Depression Quest (2013) is a text-based interactive fiction game by Zoe Quinn, available for free on platforms like Itch.io and Steam. The game is designed for players interested in socially conscious storytelling and mental health awareness, especially those willing to engage with interactive narratives that challenge typical gaming conventions…

Playing Depression Quest as a feminist means engaging critically with how the game frames mental health, care, and societal expectations. Shira Chess’s Play Like a Feminist challenges us to see play as a form of resistance, an opportunity to question whose stories are told, who gets to play, and how systems of oppression shape lived experiences. In this light, Depression Quest is a powerful, yet limited, experiment in feminist game design. Its core mechanic of disabling certain choices to simulate the emotional paralysis of depression rejects traditional gaming narratives that glorify power and control. By forcing players to sit with discomfort, the game aligns with feminist theories of care that value vulnerability, emotional labor, and the slow, often invisible work of tending to oneself and others.

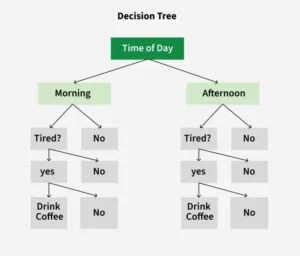

MDA framework

Using the MDA framework, Depression Quest relies on minimal mechanics, such as choice constraints, which create a dynamic of restricted agency. This design leads to an aesthetic of empathy, frustration, and reflection. The grayed-out choices visually reinforce the emotional numbness and powerlessness that often accompany depression. Unlike games that reward mastery or offer constant opportunities for success, Depression Quest invites players into an experience of subtle ‘stuckness’.

It asks players to feel, not fix. This rejection of the typical “power fantasy” represents what Chess would call a feminist reimagining of play.

Limitations

However, Depression Quest has important limitations when viewed through an intersectional feminist lens. The game presents depression as a largely universal experience but centers on a white, cisgender, middle-class protagonist (at least that was my impression). It rarely explores how race, gender identity, sexuality, or class shape mental health struggles in different ways. This flattening of experience risks erasing the reality that mental illness often intersects with other forms of oppression. Crenshaw’s theory of intersectionality reminds us that no form of oppression exists in isolation. A more intersectional Depression Quest might have included characters who navigate the layered challenges of racism, transphobia, ableism, or financial instability. Scenes where a character faces discrimination at work, an inaccessible healthcare system, or a family that stigmatizes mental health differently across cultures could have made the narrative resonate with a wider audience.

It is also important to contextualize Depression Quest as a product of its time. Created before the rise of large language models, the game uses a static, branching narrative structure, with every path written ‘by hand’. While its scope could have been broader, the technical and creative constraints of the medium limited what was possible. Recognizing these limitations does not absolve the game of critique, but it does remind us that feminist design is an ongoing process. Pushing for greater inclusivity is part of that work.

Ethics and the Limits of Representation

Depression Quest raises important ethical questions about the limits of representation in games. Can a single game truly capture the complexity of mental health across diverse identities and lived experiences? By focusing on a narrow perspective, Depression Quest risks reinforcing the idea that depression is a universal experience rather than a multifaceted one shaped by systems of power. This can unintentionally marginalize players who do not see their realities reflected in the game’s narrative.

At the same time, Depression Quest demonstrates how games can ethically approach sensitive topics like mental health by rejecting typical narratives that treat mental illness as something to “fix” or overcome through personal willpower. The game instead centers care, vulnerability, and emotional labor, aligning with Chess’s concept of feminist play. It invites players to witness and feel, not to control or conquer. This is an ethical approach to storytelling in games that prioritizes empathy over mastery.

For me, Depression Quest was a powerful reminder that games can cultivate empathy but also that they carry the responsibility to acknowledge the structural factors that shape personal struggles. Without attention to intersectionality, even well-intentioned games risk oversimplifying the issues they aim to illuminate. A more ethically robust Depression Quest would move beyond individual experiences and offer a sharper critique of the systems that exacerbate mental health challenges, such as capitalism, patriarchy, etc.

It would also strive to include a broader range of voices and perspectives, offering players a more inclusive and representative experience.

Depression Quest stands out in the interactive fiction genre for its bold design choice to remove traditional narrative agency. While games like Life is Strange and Firewatch allow players to make choices that shape outcomes, Depression Quest asks players to sit with the feeling of powerlessness. This decision is both its strength and its ethical risk – it creates empathy but may alienate players whose experiences are not reflected in the narrative.

Ultimately, Depression Quest is a meaningful intervention in gaming culture. By rejecting power fantasies and centering care and vulnerability, it opens the door to feminist play. At the same time, it reveals the limits of early narrative design and the need for more intersectional, systemic critiques in games that tackle complex social issues. It is a great starting point, but not a final answer.

I believe feminist play is not just about the stories we tell, it’s also about whose stories and how we tell them…

Very powerful narrative experience 🙂