Artist’s Statement

We were all initially brought together by our love for social deduction games. Spyfall, Mafia, Secret Hitler – all of these games involve a combination of strategy, bluffing, trust, and betrayal. We wanted to create a game that also incorporated fun through fellowship, challenge, and a little bit of roleplay!

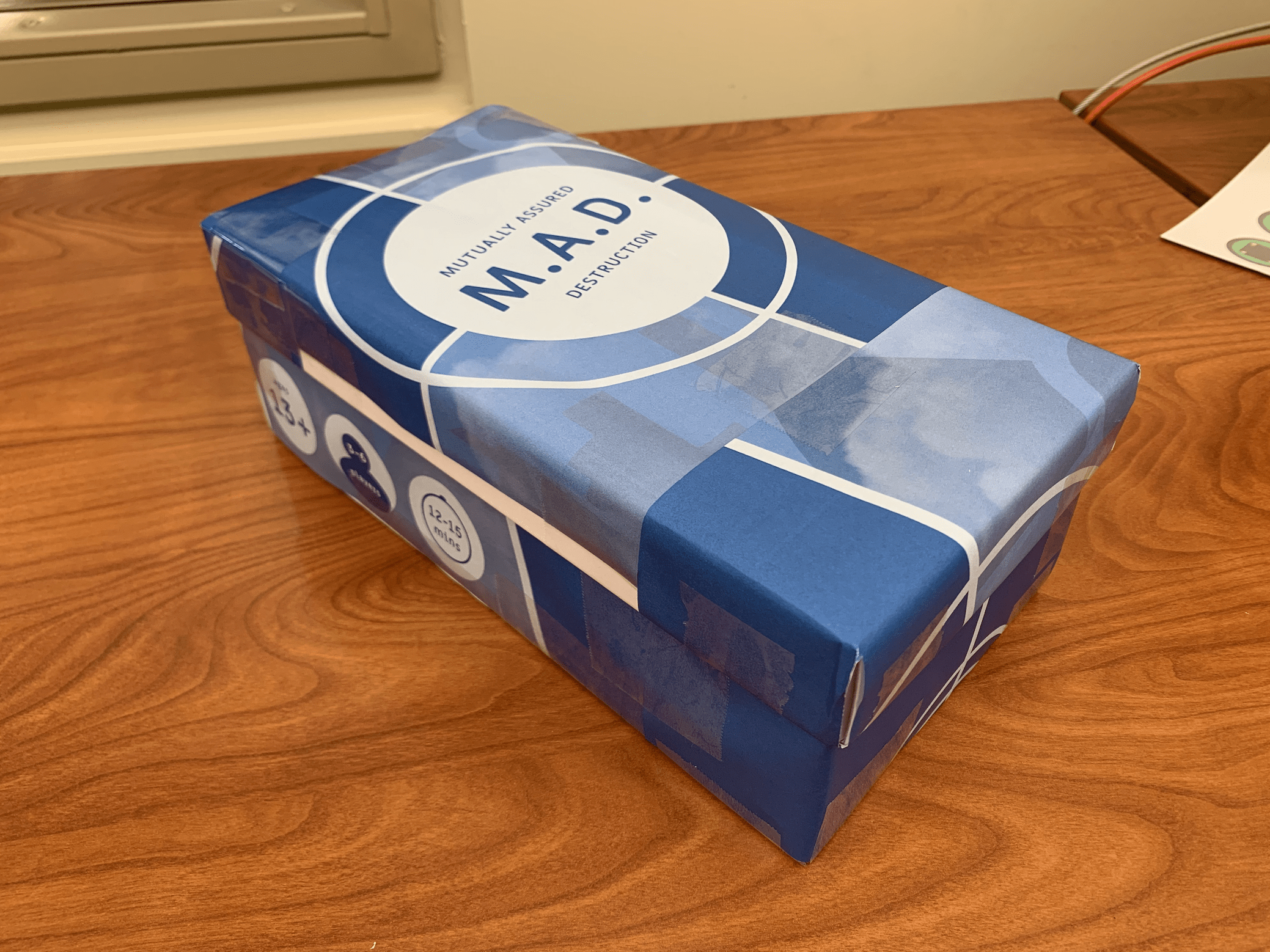

One thing we noticed in many games like Mafia is the fact that there is only a binary outcome: you either win, or you lose. We wanted to augment this idea to provide more of a challenge, but also to better mimic decision-making in the real world. We based our game, Mutually Assured Destruction, off of game theory: a concept that has implications in biology, economics, and nuclear warfare. Based on different patterns of cooperation and betrayal, there are different outcomes that lie on a spectrum of most to least optimal. Two people can win one time, and everyone can lose another time!

We wanted to make sure that our game wouldn’t lose its fun even after multiple plays. Through several play tests and iterations, we discovered an optimal way to distribute resources to each player that could result in a variety of different strategies. Through the variability of human psychology as well, we hope our game provides a challenging, but fun way to create and break trust amongst players.

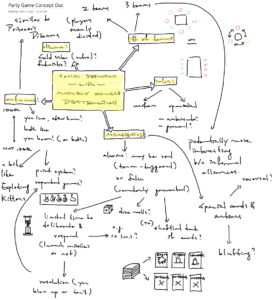

Concept Map

Initial Decisions

Formal Elements

From a technical perspective, we wanted a social game featuring lots of engaging conversation and player-influenced outcomes. From a fantasy perspective, we wanted to create a tense, confrontational atmosphere inspired by the Cold War era nuclear standoff. We intended for the formal elements to reflect these aims.

- Players: MAD fields 3 to 6 players engaged in multilateral competition.

- Objectives: Objectives are somewhat player-dependent, but almost always involve a combination of outwitting other players (aggressive play style) and finding solutions (cooperative play style).

- Outcomes: Depending on the players’ objectives and approaches to the game, there may be one or more than one winner.

- Resources: Players are given limited amounts of deliberation time, nukes, shields, and health.

- Rules

- Players may only communicate during deliberation phases.

- Players may only take 1 action (nuke, shield, do nothing) per action. phase; they cannot peek at others’ actions.

- Players are eliminated when their health counter reaches 0.

- Players lose 1 health when hit, unless they use a shield.

- Players win 1 or 2 points for every objective they complete.

- Shields can only block 1 nuke.

- Shields are exhausted even if no one attacks.

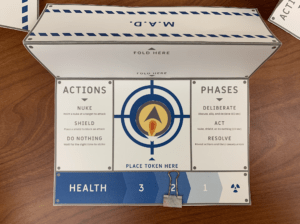

- Procedures

- Deliberation (60 sec): During this time, players discuss their move, create alliances, and / or deceive others to take an action in their favor.

- Action (10 sec): Following the deliberation period, each player takes an action. Players may nuke a player, shield, or do nothing.

- Resolution: Actions are resolved after the action phase.

- The game cycle (deliberate → act → resolve) repeats until the game ends.

- The game ends when all but one player are eliminated, or when all nukes are exhausted. The player (or players) with the most points wins.

- Boundaries: MAD is ideally played on a tabletop, with the players facing each other in a circle. It can also be played while sitting on the ground. With the player boards in front of them, players can construct a conference-like atmosphere similar to that of negotiating ambassadors representing different countries.

Types of Fun

We intended to create a social game with the aesthetic of fellowship at its core. That said, the aesthetics of challenge and fantasy also came to play important roles in the game as it was developed.

- Fellowship: To achieve their ends, players must deliberate. The fun of fellowship comes from the freedom to discuss strategy, form and break alliances, bluff, and deceive others to advance their interests and win the game.

- Challenge: Conflicting objectives, lack of transparency, and limited time to deliberate make winning the game a challenge. Players must navigate a path to survival and success by figuring out when to attack, defend, and bluff; who to trust; how to form alliances, find common ground, and discover the motives of other players.

- Fantasy: Players adopt the necessary personas to advance their interests, which are informed by their unique objectives as well as the game’s premise of a nuclear standoff.

Testing & Iteration History

We conducted playtests with 4 different groups of people, including ourselves. All groups consisted of Stanford students in CS 247G, and ranged from 3 to 4 people. After each playtest, we documented the feedback of the playtesters, then convened as a team to discuss major findings, and how we might improve the game accordingly.

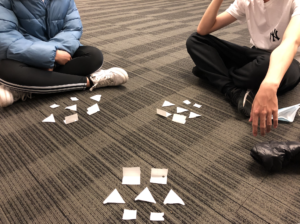

Initial Gameplay

Originally, we envisioned a game where each player had 3 reusable tokens (2 nukes and 1 shield). After deliberation (60 sec), players would close their eyes and choose 2 tokens to place on their left and right, respectively (10 sec). The tokens indicated the actions each player took against their 2 neighbors (attack or shield). Players who were attacked without a shield were eliminated, and the process continued until either only 1 player survived or all players were eliminated.

Iteration 1

After playtesting this game ourselves, we identified the following issues:

- Players only had 1 life, and were often bored when eliminated early.

- Players had no incentive to conserve resources, as tokens were reusable.

- Players could only take direct actions against their immediate neighbors, and so were limited in their ability to discuss overarching strategies.

The following changes were made in response:

- Replace the reusable tokens with exhaustible (one-use) nuke and shield tokens.

- Nukes can be directed at any player (point the tip at who you are attacking).

- Nukes double as HP counters. Players lose 1 nuke each time they are hit. Players hit without shields or nukes remaining are eliminated.

- Shields can only block 1 nuke (this prevents shields from being overpowered).

- Shields are exhausted even if no one attacks (this prevents shields from being overpowered).

- Players can choose to do nothing as an action (this introduces more complexity to the game, as players can pursue baiting strategies where they waste their opponents’ resources while preserving their own).

Iteration 2

We wanted to test how balanced the gameplay would be based on the resources given each player (nukes / health points and shields). We also wanted to see if the rules of the game were straightforward, enjoyable, and compelling enough to foster the engaged social dynamics we intended. This round of playtesting was done with 4 CS 247G students. Here are the major observations:

- The gameplay was smooth and engaging. Players engaged in heated discussion about what to do. These are very promising results.

- Some players deceived and backstabbed to win out. These players were often, but not always, punished by the collective (eliminated first). This is also promising because we wanted a game where players can pursue both cooperative and aggressive strategies, and had to be crafty to win.

Here are the major feedback points:

- Players felt shields were underpowered and often wasted (used without blocking any nukes).

- Players felt nukes were too weak. Since nukes are also health points, you need to spend a nuke to cancel a nuke of your opponent. But since both the aggressor and the victim lost a nuke, the aggressor is not really rewarded much.

- Players wanted a way to have their resources (especially nukes) replenished during the game.

The following change was made in response:

- Players who attacked unshielded players were allowed to keep their nukes.

We felt that this change was a clever fix that would address all 3 feedback points. With the rule change, attacking an unshielded opponent results in a net loss of 1 nuke / health for your opponent (as opposed to 0 before). Because the rule only applied to unshielded players, shields become more useful. Finally, we felt that being able to keep nukes when attacking unshielded opponents would eliminate the need for nukes to be replenished.

Potential changes we considered but did not implement:

- Nukes cancel when two players attack each other simultaneously (we decided this was unrealistic and went against the premise of the game).

- Decoupling health points from nukes and having a separate health counter (we held off on this idea because we wanted to keep the game simpler).

Iteration 3

Since we felt the atmosphere of the game was already quite desirable, we mainly wanted to see whether the new rule (players who attacked unshielded players keep their nukes) was feasible. This round of playtesting was done with 3 CS 247G students. Here were our observations:

- Players were confused about when they kept or discarded nukes, and how many nukes they lost. They often looked to the moderator for instructions instead of trying to resolve actions themselves.

- Players found it hard to orient their nukes at who they wanted to attack with their eyes closed.

We concluded that the latest rule (players who attacked unshielded players keep their nukes) was too convoluted. Our goal then became to keep the game playable, but also to resolve the issue of underpowered nukes.

The following changes were made in response:

- Decouple nukes from health points. Make a health counter to keep track of player health.

- Make a player board for each player. Player boards will feature a removable covering (so players can decide their actions in secret without closing their eyes, then reveal them afterwards), a reference to rules, and a place to put your selected token.

Iteration 4

We mainly wanted to see whether the new features (health points, player boards) resulted in smoother gameplay. This round of playtesting was done with 4 CS 247G students. Here were our observations:

- When told that there could be more than 1 winner, players cooperated in trying to maximize the amount of winners by exhausting all their nukes non-lethally and forcing the game to end.

In addition, here are the major feedback points:

- Players felt there was little incentive to eliminate other players.

- Players suggested a shared stockpile to replenish nukes and shields, and perhaps gain other resources.

- Players suggested unique, hidden objectives to increase the complexity of the game and incentivize taking actions against other players.

We had not anticipated that a group of players would cooperate to maximize the amount of winners, without the presence of backstabbers. We also thought it would be fun and realistic if players had secret, conflicting agendas. Thus, we decided to make the following adjustments:

- Create objective cards. Each player receives an objective card at the beginning of the game (“eliminate or protect a particular player”, “be the only survivor”, or “be the first to die”); accomplishing the objective wins you 1 or 2 points.

- Instead of being the win condition, surviving the game wins you 1 point.

- At the end of the game, the objectives are revealed, and the players with the most points win.

Potential changes we considered but did not implement:

- Creating a stockpile of resources (we felt that the aforementioned changes were sufficient to increase the complexity of the game, and did not want to make the game overly complicated).

Game Art, Information Design & Marketing Materials

Initial Designs

To playtest the game, we initially relied on paper tokens made from lined paper. Designs were crude but easily distinguishable. The nukes were triangles (which can be pointed at the target player), the shields were L-shaped flaps, and the health tokens were squares.

Finalized Designs

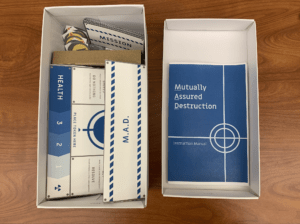

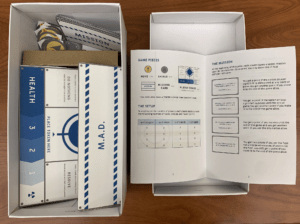

Because our game draws its narrative from nuclear warfare, we wanted an overarching design scheme that fit this theme. Our design features cold, metallic blues and grays. Crosshairs, danger tape, rivet heads, and the radioactive symbol are common motifs featured on all props and marketing materials (box, tokens, player boards, objective cards, instruction manual). All such designs draw its inspiration from the cold, industrial look and feel of military installations and nuclear weapons (see “Final Prototype” section for visuals).

Final Prototype

Playtest video: https://youtu.be/JdPrzqPJNl8

Instruction manual: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1bH4XKyDr1Uxe8DxFEO5AEyof24D55I7-/view?usp=sharing

Print-n-play: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1a0UPjtVj8DqOhUaQQhZqESJysGDvrjXC/view?usp=sharing

Visuals