Theme and Game Description

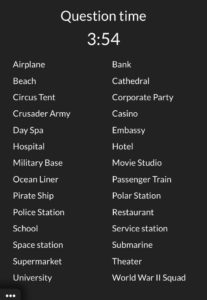

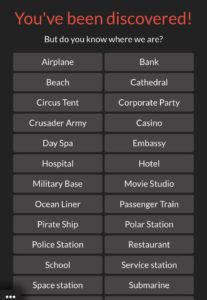

Spyfall is characterized as a communication, deceit, and deduction game suitable for 3+ players. The narrative for the story centers around “uncovering a spy through meeting”. Each player would be provided with a piece of information about the location they meet except the spy, and they would have a three-minute discussion trying to figure out who the spy is. If the spy figures out the meeting location in the discussion, the spy wins. If the players figure out who the spy is, then the rest of the players win.

Mechanics, Dynamics, Aesthetics, fun

The most key aesthetics of the game is fellowship, challenge. Challenge is created by the time pressure in the discussion section, in which the non-spies need to detect who the spy is as well as preventing the spy from knowing their meeting location. Challenge is as well created through opponent play, since the goal of the spy is directly antagonistic to the goal of the non-spies. However, through encouraging sharing a moderate amount of information between the players, the game as well achieves the goal of fellowship. It is almost impossible to detect who the spy is if everyone refuses to share information about their location with each other, and the spy would not be able to guess the location and not to be considered a spy if they do not actively participate in the discussion. This delicate interplay between “what to disclose/what to not disclose” allows the coexistence of fellowship and challenge.

The game involves slight fantasy and expression elements. Since it is named as “Spyfall”, it does encourage the players to imagine themselves as spies and non-spies, and the information as “meeting location” mimics some of the most typical spy narratives as well. However, personally, I think the fantasy goal is not conveyed very well in the game, and I would further explain the reasons in the insight section. Expression goal is achieved through the possible storytelling element that might be involved in the discussion section. There’s much freedom to gameplay, and one of the strategies that I personally would adopt in the discussion section is to make up background stories for my character to hint the meeting location in a subtle way.

As seen above, the fun that the game promised to the player is fellowship, challenge and fantasy. Depending on the specific ways that players choose to play this game, the game might as well provide a fun expression if the player chooses to customize their character during the discussion section through storytelling.

Insights

Graphic Designs

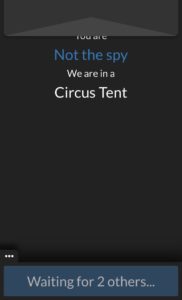

Sadly, I would say the fun is not reinforced through graphic design very well. One graphic design decision that I would commend is the part is that the game chooses to have the identity revealed through sliding up an envelope-like box, which somehow mimics the dramatic moment often depicted in popular culture in which secret agents discover their mission and identity through opening an envelope, giving players a sense of uncovering and revealing. Another graphic design point that I think we could learn from is how it uses font size and font color to emphasize important information.

However, I do think the graphic design of the game does not directly contribute to the fun. The interface is pretty simplistic, with the main color palette as blue, white and various shades of gray. The calm, mechanical feeling conveyed through the color and the lack of graphic design makes the player very hard to engage with the spy/not the spy role, thus not emotionally invested to defeat/outwit their opponents. The meeting locations, without any visual aid, is hard for the players to visualize, thus harder for the players to describe or interact with each other concerning the meeting location.

Other Insights

I choose to play this game because deceit, communication and deduction are also the concepts we want for our own game. One of the greatest insights I have from playing the game is about how to make all the roles in the game have similar amounts of interactivity: in this game, the spy and the none spies; in our game, the liar and the truth-tellers. One thing I like about this game is that it has the same amount of goals for you no matter which role you choose to play: if you are a spy, you would be having a goal to discover the meeting location, as well as a goal to hide your identity. If you are not the spy, you would be having a goal to discover the spy, as well as a goal to hide the meeting location. The goals of both parties are both discover and hide, and they are directly antagonizing each other. The good thing about this is that no matter which role the player gets, the player would be basically doing the same kind of thing in the game. Thus, there wouldn’t be situations where players find a certain role entertaining and more interactive, but another role lame and making them not want to play this round. (An example of this situation is werewolf: from my previous playing experience, I find out most people want to redraw the identity or feel really unhappy when they get the “villager” card, since villagers have significantly less interactivity compared to other roles.)

Another good insight I get from Spyfall is its utilization of timing. A good timing would create a sense of urgency and add excitement to the gameplay. We would consider adding a time limit to our discussion session as well. But I would hope to have more flexibility in timing in our game compared to this game. In Spyfall, there’s a strict timing for the discussion session, and you cannot proceed to the next step even if you finish the discussion in less than 4 minutes.