Introduction and Audience

For this assignment, I played What Remains of Edith Finch, a game developed by Giant Sparrow, on the PC. In my mind, it’s a little difficult to pin down exactly who the intended audience for the game might be. The game (at least up to the point I played) doesn’t feature any moments of intense action, or even any failure states I can discern. This might indicate that the intended audience is one more concerned with slow moments of contemplation and emotional storytelling. At the same time, however, What Remains of Edith Finch includes significantly more “action” and a wider variety of mechanics than some other walking simulators, like Dear Esther. It seems reasonable, then, that the developers were trying to expand the audience of typical players of walking simulators to include people who might be put off by a game consisting solely of moving and receiving narration.

Formal Elements

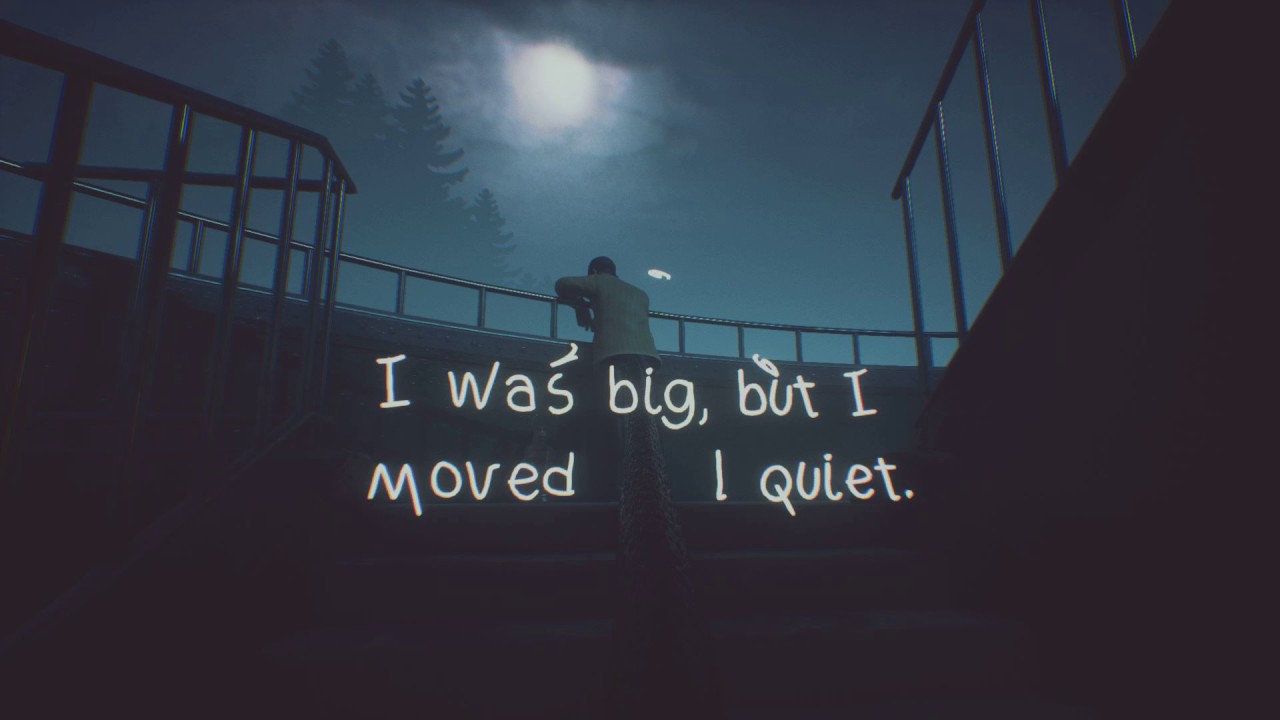

Of the formal elements, I think the ones most important to What Remains of Edith Finch are objectives and procedures. As mentioned above, outcomes don’t seem to matter as much, given the lack of any kind of dedicated fail state. Instead, players are invited to uncover the mystery of the Finch family, playing as a young woman returning to her family home after a mysterious incident forced her and others to leave in a hurry. There are no “objective markers” overlayed onto the screen, but as soon as players see the towering, strangely alien house in the distance, they are likely to feel compelled to find a way over and inside. Once inside, numerous potential rooms are presented to the player, but only one is accessible at a time. This helps present the impression of a grand mystery of story to uncover without overloading the players with one thousand objectives at a time.

I also think What Remains of Edith Finch does an excellent job of using a very sparse set of procedures / mechanics to tell its story. In general, your only options in the game are to move around, pan the camera, zoom in slightly, “interact” with certain objects when a contextual prompt appears, and, in certain limited cases, manipulate objects directly. This very restrictive set of actions helps prevent the player from being overwhelmed with options, even if they are relatively new to games. While the game doesn’t feature any kind of non-diegetic tutorial, the opening scene (in which you must use the camera to look down at a letter, use the interaction button the start opening it, and manipulate the letter to unfold it) serves to on-board players to the general control scheme. This is especially helpful when What Remains of Edith Finch starts changing who you control. In one segment, you play as, in sequence, a cat, an owl, a shark, and a terrifyingly tentacular monster. In each and every case, however, you keep the exact same control scheme, with the “interact” button simply serving a different, contextual purpose.

In this way, What Remains of Edith Finch uses construes “walking” in the broadest possible sense and uses it to tell its story. The medium of movement might change, but through it all there is a consistent emphasis on navigating through spaces and encountering objects which relate to the story. I think What Remains of Edith Finch is quite successful in telling its story and using diegetic means to introduce its relatively simple set of mechanics. If there was one thing I would change, it would be the option to start the game with a bit of tutorial in order to help people who, for instance, have never played a first-person game before.