For this assignment, I played Secret Hitler (board game developed by Goat, Wolf, & Cabbage) with ten members of my dorm. It’s a social deduction game that targets small to medium sized groups (5-10) and on first impression, requires at least a middle school level education or maturity level (although it doesn’t really require knowledge of historical elements).

As for the starting action, each team is divided into two teams: liberals and fascists. All liberal cards are the same but one of the fascists is designated as “Hitler”. The fascists have knowledge of the other fascists (including Hitler) but the liberals are given no information upon setup. Also, the number of fascists is dependent on the number of players in the game.

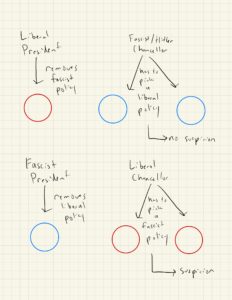

The game operates in a clockwise manner where at each round, there is a “President” who is able to elect a “Chancellor”. Players vote in favor or against the current Chancellor who, if elected, can enact either a “liberal” or “fascist” policy on the game board. In this case, the President will draw three cards (containing either liberal or fascist policies), remove one, and hand the other two to the Chancellor who then picks one of the cards to place it on the game board. If a Chancellor is not elected by majority vote, the round is over and the President moves to the person to the left. Thus, the liberal team wins by enacting enough liberal policies and the fascist team wins by enacting enough fascist policies (outwitting the liberals). Fascist policies can grant the President certain powers such as inspecting a player’s card or removing a player from the game and if Hitler is removed, the liberals win. On the other hand, if the fascists have three passed policies and Hitler becomes Chancellor, then the fascists win.

The game mechanics are similar to Werewolf in that Secret Hitler relies on both social deception and coordination to cause players to either infiltrate a group or to succeed at some goal in spite of malicious actors. There are distinct similarities between the games such as the shared theme of the “seer” in both games and the elimination of players (although they only occur once in Secret Hitler). However, one key distinction is that Secret Hitler utilizes a board to drive the game forward and allows for a more engaging way of facilitating the social experience in comparison to Werewolf. Personally, the most interesting aspect of the game was the dynamic of needing to draw policy cards since a fascist could either receive two liberal cards and force a liberal policy or the other way around with a liberal (if a supposed liberal had to place a fascist policy, they needed to defend themselves against their actions). I noticed that this occurred relatively frequently and allowed for frequent moments of ambiguity where seemingly benign players suddenly became suspicious to others. Overall, these moments introduced well-paced conflict within the game (between liberals and liberals, between fascists and liberals) and because of this, I thought that the game was fun to play.

Additionally, the way Hitler was played between the two games that I played was interesting to observe. In the first game, the player who was Hitler was loud and incriminating in the discussions whereas in the second game, Hitler laid low and tried not to cause any suspicion. I personally thought that the player who played Hitler in the second game did a more effective job since the first Hitler was easy to deduce but the second one did not cause any suspicions (although the other fascists were still loud regardless).

One moment of failure was in the overall setup of the second game when the fascists happened to be all lined up together. In fact, all of the fascists were President in the first few rounds and so the game swiftly ended with one long streak of liberal policies afterwards. However, I believe this was due to bad luck and do not think this bug affects the game substantially over many plays.

In general, these types of games are fun and effective if they allow the malicious team to win at a high rate but also not too easily. In Werewolf, eliminating the seer in the first few rounds made it substantially harder for the villagers but having an almost guaranteed seer in Secret Hitler allowed the “seer” role to actually play into effect. On the other hand, although the liberals did win both times in my game play, it was clear to see how the fascists could win because of the ambiguity of the cards and the possible chaos of the voting mechanism. One thing I might change (or would be curious to see changed) is the transparency of the voting process. In each round, every player’s vote for the Chancellor was public which allowed some players to somewhat deduce roles in later rounds. However, the game might offer an even livelier dynamic if the votes were kept secret and people instead needed to speculate further on who voted for what.