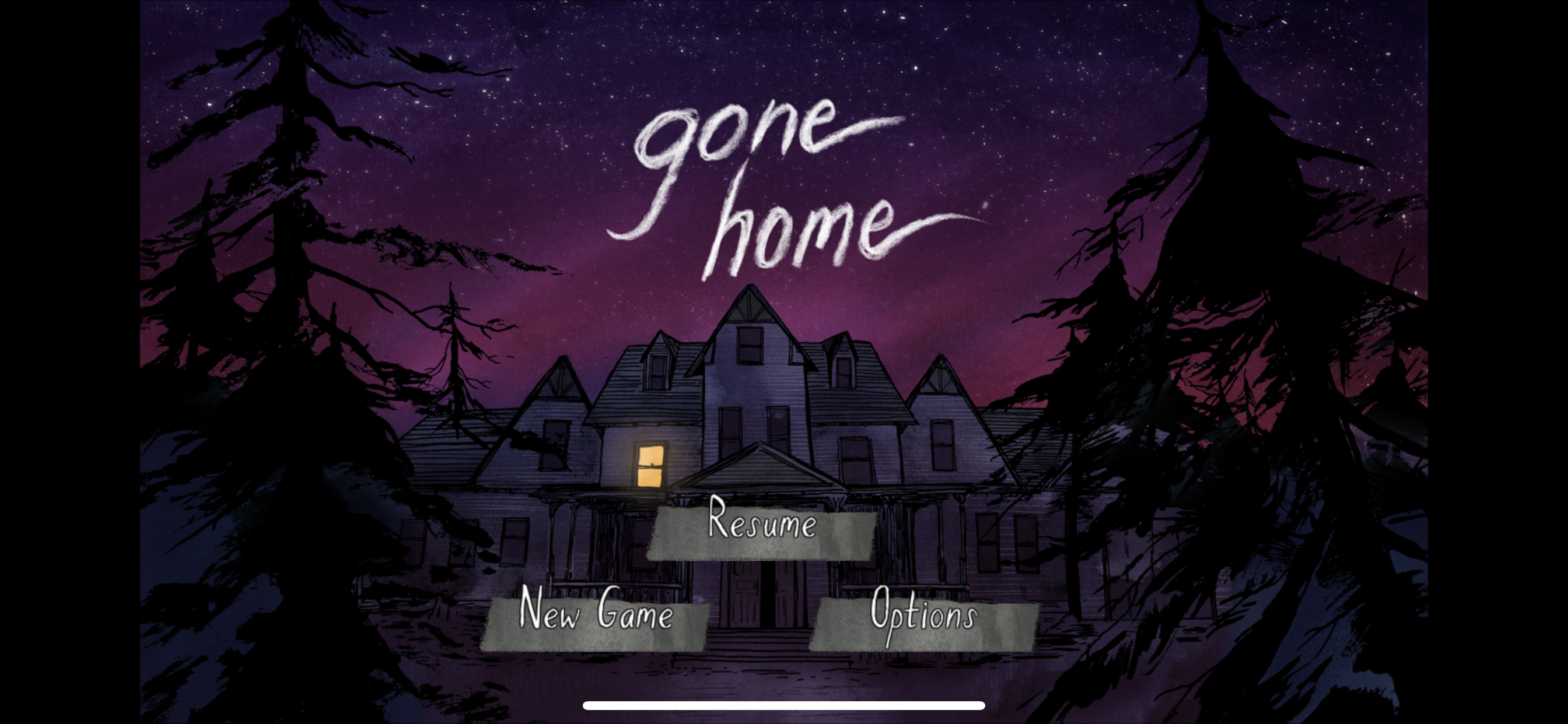

Gone Home is a first-person exploration walking simulator developed by The Fullbright Company, first published on 15 August 2013 for Windows, OS X, and Linux, ported over to the PlayStation and XBox in 2016 and the Switch and iOS in 2018. (I accessed this game through the iOS app, which may affect my commentary on the mechanics.) This game is targeted towards players who appreciate exploring and experiencing a created space, with no forced objectives besides the internal motivation of investigating the embedded mystery narrative and piecing together clues to find the “truth.”

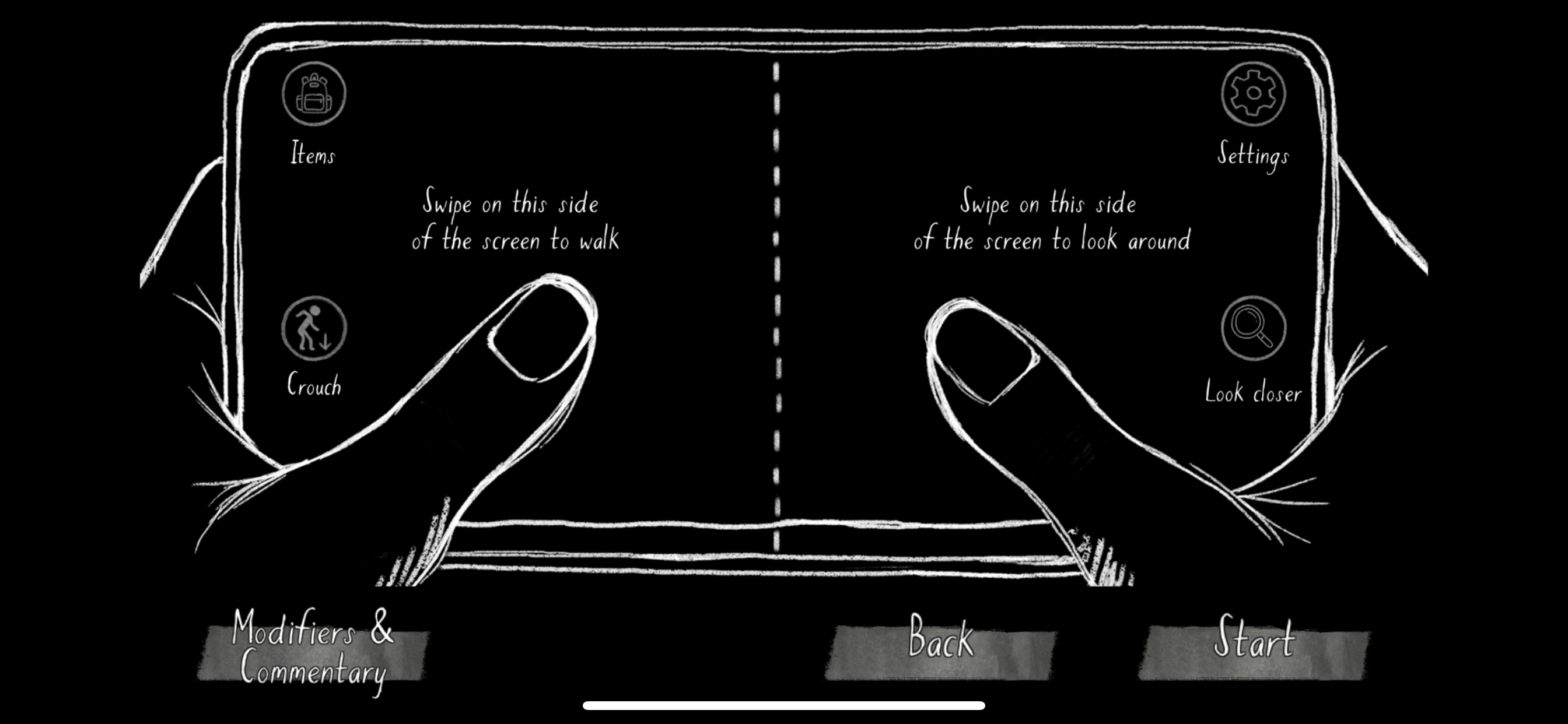

The beginning scene is of particular note for how it introduces the core mechanics and narrative throughline to the player, with the “puzzle” elements of finding a key to unlock a door. The player first arrives at the front porch of their family house, surrounded by their bags and various empty cabinets and tables with clutter. From reading their bag tag and passport, the player can discern that they are playing as Katie, a student returning from her Europe trip to an empty house and an absent family. In the beginning scene, the player learns how to tap on the left screen for movement, and to tap on the right screen for switching the camera perspective. In their initial explorations, the player will find the front door locked, with a hastily written note from their sister Sam warning them not to look for her. With this context, the player is incentivized to find a way to unlock the front door and investigate this mystery of their missing sister, which leads them to walk through the limited porch area, pick up tappable objects, and look closer and rifle through the containers, such as the cabinets, until they find the house key. As part of this process, they will find that tappable objects are marked by the appearance of floating white text like “open door” or “pick up cup.” This closed opening scene provided a gentle walkthrough and set the expectations for the game’s mechanics as emphasizing movement and investigation over other controls. Likewise, this subtask also enhances the story in that this particular subtask — finding a key — also cues the player to wonder why their family home is apparently deserted, and prompts the player’s investigation objective. Where is the player’s sister Sam, and why did she disappear?

Types of Fun Intended

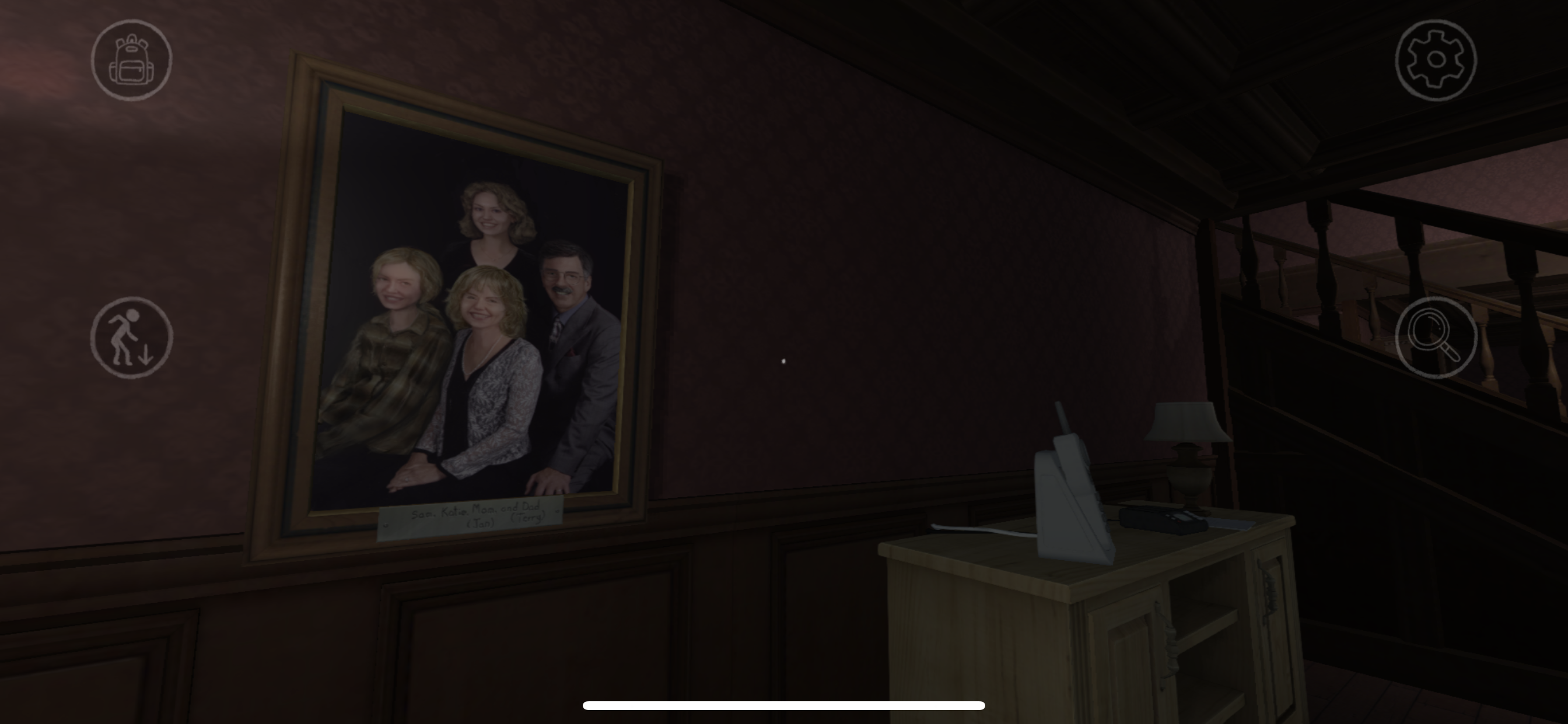

The core type of “fun” in this game is Discovery and Sensation, with how the gameplay emphasizes exploration and piecing together clues, even as it is tied to a specific sense of space and time, a family home in a rural part of Oregon, 1995, with the sounds of a frosty gale and low lighting. The walking simulator aspect lends itself well to the player’s sensory discovery, as upon entering the house there is only one automatic light in the center stairs, and the player must tap on the lamps to turn them on and help them see and examine clues better. Encouraging the players to interact with the space for light (which is normally an ubiquitous element in real life) to see further enhances the eeriness of the empty house and adds to the search, as the player may overlook clues and details if they do not find the light switch to help them spot details here and there. Since the player is alone save for a few haunted family portraits, the occasional creaking floorboards, voicemail, and wind further adds to the experience of solitude, especially as the player’s central motivation is to find why their sister Sam left.

Possible Areas of Improvement

Unlike Dear Esther, this game did not have a specific path through the house that would reveal a more chronologically-linked narrative, as the player is free to wander the rooms in any order, besides for locked doors that require a deeper rummaging through scattered debris to find the keys. While the player can stumble on contextual clues, such as a mother’s forestry badge or an old newspaper clipping of the former house owner, because there is no strict spatial traversal, the narrative timeline also suffers from a lack of clarity. Without revealing the ending revelations (including the queer love story), because there is no curated, emotional leitmotif besides the initial Sam letter at the start of the game, the player may lose motivation to continue midway when they also cannot move onto the locked rooms due to “Hunt the pixel” puzzles (of having to look and touch through all the objects in a large house, to find the relatively miniature keys). Though part of the appeal of the game is its realistic setting, with a discombobulated player searching through a cluttered house to figure out why their family is missing, the mundanity of only finding scraps of letters and piecemeal can drag the story with how the repeated mechanics offer little change besides new and different information.

Likewise, this is more a critique of the platform than the game (which was ported to mobile 5 years after it was first released on PC and Mac), but I find that similar to my experience playing Dear Esther on iOS, the mobile app experience for walking simulators first designed for the computer is that while some parts of the immersive experience translate (wandering and exploring a new space), the small screen-size and somewhat unintuitive controls seemingly prevent players from having the same experience as gameplay on a larger screen with joystick movement and mouse camera control. I would wonder at how walking sims can be better adapted for iOS in future critical plays!