Game: One Night Ultimate Werewolf (and its parent game, Ultimate Werewolf) were designed by Ted Alspach and released by Bézier Games, Inc. It is played as a physical board game, but a mobile device is used to give the initial “waking up” prompts and to keep time.

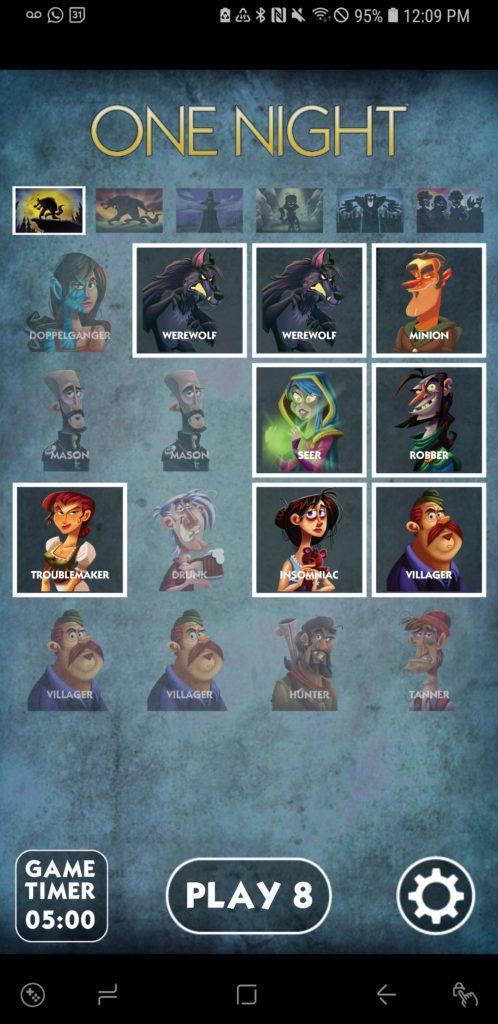

Formal Elements: One Night Werewolf could be played by 3-10 players (I was surprised that its parent game Ultimate Werewolf could be played by up to 75 players!). Each player is assigned a role (Werewolf, Seer, Villager, Robber, etc.), and, based on those roles, they “wake up” at a specified time during the first few minutes of the game when everyone has their eyes closed to perform those roles. This could include actions such as swapping two other players’ cards or looking at another player’s card. Once the eyes closed period is over, the entire group then has a set amount of time–10 minutes when I played it–to discuss what their roles were and to find the werewolves. There are no more formal actions to take except to vote at the end of the 10 minutes on who the werewolves were. If the non-werewolves team is correct, they win, otherwise, the werewolves team wins. And, notably, this game is played with only one “night,” or one round. Lastly, the player relationships are interesting because there are lots of bluffing and double-bluffing that could happen, and it goes from a straightforward social deduction game to one where players are sometimes rewarded for being taciturn or intentionally acting suspicious, especially if there is a Tanner role in the group.

What kind of fun: This is the challenge, expression, and fellowship types of fun. It is a challenge because both bluffing and figuring out who was lying were hard, and when enough people were playing–I played with 8–the chaos was fun, too. It is expression because of the roles involved, and how people started to take on their roles through their acting, bluffing, and team-ups. Some people even started to weave a story around their night’s activities, and that spiced up that round of the game even more. Finally, it’s a fellowship type of fun because there are clear team objectives (werewolf vs non-werewolf teams), and even though you may not know who is on your team, you have to trust at least a portion of the group to get to a decision when voting. Plus, obviously, the werewolves (and minions) are working together.

Improvements: The villager is a relatively boring role to take on. It is useful because it is easy for someone to claim to be a villager at the start of the game and so gets the ball rolling, especially since players with special roles often wanted to wait to state or lie about what their roles were. However, once that was over, the villager often had no opportunity to further bluff or act their role. They could still try to help their team, but their active role was diminished. I would try a version of the game with no villagers. In the end, this may throw too much chaos into the game, but it would possibly be a good improvement.

Comparisons: This game is similar to Mafia and somewhat similar to Among Us. I enjoy it more, because the change of being an unexciting role such as the villager is low, whereas in Mafia, it is high (with only a few special roles), and with Among Us, the time to complete mindless tasks is boring. Also, both Mafia and Among Us have “dead” players who are no longer as engaged in the game, so the one-round format of One Night was great. Lastly, not needing one person to sit out as in Mafia promoted engagement from every player.

Vulnerability: You don’t need to get vulnerable at all, since the objective isn’t to get to know your groupmates better.

Visuals: The packaging design for this game works very well. The detailed but exaggerated artwork on the characters sets the tone for the “expression” part of the game. Also, the darker, cool color scheme (but still colorful) makes the messaging that this is a bluffing game where the teams are playing against each other very clear.