the path the students take in this slice, if one analyzes the map, is the one that leads to the ‘EXIT’ sign so they can escape).

Bridging Digital & Analog Gaps

As they get closer to escaping the school, evading zombies while solving puzzles along the way, players move through rooms that turn green on the map to indicate progress. To ease the transition between digital and analog, we displayed pixelated graphics on the screen that closely imitated their analog counterparts to create an intuitive flow between components. For example, we show pixelated images of the mazes within the ‘Storage Room’ envelope to hint to players that they should start looking at the maze-related materials to solve the puzzle. See photo below

On the computer screen, notice the pixelated version of the captcha printout to hint that players should look at that

This is the physical document the players have.

There are more examples of the high school and zombie theme manifesting in our design decisions, but these above, we believe, are most salient for demonstrating our intentional design.

Target Audience

To ascertain the target audience for our game, we first referenced the ESRB rating guidelines for interactive software products, particularly games. Since our game is a mixture of digital and analog, we thought this rating system would be appropriate.

According to their rating system breakdown, our game would be considered appropriate for anyone over the age of 12 years old. Our game lacks expletives, suggestive themes, gambling, and crude humor, all of which would warrant a ‘Teen’ rating of some kind. However, our game does include insinuations of violence, some blood (spattered on the materials), and a theme (a zombie apocalypse where humans are being eliminated) that could scare children, all of which made us reluctant to indicate this game is for anyone over 10 years old. Therefore, we made a compromise and selected 12 years old as our minimum age suggestion. Furthermore, our game is based on the theme of a school being ravaged by a zombie apocalypse; players who have a more robust sense of a school, particularly a high school, which would be older children, would particularly find this game relatable and easy to understand.

Core Concepts, Main Design Elements

Using the knowledge we learned in class, we focused on several teachings when designing our game that we thought could not only improve the game’s flow but also help players feel more satisfied when playing, especially since burnout seems so likely when speaking about puzzles that could be of varying levels of difficulty and required skill levels,

Game Architecture

One learning from the course that we found incredibly relevant was the lesson ‘Game Architecture.’ We focused on including interaction loops and interaction arcs to help players become more familiar with the game as they played.

- Interaction Loops

- The initial puzzle gets players used to how our game works: search materials and type in code.

- The loop of searching materials and typing becomes normal as players continuously play the game highlighting the key concept of “mastery through repetition”

- Interaction Arc

- For the interaction arc, feedback is critical

- In our game, we intentionally let the player know they are correct or incorrect upon the entry of their input.

The main core loop throughout the game is that players enter a room, look for hints and clues, and solve a progression of puzzles in order to unlock the next room. This was kept standard throughout the rooms, although the types, difficulties, and amounts of puzzles changed from room to room. We wanted to create puzzles that would challenge the players without getting repetitive, while also reinforcing the core loop of what they needed to do to progress in the game.

Narrative Architecture

From the lesson on narrative architecture, we leaned into the style of using evocative spaces to help us build a connection between the setting and the puzzles: we thought that by using players’ existing familiarity with our theme and media associated with our theme, they could use intuition to solve puzzles in addition to the materials offered.

- Evocative Spaces

- Although players have clearly not had high school experiences where zombies attack, we knew that most players would have familiarity with this genre of sci-fi, apocalypse-type media.

- We leaned on that assumption of familiarity because it would make the game feel more intuitive and easier for players to lose their sense of reality when playing.

- Secondly, we involved the arc of a high school being attacked, because there are several forms of media that involve this topic of high schoolers facing adversaries and striving hard to escape; one key example being the Netflix show All of Us are Dead.

- We wanted to use players’ experiences in high schools to bridge the gap between figuring out what to do based on what the game tells them and figuring out what to do based on intuition.

- If players understand the mechanics of a high school, they would understand where to look for clues in our game i.e. if one is in the library, there would typically be library cards; if one is in a classroom, teachers typically have memorabilia of their loved ones somewhere in the class – in our case, in Maria Santos’ folder.

Formal Elements of Game Design

- Players

- Players-vs-game

- Given the premise of our game, it is clear that the most fundamental player relationship is the one between the players and the game that continuously presents them with challenges.

- We intended for players to interact with each other as teammates, not as competitors; this is exemplified by the storyline in which the players are all high schoolers trying to escape

- We intentionally did not include individual scores or individual identities per player to prevent the idea of tribalism and rise of players caring more about personal success over team success.

- We strengthen this relationship by pushing the players to cooperate to face their joined obstacle, instilling camaraderie and cooperation through the puzzles that require everyone’s mind at work to solve them.

- Player-to-character

- We focused on creating a player-to-character relationship through the narrative of the game: players become familiar with characters as they get more familiar with the idea that they are high school students stuck in the school in the midst of a zombie apocalypse.

- For example, Maria Santos and Gary Rodgers are characters whose personalities or lives influence the puzzles and the narrative.

- This helps reiterate the theme and exert the theme’s influence on the game’s mechanics.

- We focused on creating a player-to-character relationship through the narrative of the game: players become familiar with characters as they get more familiar with the idea that they are high school students stuck in the school in the midst of a zombie apocalypse.

- Players-vs-game

- Objectives

- ‘What is the object of the game? What are players trying to do?’

- In our game, we answered these questions by making the goal explicit in our storyline sequences that the players must get to the ‘Exit’ in the school map to survive the zombie apocalypse.

- We indicate that to get to the exit, the players must solve the puzzles that lock the doors which lead to the exit.

- ‘What is the object of the game? What are players trying to do?’

- Resources

- What kinds of resources do players control? How are these manipulated during play?

- For resources, we offer the analog and digital components for the players to manipulate at their own will. The envelopes in our game kit are not locked, are clearly marked for the specific rooms they will encounter, and it is up to them to figure out how they want to use these resources.

- However, as mentioned above, we do offer a hint through the pixelated images of printed materials (i.e. a pixelated diary on the game) that players should use specific resources for specific puzzles.

- What kinds of resources do players control? How are these manipulated during play?

- Boundaries

- For boundaries, we wanted to make it clear that the game existed within this ‘Magic Circle’ where players do not need to leave this version of reality.

- For that reason, we abstain from including any materials that would cause players to interact with materials that represent ‘our reality’ such as news about current events in this time or pop-culture references that are particularly relevant to this time period.

- Note: We include a Stephen King reference, but we believed this would not violate the magic circle since the Stephen King magazine cover is from decades ago and acts more as a reference to his novel rather than any current events involving him.

- Rules

- Our main rule in this game is that players cannot progress to new rooms until they solve the puzzles in existing rooms. This restricts player progress and pushes them to follow the game’s intended pathway.

- Procedures

- For procedures, we focused on the ‘progression of action’ as a result of our rule.

- As players solve puzzles, they open new rooms, confront new obstacles, resolve new sources of conflict, and get closer to their main objective

- For procedures, we focused on the ‘progression of action’ as a result of our rule.

- Conflict

- Conflict usually arises as players are on their quest to complete an objective.

- In this game, the objective is to escape the school.

- Hence, the puzzles act as the main source of conflict players must overcome to achieve their goal.

Cursed Problems

We utilized the lessons learned from the ‘Cursed Problems’ lesson to help us fight the emergence of the ‘Quarterbacking Problem’ which plagues many games focused on cooperation as the basis for player relationships. Given that our game wants players to cooperate, and players would aslo like to cooperate (given that escape rooms usually are social, cooperative activities), we had to figure out how to fight the rise in centralized decision making. Although we interacted with this lesson late in game development (in Week 10) and would most likely make changes to previous changes if given the chance now, we made specific design decisions to push people to work together to solve the puzzles rather than have one person do them:

- The mazes in the storage room

- There are four mazes which we hoped that each player would attempt to solve and then put their findings together to figure out the answer. If one person were to do this, it would be exhaustive to fill out four mazes and decipher a corresponding riddle.

- Therefore, our goal in designing this room was not to make it impossible to solve alone, but rather ‘easier’ to solve cooperatively, fighting the urge for a single player to take on all the responsibility of solving the entire room.

- The locker room

- In the locker room, we include two major sets of materials that pertain to the two challenges, the locker combo and the toolbox combo.

- We created the materials so that players would have to split up and analyze the yearbook and the diary entries simultaneously to solve this.

- If one were to try to do this oneself, one would become completely exhausted with reading all the materials and shuffling through the papers.

Our goal with combatting the cursed problems is a manifestation of ‘Occam’s razor’ where we made the game so that it is far simpler to work together than to take on the challenges alone.

Tone

As mentioned above in the analysis of our design decisions, the tone of the Escaping Cherry Hills is meant to evoke a dark, ominous, suspenseful, foreboding, and tense atmosphere. We aimed to achieve this through the setting of the story being in a zombie apocalypse in a high school. The development of this setting, a ‘time-of-crisis’ , continues with the implications that the background characters, the players’ peers, have been turned into zombies (as seen by the Xs on their faces in the yearbook).

Moreover, we center the challenges around the objective of ‘escape’ and use this word intentionally to evoke its connotation as a concept when one is evading danger; the students’ lives are in peril, and they need to outsmart the zombies and get to safe spaces on their quest to leave the school and survive out in the world. By using escape as our driving motivation for players, we hoped it would introduce the urgency and tension we wanted to embed in the game. We magnified this sense of urgency through indicating the need to solve puzzles to leave the school amidst zombies trying to locate and ostenbily eat/kill/convert the players; if one were in this situation, they would want to leave the school to survive as soon as possible.

Model Map

Playtesting & Iteration History

Playtest #1

Objective: During this initial playtest in class, our goals were to test several mechanics relating to our puzzles to help orient ourselves in how to design a satisfying escape room that utilizes both digital and analog components.

The specific questions we wanted to answer included:

- How were our initial puzzles received in terms of difficulty level?

- How did our puzzles fit into the storyline we established for the game?

- How could we optimize the flow between digital and analog given the current status of our materials in both categories (the printables and the Scratch game)?

- How could we ensure all players work collaboratively and do our current puzzles achieve this?

Participants & Process

For our first playtest that occurred in class, the participants were students who all did not know each other, so this was ideal for seeing if strangers could come together as a team through our game. We had a total of three players, one of our team members was moderator, and another team member facilitated note taking.

For each playtest instance, we had the teams play the entirety of the game in its current status at that time. After each playtest, we would ask the teams for feedback and pose questions related to the ones above to gain insight into how to improve without interjecting our own beliefs and biasing our progress.

Feedback: What Went Well…What Didn’t:

What Went Well: One of the key points of tension we had initially was that we as new game designers were not confident in our abilities to design puzzles that people would even enjoy. However, from the remarks of our playtesters, they enjoyed how the puzzles were not riddles but rather investigative, lowering the stress on their brains and pressure for them to ‘perform’ in front of us. Secondly, they enjoyed the materials we had brought to them, with the To-Do listing out relevant information to the Spanish room; their smiles and ‘oh’s coupled with their explicit appreciation for the printables indicated that they liked playing ‘detective’ with our game. This ‘detective’ style also pushed players to work together, and we observed significant amounts of conversation between the players where they were asking for each other’s opinion and ideas to solve the puzzles. We did not observe a single player dominating the decision making process.

Furthemore, we were worried our game would be too quick since the puzzles were not too difficult, however the team spent 12 minutes for the entire playtest which was ideal; we had not implemented all the rooms at this point, so that timing seemed appropriate given we had two rooms (two puzzles) developed.

Lastly, given that our narrative sequences were not fully fleshed out, we were not able to get an accurate assessment of how well our puzzles fit into the storyline, but the players indinciated, upon questioning, that they didn’t feel like the puzzles were ‘out of place’ and ‘made sense.’ This indicated that our goal of evoking familiarity within players and their own high school experiences and knowledge of zombie media seemed to be effective.

What Didn’t Go Well:

Primarily, we observed that our players were not significantly stimulated or challenged by our puzzles. Specifically, the Spanish room puzzle and Library room puzzle were not as challenging as we would have liked since the players indicated no struggle or lulls in an activity where they would be thinking. Instead, they quickly found the answer to the Spanish with one look at the To-Do list that listed the teacher’s dog’s name four times. They then swiftly solved the library puzzle by noticing that some of our library cards were labeled ‘ME.’ This immediately drew their attention to those cards and the players ignored the first part of the puzzle where they had to put together the Stephen King puzzle.

Secondly, we observed that our digital component had several bugs which caused pauses in gameplay and the need for intervention from one of our team members to resolve. This disrupted the flow of the game and interrupted the players’ suspension of reality.

Changes We Made (after hearing feedback from the playtesters):

To address the issues with the Spanish room, we reduced the clues we offered to something less overt: we had initially referenced the dog’s name “fluffy” four times in the To-Do List in Maria Santos’ folder, and no other names were present, making it obvious that this was the solution. Our change was that we introduced a new name referenced in Maria Santos’ documents, a student’s name, and reduced the number of references to her dog to one instance. To prevent unnecessary ambiguity between the dog’s name and the student’s name, we also included photos of the dog inside the teacher’s folder; this also acted as a way to highlight the dog’s importance and thereby its name over the student’s name.

To address issues with the library room, we changed the clues present so that the players had to interact with 100% of the materials to some extent to solve the puzzle. We removed references to the person who checked out a book as ‘ME’ and replaced them with instances of the librarian checking out the Stephen King novels. We made this change intuitively because it would push the players to utilize more game materials: they could either do what we intended, solving the first puzzle, the ripped Stephen King magazine, which would lead them to the specific library cards, or they could analyze the school directory and piece together who checked out the book and when.

The next thing we improved in this version was adding a final room (storage room) to extend total play time and incorporate new types of fun (new challenges with more difficulty).

Type of Fun

Given the players’ feedback, we believed at this time that we were on track to achieve a game that evoked the “challenge” type of fun since the players already enjoyed the puzzles even without significantly tweaking them. Additionally, given their intense amount of conversation, laughing, and using each other’s strengths in critical thinking to solve the puzzle, we believed that our game sufficiently created a “fellowship” type of fun for players. However, we were not able to conclusively decide that our game evoked a successful form of “narrative” fun at this point.

Playtest #2:

Objective: During this playtest, our primary questions were:

- How were our updated puzzles received in terms of difficulty?

- How did players feel during the game? Was there burnout?

- How disruptive was the increased difficulty of the last room?

- How did our narrative and the puzzles fit together? Did they seem cohesive?

- Were our updated printables sufficient and intuitive for solving the puzzles?

Participants & Process

During this second playtest, we recruited three new players and two of our team members, one a moderator and the other a note taker.

Feedback: What Went Well…What Didn’t

What Went Well:

Primarily, our playtesters indicated that they felt the difficulty of the puzzles was appropriate, and they were not exhausting to solve. Secondly, they indicated that they did not feel burnout, but rather felt continuously stimulated by the puzzles, especially remarking that working with the digital component, the Scratch game, was ‘cool’ and surprisingly highly developed. They also indicated that the mazes pushed them to work together, highlighting an improvement in the aspect of collaboration that we hoped for. The players also indicated that the printables were adequately related to the puzzles and sufficient for solving the challenges that required them. Lastly, no sense of burnout or exhaustion was reported or indicated by playtesters.

What Didn’t Go Well:

The players indicated that there were a lot of printables and they were not as organized as they would have liked. They indicated that they were a bit stressed that they had lost a crucial piece of printed material to solve the puzzles through all the shuffling of documents.

Moreover, one student mentioned that the storage room having BTS references as clues to solving the puzzles in this room interrupted their suspension of reality. They indicated that it didn’t make sense for Gary Rodgers, our fictional character who set up the puzzles for the storage room, to be a cleaning-services employee and then randomly a huge BTS fan. This note was particularly important given we wanted to improve our narrative’s cohesion with the puzzles: the BTS references were not consistent with the theme of an American highschool in a zombie apocalypse.

Changes We Made

Our first major change was eliminating all BTS references from the storage room and replacing the narrative of Gary Rodgers, the BTS fan, with the narrative that Gary Rodgers had found the ‘secret weakness’ to beating the zombies; the challenges in this room were then changed to highlight this narrative arc.

Secondly, we made a concerted effort to organize our printables, consulting with Eugene, Jean, and Khuyen on how best to compartmentalize our materials without sacrificing some of the fun of being a ‘detective on the hunt for clues.’ After hearing their feedback, we decided to staple or connect relevant papers together and group materials per room in envelopes to help players easily find printables for corresponding rooms without losing them.

Type of Fun

Given the players’ feedback, we were relatively confident that our game offered the “challenge” and “fellowship” types of fun with all players actively collaborating to figure out the puzzles, especially when the puzzles increased in difficulty. They were talking to each other and saying things like: “Hey you do this part, I’ll do this part…Hey, do you think the answer could be this, because….?” Additionally, we believed that given the further development of our digital component and printables, our offered “narrative” fun improved but still needed more work to seem cohesive with our puzzles.

Playtest #3:

Objective: During this playtest, our primary questions were:

- How were our updated puzzles received in terms of difficulty?

- How did players feel about the printables?

- How well did the narrative fit in with the puzzles?

- How were the updated puzzles perceived by the players?

Participants & Process

During this third playtest, we recruited four new players and two of our team members.

Feedback: What Went Well…What Didn’t

What Went Well:

Similarly to the previous playtest, the playtesters enjoyed the difficulty of the puzzles and the overall time spent on our escape room increased (25 minutes). They particularly enjoyed the maze puzzles, and we observed the highest level of collaboration during this portion of the game. The players also enjoyed working with the digital component and newly organized printables. Our playtesters also remarked that they felt the thrill of having to ‘escape the zombies’ in the first room.

What Didn’t Go Well:

Primarily, the players remarked that they didn’t feel a sense of urgency by the end of the game to escape zombies; they had forgotten about the zombie aspect. The players also indicated that they were confused as to which clues corresponded to which room (note: this playtest was on the same day as playtest #2, so we did not have a chance to incorporate the envelopes in this playtest). The players also seemed to be hacking our Scratch, brute forcing answers through guessing combinations rather than thinking critically about why, for example, 2358 would be ordered in such a way if it’s a time (23:58 is the only way a measure of time could be represented); instead they just typed in 2538, 4258, 8352, etc. until they got it.

Changes We Made:

As mentioned earlier, we focused on organizing the printables for our final game by incorporating labeled envelopes to compartmentalize the clues. Moreover, we added more storyline sequences throughout the game to consistently remind players that zombies were around them, and they needed to escape. At this point, we could not manipulate the Scratch to incorporate “limited number of guesses” as a mechanic, but we mention that this would be a definite improvement if we kept working on this game.

Type of Fun

This version of the game, the current version, seems to offer adequate amounts of “fellowship” and “challenge” types of fun given our feedback. Despite the weakness in our narrative sequences, we believe that our current game also offers an improved level of narrative fun, but could definitely be improved.

Playtest #4: Khuyen – Post-Mortem

We played the game with Khuyen and below are our takeaways from this playtest that can illuminate more details about our current game status and how we can improve it.

One of the biggest issues we discussed together is that we were technically limited in our digital component of the game. At one point, we were going to code our digital portion in JavaScript or Unity, however we had already started with Scratch and developed the game ot a point that we faced a sunk-cost issue where it would be infinitely harder under our time constraints to devise a new technical component that was robust and bug-free. In the future, we would definitely use a different game engine for development.

Secondly, we collectively recognized that our game lacks purpose in why puzzles are there, which is what significantly hampers the storyline. For example, why would one need to put together a Stephen King puzzle to open a door to the storage room? One glaring improvement we can make to enhance our storyline’s cohesion with the puzzles is present background information on why these puzzles are important for escaping or present information on why a character in the game would be creating these puzzles and how the solutions to them contribute to the storyline.

Thirdly, Khuyen highlighted a key lack of consistency in how our game presented information to the players: in the Spanish room, one must analyze all the information present to figure out the answer. However, in other rooms, for example, the locker room, we are potentially confusing the players by presenting a lot of information in ways such as the school directory, and not indicating what is important for solving the puzzle. This leaves players confused about to what level they should be analyzing the printables per room, since one room requires complete analysis and another requires a quick gloss over the directory.

Lastly, we discussed the jarring jump in difficulty with our last room, the Storage room and its puzzles. Ideally, we would have split up those puzzles into separate rooms, but due to time and personnel constraints, we thought it would be best to include more challenging puzzles and extend the time for our game than to omit them entirely. Our vision was that our puzzles would increase in difficulty and that the last room should be much more difficult than the first room, but we think we might have overshot that.

Future Directions:

The first development our team would like to implement is a timer throughout the game to add pressure to the players’ experience, forcing them to be quick on their feet without having them burn out. To do so, we would add a countdown timer to the whole game that changes in total duration depending on desired level of difficulty. Secondly, we want to implement a limited number of total guesses per room or number of lives for the whole game to limit the risk of brute force and push players to be more thoughtful in solving the puzzles. Lastly, we want to add different puzzle-pathways with increasing levels of difficulty so players can select a more tailored experience.

Final Playtest Feedback

Tomas Di Felice

For the first round of playtesting, I switched spots with Dilan and play-tested “Secrets of Stanford”. This was a digital + analog mystery “escape room” with a narrative based on Stanford’s history. For the slice, they had finalized one of the main puzzles, which involved finding out how Jane Stanford was killed. In terms of players, the game is a “Cooperative game” as I was working with my classmates to solve the mystery. The types of fun intended for this game are “Challenge” and “ Narrative”. The challenge came from piecing together the puzzles and riddles and discovering how Jane Stanford was murdered. For narrative, the game focused heavily on the history of the Stanford family by using analog clues that were both historical (ex: family tree) and evocative (parts of the pages were burned and stained with coffee).

In terms of gameplay, we were able to solve the puzzle in about 10 minutes. I really liked how we had to use several analog components to find the hidden word. I would have wished the digital component was a bit more integrated since all we had to use it for was inputting the word. I enjoyed playing the game and think the “narrative” type of fun was definitely achieved. By reading the printables, and exploring the family tree, I really learned about Stanford’s history. In terms of challenge, this could be because it was just a slice, but I would have wished for more variety.

For the following playtests, I was the notetaker for my team’s game “Escaping Cherry Hills”. This was the first playtest I was present for ( I was playtesting for the other ones), so everything I had heard about how the game went was from my teammates. Overall the playtest went really, well. It lasted 25 minutes for the four rooms. One of the biggest issues players noted was the lack of storyline. While they enjoyed and felt the zombie narrative present at the beginning, they felt that it lost presence, especially towards the end. Also, they felt that the BTS references for the storage room didn’t make a lot of sense so this was definitely something we had to work on. Another big takeaway was that players weren’t sure what analog clues to follow for each room. We, therefore, decided to put everything into separate envelopes.

Nicole Salazar

For the first round of playtesting I played Soort. The game graphics were in 8-bit style and channel traditional side quest game styles. The premise is that I had to sort the trash before my RA checked my room. The premise was fun and so was the gaming in the sense it used challenge as a form of fun. However the specific mechanics were a bit difficult. There was a screen at the beginning with game instructions however the usage of using the buttons for pick up and drop the trash were a bit finicky and unintuitive. I was frustrated because they sometimes would work and other times would not

For the second round of playtesting, I played Sky Chaser. This game did not have an overt onboarding process. However, it was intuitive because it used the arrow keys and space bar to navigate the avatar. It relied on my previous gaming knowledge. Additionally, the goal was really easy to see because there was an easily accessible star to catch and one of the bars lit up after I caught it so I knew I was supposed to catch all the stars.

Dilan Nana

For the first round of playtesting, I went to play the game, Escape From Your Mind. The premise of the game is to go through puzzles that are EBF-themed to help a student escape. The game consisted of a riddle/puzzle where we had to figure out the combination to a lock based on the times displayed on clocks. The second puzzle involved moving a magnet through a maze to retrieve a key locked inside it. The third puzzle involved solving a logic riddle where we had to figure out which characters were associated with which shadow emotions like grief and anxiety.

The formal elements of the game mainly included players, outcomes, and resources. This game focused on being players vs game which manifested in how the other playtesters and I had to work together to solve the puzzles since they were quite challenging. One example is the first puzzle, I could not figure out, but with the input of the two playtesters, we cracked up an idea that ‘what if the times are actually numbers that we need to sum to figure out the code.’ The outcome element of this game is critical because the puzzles have solutions that rely on each other; to access the maze and subsequently the logic puzzle, we had to open the lock. Thirdly, resources were crucial to game development; in some games, you can solve the puzzles without analyzing at the provided materials; however, in this game, to answer any of the puzzles, one must examine the clock riddle or the maze or the logic puzzle to open the next level, meaning it was critical to success that we used the resources the game designers gave us.

For the subsequent playtests, since I was the designer of the storage room puzzle and most of the printables for the game, I stayed to monitor game play and handle note taking and feedback. I notified Khuyen about this development as well.

Graciela Smet

For all rounds of playtesting, I was in charge of moderating our own game’s playtest. Since I was the main developer of the software component of the game, I was the only one able to debug the digital components if they glitched mid-game. Developing these digital components also meant that I had a very high-level view of the game and knew the answers to every puzzle in every room, which was helpful in ensuring that users were on the right track throughout the playtest.

Labib Tazwar Rahman

I was present in all but one round of playtesting of our game for video-recording purposes and for helping Dilan with drawing the mazes for the storage room puzzle.

The game I playtested was Ma Nasa/”Weird Place”. I was able to experience their first puzzle as their finalized slice during this playtest. It was a digital + analog escape room that had really focused on immersion—which was emphasized in the game’s design. The digital component provided the story and then we were given one paper with an assortment of symbols and sentences and another paper with some fill in the blanks. The language of the story was piqued my interest and the use of symbols made it a very engaging experience. Going back and forth between the components was a fundamental part of finding the words to fill in the blanks, making this part quite immersive. The hints, which were nice but not really necessary, were initially locked and then unlocked after every few minutes. The user interface was also gave off a weird place vibe which was coherent with the nature of the puzzle. I really enjoyed this playtesting experience and so if I had to provide any feedback I would want the ability to go back to previous hint once other hints open up. Although this game is supposed to be weird, It would perhaps be helpful to get any indication if our way of solving the banks was correct as our validation was done not by the game but by the game developers. Lastly, it would be nice to have a thematic meaning that tied all the components beyond their weirdness. The plot, although well-done, came so early in the game that it could not be recalled easily.

Minecraft Prison Break, the other game for which I was listed as a playtester, already had enough players and so a TA had encouraged me to for support my team instead, and so I recorded our game’s playtesting videos and helped with the remaining puzzles.

Extra Credit

Inspiration

Although our game was not derivative of other games (for example, if we had done UNO but with character cards), we are grateful to have experienced the following games which served as inspiration in various moments of our design process:

Game:

Hunt A Killer’s “Camp Calamity” — Introducing Bradley Brooks as Superkid: It was helpful for us to be aware of the user interfaces of the digital components of these escape rooms like ours while playing this game, especially the computer display behind a passcode. This game showed us how we can use analog components—even if it is just paper—in varied ways to have different effects on the gameplay. For example, this game has papers of different colors, sizes, transparency, and texture (a crumpled page was also there), which all served as inspirations for us to vary the paper-based elements of our game to elicit different emotions and challenges.

How we made ours different/better:

Although this game is a bit different from ours, we thought that it would be better for us to not overwhelm the user by giving them all clues at once. Instead, we compartmentalized our clues by room as we found through our playtesting that dumping all clues at once generally increases difficulty but significantly decreases gaming enjoyment.

Game:

We really enjoyed the gameplay and collaborative nature of the “We Were Here.” It relied on at least two parties working collaboratively to be able to go through the challenges. Although it was entirely digital, we wanted to incorporate game play that would foster player-to-player relationships and build trust and strength among the players.

How we made ours different/better:

We made ours different by allowing players to see each other’s problem-solving and work on the same puzzle. Their game only let one person see the answer and another person had to solve the game.

Game:

We drew inspiration from how Sailor’s Dream draws upon the player to piece the storyline together based on where they went, highlighting its abstract and beautiful narration.

How we made ours better:

We made ours follow a chronological order, included puzzles, and allowed the game to be solved without waiting for certain availability to unlock the next step.

Game:

We drew from the progressive narrative format of Dear Esther. Using this idea, we introduced our storyline as users completed levels so that the user’s motivations are more aligned with the progression of the game. We also learned that having a balance of withholding and revealing information, instead of dumping the plot at the start of the game, perhaps also added another layer of intrinsic motivation for the players by tapping into their desire to know what happens next from a narrative perspective.

How we made ours different/better:

Although we liked the dark theme of this game, which we also embedded in our Scratch by making the background black, unlike Dear Esther, we used more contrasting colors so that it was easier to visually comprehend the game and to improve the accessibility of vision.

Accessibility

We tried to make sure every component of our game is accessible to individuals with color vision deficiency (CVD) using a two-fold approach: 1) eliminating the need to rely on color differences to play the game, and 2) testing all visual components to make sure it is accessible to people with CVD anyway. For our digital component, we used a Chrome extension with Scratch to check for CVD accessibility. And for our analog parts, which were primarily designed on Figma, we used a Figma extension.

To make our game’s digital component accessible to the deaf and hard of hearing community, we made our game sound-optional i.e. having sound is not needed for gameplay.

Takeaways

DEI-focused (as illustrated in our choice of names). We also very intentionally made our game in a way so that it does not have any exclusive American cultural references so that it is playable by people from other cultures too. We ensured this by various iterations as we did not have these focuses in our initial versions of the game.

Walkthrough of our game:

https://www.dropbox.com/s/y9ov9il6k9n4l91/Walkthrough%20-%20Escape%20Cherry%20Hills%20-%20.mp4?dl=0

Please visit this link – if it does not work, please email dilan99@stanford.edu

Gameplay Video:

Scratch Link:

https://scratch.mit.edu/projects/685958813