In this critical play, the chosen game is A Dark Room. This single-player, text-based game was originally developed by Doublespeak Games and relies solely on textual descriptions and button-based actions. It appears to be aimed at a more mature audience, as very young players may not be as engaged by a gameplay dynamic that consists entirely of reading and clicking. Thus, the target demographic seems to be young adults to adults. The version analyzed in this review is the original web-based release, although the game was later adapted for mobile devices and the Nintendo Switch (see featured image as a reference).

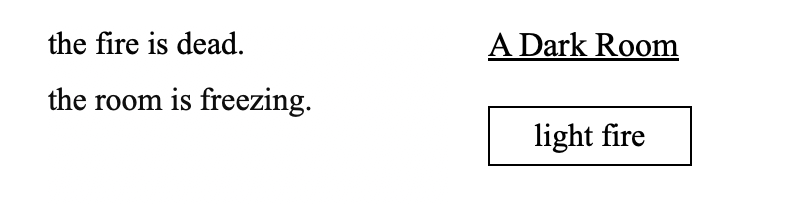

A Dark Room is extremely minimalist, and I must confess that it has the simplest opening I’ve ever seen in a game. It begins with a single button: “light fire.” Upon clicking it, a sequence of brief sentences appears — “the room is freezing,” “the fire is burning,” “the fire is dead.” Once you realize that you have only four pieces of wood, a new action becomes available: “gather wood.” From there, the gameplay gradually expands, introducing new actions and messages that drive the narrative forward. Over time, you come to understand that you are building your own village. The game unfolds around three key aesthetics: discovery, narrative, and fantasy.

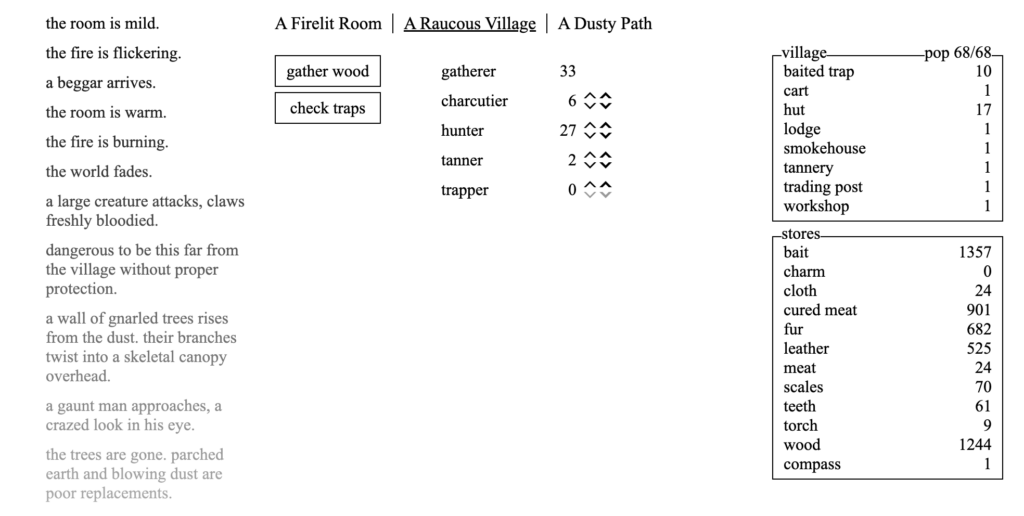

The discovery aspect is evident from the very first interaction. The “light fire” button is mysterious and invites the player to uncover more. As the game progresses, additional actions and interactions become available — more people join your village, new buildings are constructed, and deeper systems emerge. Discovery becomes the primary source of engagement. This is well illustrated by comparing the game’s beginning (Figure 1), which features a solitary firelit room and a silent forest, to a much later stage (Figure 2), where the village has grown to accommodate over 60 people and includes buildings such as a trading post, workshop, smokehouse, and tannery.

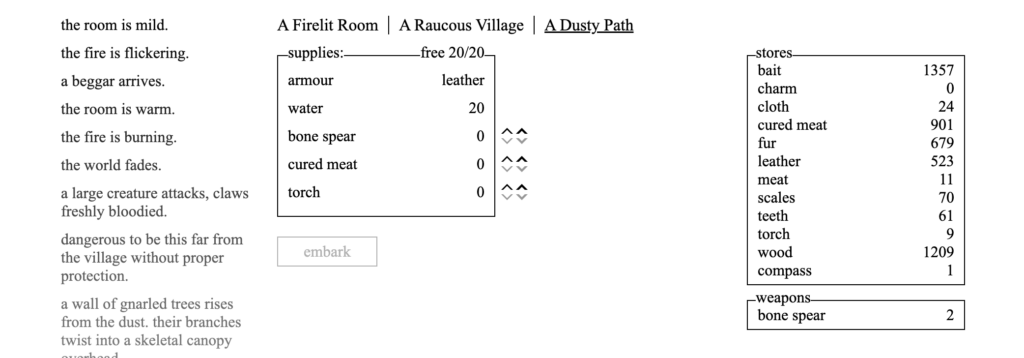

The second key aesthetic is narrative. The game invites the player into its world using only simple text, relying on imagination and patience. As you gather resources like wood, fur, and meat, and construct additional huts and shops, the unfolding story becomes increasingly engaging. A particularly compelling moment occurs when your village grows large enough to afford a compass (see Figure 3, and note the new “Dusty Path” tab). At this point, the game enters a new phase, allowing players to explore the surrounding environment. You now must prepare supplies — torches, water, cured meat — and, ideally, equip armor before venturing into the unknown.

The third and most striking aesthetic is fantasy. This becomes most apparent when you begin exploring the world beyond your village (see Figure 4). The player can discover caves, abandoned houses, and hostile creatures — evoking classic RPG dynamics. Figure 5 depicts a battle against a snarling beast encountered during one such exploration. Personally, this stage of the game reminded me of scenes from Skyrim, which served as my mental reference. It is remarkable how a game with such a simple presentation can evoke the atmosphere of a large-scale fantasy title.

Finally, it’s important to examine A Dark Room through the lens of accessibility. Thanks to its minimalist design, the game runs smoothly even on low-end computers or browsers with limited system resources. It requires only basic button clicks, with no need for quick reflexes or complex controls. The text is presented in a high-contrast black font on a white background, making it easy to read.

However, the minimalist approach has some drawbacks. The game could benefit from subtle use of color or minimal visuals — perhaps simple icons representing beasts or villagers — to enhance immersion. Additionally, it is currently only available in English, which limits accessibility for non-English speakers. The sound design is also extremely minimal; incorporating richer audio cues could further enhance the experience without compromising its aesthetic integrity.