For this critical play, I played Hungry Hearts Diner on iOS. This game combines the mechanics of diner management games (ala Diner Dash) and idle games, with a rich narrative and strong cast of characters.

Mechanics: The player plays as a grandma running a Showa-style diner in rural Japan. They prepare food, serve them to guests as they come in, and collect their payment once they are done. Preparing food requires energy, which is repleted as real time passes (1 minute = 1 unit of energy).

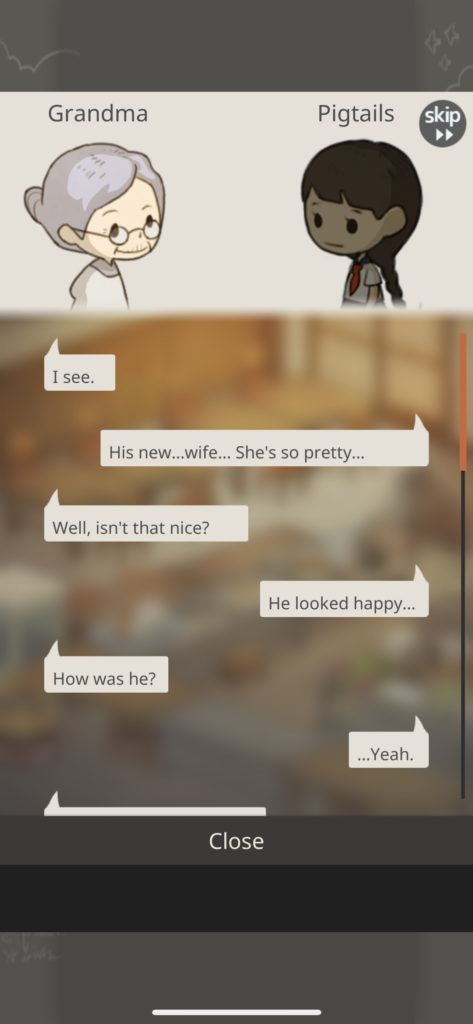

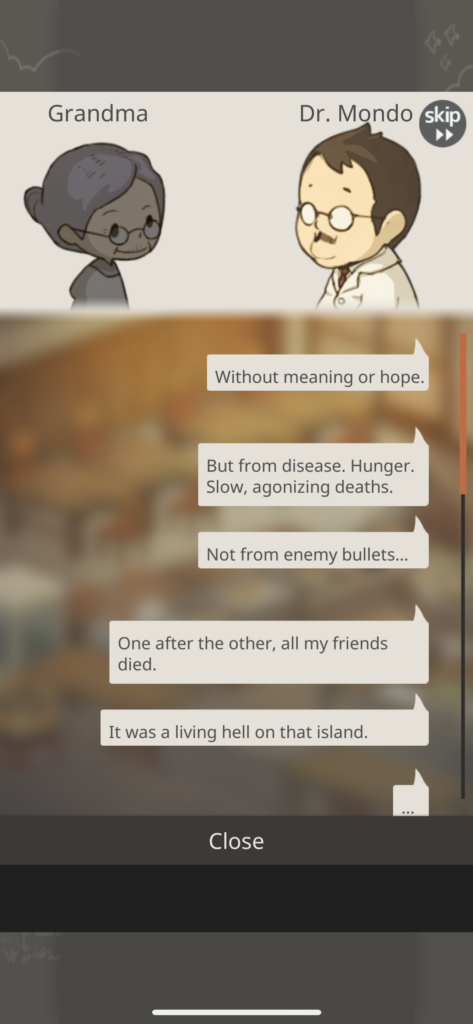

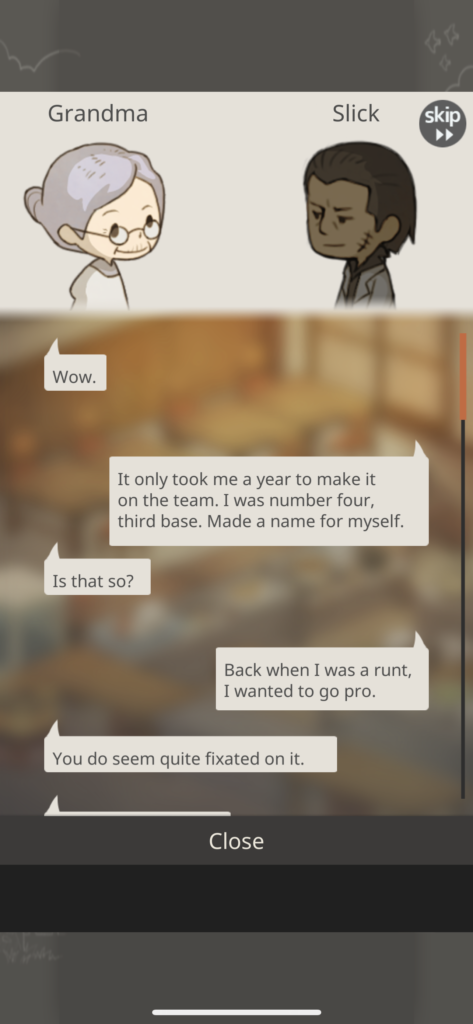

Story: The player advances through the main character’s own story, which is about the grandma taking over the diner after her husband fell ill. As she takes care of her husband, she is also encouraging him to reconcile with their daughter, who he has disowned after her marriage with somebody he disapproves of. At the same time, the player talks to and learns more about the frequent guests at the diner: a schoolgirl who is dealing with her parents’ divorce, the local doctor who is haunted by his service as a military doctor, a gangster who used to dream to be a pro baseball player, etc.

Some of the characters the player meets during the game.

Loops and arcs: In the simplest terms, the mechanics of preparing and serving food serve as the main interaction loop, and the advancing story (of both the main character and supporting characters) is the main arc. However, the game also utilizes arcs in the mechanics. As the player prepares dishes, the level of that dish increases, and certain r ecipes are only unlocked once another recipe reaches a level threshold. The player’s “diner level” advances as they prepare dishes, and they can unlock “upgrades” that makes their preparation time faster or allows more guests to be seated in the diner. These arcs within the mechanics create the feeling of achievement and progress.

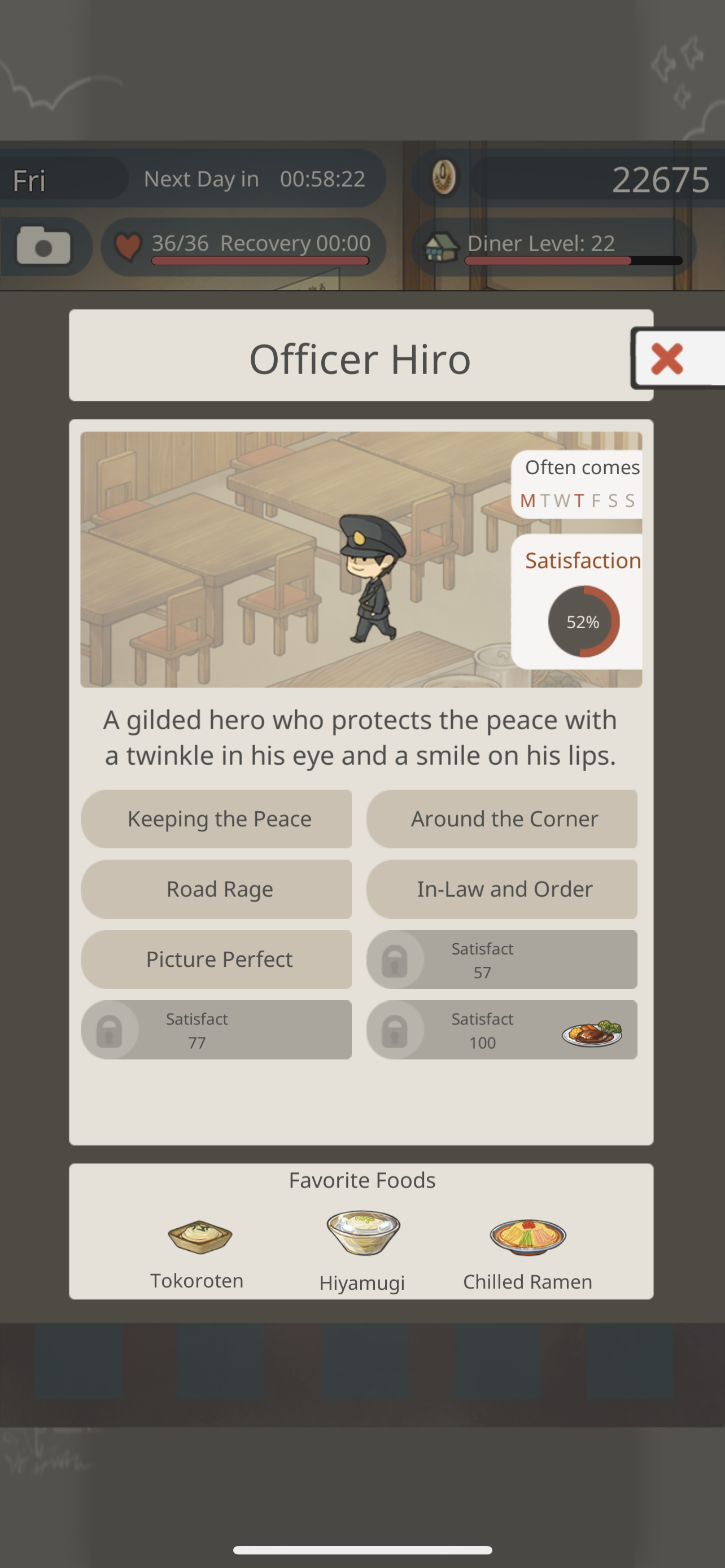

A type of arc within the mechanics — certain recipes require another recipe to reach a level threshold to be unlocked (for e.g. to make Chilled Ramen, the player needs to make Ramen enough time such that it is level 6).

The mechanics and the story are in general kept separate from each other, even though the story of each character is advanced based on how many times the player has served that character (through the mechanics of preparing and serving food). The most notable interaction between the mechanics and the story is that certain “chapters” in characters’ stories can only be reached after serving that character a particular dish. This creates a motivation within the narrative to advance through the arcs of the mechanics (levelling up dishes so that the required recipe can be unlocked).

Mechanics and story interacting: to unlock the last chapter in Officer Hiro’s story, the player needs to serve him a certain dish.

Both the mechanics and the story of this game are very simple compared to a game that is purely about diner management or story. In terms of mechanics, the player makes very few interesting choices, such as what dish to make, and very rarely, what upgrade to buy. This is in contrast to other diner management games, where players would need to make a lot of decisions, for e.g. where guests sit, what dishes to cook first, who to serve first (in Hungry Hearts Diner, guests can get upset but they would never leave). The player can never make a mistake with a dish (no burned food) and cannot throw food away, and guests only order from the food already prepared. The story advances without any player’s input in terms of what would happen in the narrative (in contrast to most other narrative games).

Choices re: mechanics are quite limited in Hungry Hearts Diner — guests will only order what the player has prepared, so there’s never a concern of having to throw away food and wasting money (a common dilemma in other diner management games).

I would characterize this game as having narrative as its main aesthetic goal, and perhaps also submission (I definitely spent a lot of time playing it). The mechanics serve as a way to slow down the payload of narrative content (so players would have more time to care about the characters?). The advantage to slowing down the narrative in this manner is that it still allows the player to engage meaningfully with the narrative world during “downtime” — as opposed to having to wait a certain length of time to “unlock” the next part of the narrative.