For this week’s critical play, I played Fake Artists in New York, a hidden role drawing game designed by Jun Sasaki and published on Oink Games, played analog or a mix of analog and digital. The game is marketed for 5-10 players, published in Japan, and marketed for players of all ages. Players are assigned to be either a real artist or a fake artist. Real artists are given the category of object to draw and the name of the specific object to draw, fake artists are given only the category of object to draw. In the analog version of the game, there’s only one fake artist. In the digital-analog version of the game, there’s either one fake artist, all fake artists, or no fake artists. Players each take turns contributing to a single drawing, making one continuous stroke at a time, and each player gets two total turns making continuous strokes and contributing to the single masterpiece drawing. After each player has gone twice, players deliberate and discuss among themselves for two minutes who they think the fake artist is, and they guess the fake artist among themselves. If they guess the fake artist among themselves, the fake artist gets one chance to redeem themself by guessing the named item in the drawing. If they don’t guess the fake artist among themselves, the fake artist wins the round.

I played the game looking for a few elements: where the source of in-game “fun” was, how the game chose prompt topics for users to draw, how the game timed each round, how the game integrated all users as active participants in the game, and how the game tied in competitiveness and tracked points.

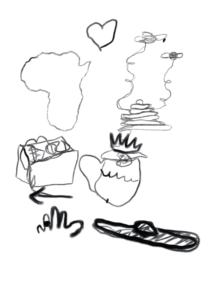

The source of in-game “fun” laid in the challenge of creating drawings that would not give away the drawing to the fake artist, but at the same time conveyed that the artist drawing was not the fake artist, and knew the prompt. The “fun” was not single-sided and limited to the currently drawing artist — the fake artist was also equally challenged by simultaneously trying to guess the prompt from clues from the other artists, while also trying to add elements to the drawing and showed that they knew what the other artists were doing. The “fun” was the intellectual activity of guessing, arguing, and creatively drawing — players exercised creative and logical skills while playing.

Our own game challenges the “government” to be creative in developing censors, and the “artists” to be creative in developing drawings that are difficult to censor, yet the “public” is left with a huge swath of time in which they have no tasks at hand. We brought down the time limit from 5 minutes to 1 minute, which made drawing prompts that included celebrities and human faces difficult to complete in 1 minute, but left the “public” less time to wait around and get bored.

Fake Artists in New York laid out 10 minutes to complete each drawing and prompts ranged from “Donald Trump” to “Stomach” and “Childish Gambino.” 10 minutes felt like the sufficient time needed to draw human faces and really detail out our drawings, two rounds felt like sufficient time for the fake artist to guess the drawing without really knowing the drawing, and the more we played (a total of five rounds), the more abstract our drawings became, often including elements related to the object at hand without ever directly drawing the object.

In our first drawing of the stomach, players drew everything related to the digestive system.

In another round for the prompt “Beyonce,” players drew items like a beehive, a ring on a finger, and a box to put everything in as references to “Beyonce.”

Finally, in terms of how the game tied in competitiveness and tracked points, the game did not need to explicitly track points to have a “winner,” but rather the fun lay in deception for the fake artist, and the fun in the creative exercise for the artists of deceiving the fake artist. No one quite seemed to care about winning — so long as the prompt was interesting and the players were invested then the game was still fun. There were moments when we were looking for a better prompt than the one we were given, and there was no way to do that without someone reading the prompts, meaning that the person selecting the prompts would not be a fake artists. I wished there had been a way for players to include a range of prompts, or select from a range of prompt options, or choose a category pre-sorted for them, such that they had control over the prompts without explicitly reading prompt options.

Our own game has focused on the challenge aspect more than the fellowship aspect of gaming, resulting in a heavy focus on how to delegate point counts, which have made the game more complicated than need-be. The important feature is that the game is “fun,” and moving forward, experimenting with different prompts and time limits, as well as the creative aspects of the game more than the challenge aspects of the game, is particularly important.