About the game

I can confidently say that I have never played a game like Goragoa! It’s a deceivingly simple, yet complex video game puzzle developed by Jason Roberts and published by Annapurna Interactive. I played it on the Nintendo Switch. The game requires the player to manipulate tiles set on a 2 by 2 grid in order to find patterns, arrange elements, and unlock progress towards furthering the story. It is a highly visual game, as it requires players to use visual cues in order to solve the puzzles within the constraints of the game.

Formal Elements

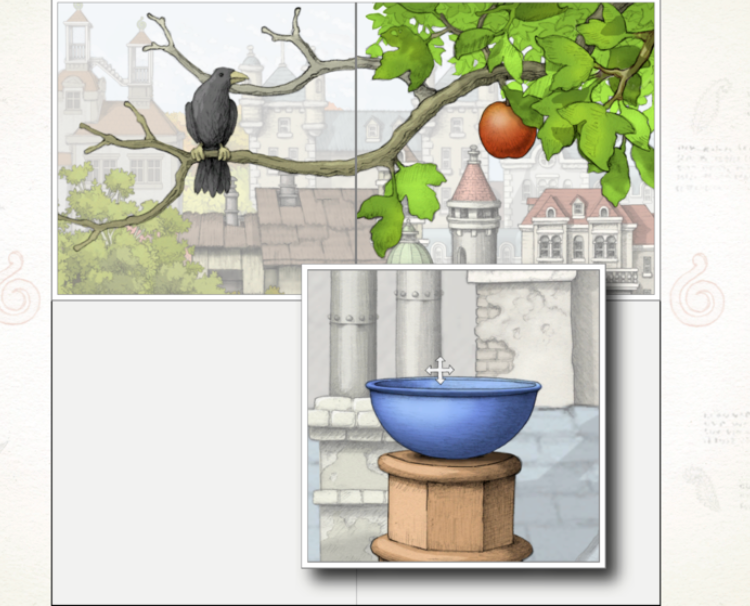

In my opinion, the most important formal element in this game is the boundary. The game revolves around “magic squares” rather than a “magic circle.” In other words, the boundary of the game is defined by the 2 by 2 tile grid and the tiles that can occupy each of the 4 spaces. Each tile itself has its boundaries as players can interact with elements to zoom in and out of the scene to reveal detail or context in the scene.

Players can interact with one scene at a time, and so sequencing becomes important as players aim to find the right level of granularity across tiles in the 2 by 2 grid to unlock the next stage of puzzle play. For example, two separate tiles may share some visual similarity implying that they might be parts of the same scene. It is up to the player to recognize the visual clues and then arrange them in the right pattern (e.g., next to each other or on top of each other on the grid) to form a holistic picture. When this happens correctly, the game advances to the next stage or scene of gameplay.

Tiles can also be superimposed on each other to unlock an interaction. This happens often with circular shapes, windows, and doors that allow the protagonist to move into different scenes. The sequencing matters here, too, as the door must be moved to the protagonists’ scene and not the other way around.

The grid is a deceivingly simple constraint and boundary, and yet it offers a lot of flexibility in terms of what can be allowed within the squares. Illusion plays a big role in the game and certainly communicates a sense of magic when the elements come together in just the right way to unlock the puzzle. The boundary of space is what holds the game together. Without it, the elements could not come together and the game as we know it would seize to exist.

Types of Fun

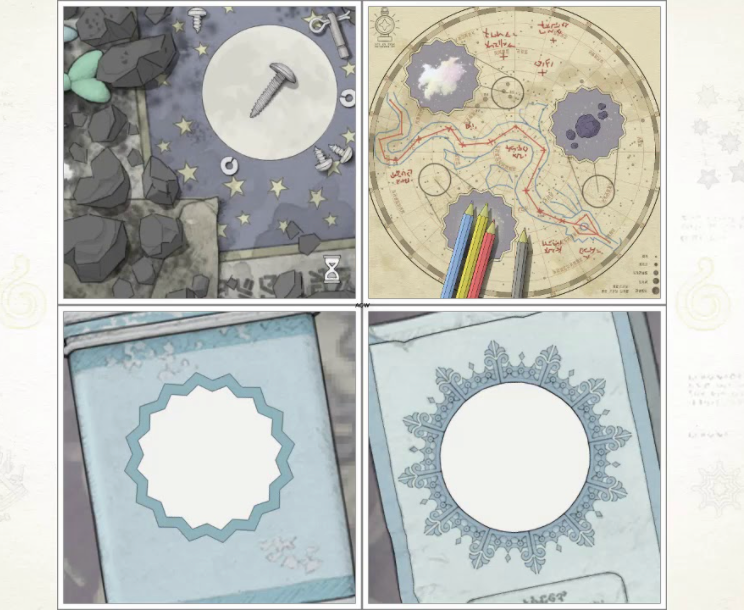

Challenge is the primary type of fun promised by Goragoa. Though there is a narrative, the player does not need to follow or understand it clearly in order to enjoy the game. For example, as a player, I was able to deduce that one of the themes is about the cosmos, given that there are visuals of stars, constellations, light, and meteors featured throughout the game. There are also a number of characters including a boy as the main protagonist. However, players know little about the people in the narrative and do not rely on understanding the story in order to advance forward other than understanding that the “light” needs to ultimately move to the right place. For example, a couple of puzzles rely on the light reaching a lantern in order to “turn on” or “light up” the scene.

It is interesting that the level of challenge and difficulty increases over time. At the beginning, the player is guided to interact with certain elements which makes each step clear, effectively guiding the player forward. As the game advances, certain puzzles become time bound and require a higher degree to “twitch” skill in order to complete. For example, there is a rolling ball that can fall into the tile below it, and then needs to quickly be moved to a top tile before the ball reaches the bottom of the tile, so that it can roll down to a third tile and break a glass enclosure around a captured butterfly. By releasing the butterfly, the story is able to continue into the next piece of the puzzle.

Moment of success

In the beginning, I noticed I was solving puzzles almost accidentally. Over time, solving the puzzles required more thought. For example, there was a physics inspired puzzle that required the player to manipulate the ends of a scale with cotton balls or heavier rocks in order to move the lantern to the other side of the plank. I was frustrated after mindlessly trying a lot of different configurations, but was still motivated to solve the puzzle which led me to reflect on logic. After pausing for reflection, I realized that some elements at my disposal were heavier and lighter than others, which helped me pick the right combination (light on one side and heavy on the other) in order to solve the puzzle. I felt a strong sense of relief and delight after solving that puzzle! It was a great moment of success in that it rewarded the player for exerting effort and not giving up. In other words, it delivers on its promise of fun through obstacles and challenges! Like Goldilocks, the challenge was not too easy, not too hard, but just right.

This experience reminded me of the quote shared by Laura E. Hall from Mike Selinker and Thomas Snyder on Puzzle Craft: “People like to solve puzzles because they like pain, and they like being released from pain, and they like most of all that they find within themselves the power to release themselves from their own pain.” I was in pain, and the release from it made the experience pleasurable.

To make the game better

I found myself as a player increasingly interested in the narrative. The story seems mysterious and a puzzle itself, which does lend itself well to intrigue. However, I didn’t feel incentivized to figure out the mystery of the story, as I was focused on figuring out the mysteries around each puzzle. Perhaps if there was more scaffolding or onboarding around the story, players can more fully immerse themselves in the universe with insight that would help them understand the scenes, landscapes, and intentions behind the puzzles. As Bob Bates shares in Designing Puzzles, puzzles can “divert the player’s attention from the story, destroying the magical experience the author is trying to create.” While my experience of the game was magical thanks to the creative mechanics of the grid and tiles, a clearer story would help amplify the player’s experience and connection to the game overall.