The game I played was Tiny Room Story: Town Mystery (I’ll call it TRS for short), created by Kiary Games where players take on the role of a detective investigating their father’s mysterious disappearance in an eerily abandoned town. Available on iOS (and Android) for mystery and puzzle enthusiasts ages 4 and up, this mystery game highlights how narrative is woven into the architecture of a game setting, allowing players to explore the mystery story through spatial interaction.

Tiny Rooms operates on a relatively simple premise: players are presented with a series of interconnected room dioramas that they can rotate, zoom into, and interact with. Unlike traditional mystery games that rely heavily on dialogue or text exposition, TRS communicates directly through its spaces and architecture. The only dialogue you find comes from the detective at the bottom when you interact with the space or when you open the notes or mail on a laptop you log into.

Image 1: The investigator (you) saying the toolbox is too high for you to reach, highlighting the only real form of dialogue in this game.

TRS’ central narrative mechanic is its spatial interaction—tapping, sliding, using keys, and manipulating the environment itself. As the player, you are investigating what happened to the town; you’re snooping around, collecting information and cracking puzzles to learn more. When you discover a hidden key behind a book or decipher a code written on scattered notes, you aren’t merely solving puzzles—you are actively piecing together the narrative of the game. Each new breakthrough—each email or letter seen—allows the player to discover the narrative embedded into the setting. The intricate details of the spaces, from visible signs of struggle to rooms that have been thoroughly searched—reveals to the player more of the mysterious events that have taken place in the city of Redfield.

Image 2: The eerie atmosphere of the attic, which seems untouched compared to the rest of the house in chapter 1, shows that the player’s dad is definitely hiding something.

Additionally, the game makes it easier for players to solve puzzles and progress through chapters by preventing them from grabbing or interacting with items that have no relevance to solving any puzzle such as paintings, various files, and tools. The game’s inventory mechanic further reinforces this integration. Each collected item is a tool that helps the player progress the story. A worn photograph, a cryptic letter, or an antique locket—all serve as both functional puzzle elements and narrative artifacts. By making players interact with these narrative objects, the game allows the player to discover more about the narrative through these puzzle-solving mechanics.

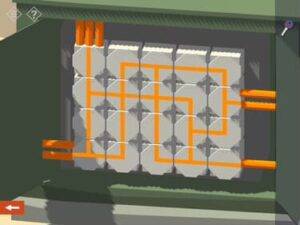

Image 3: The energy maze puzzle, which had to be done through collecting tools, makes the player wonder what happened and why some parts were hidden on the roof of the bank. What did the people want to hide?

The most fascinating aspect of TRS for me was how it employed spatial design as a storytelling mechanism. The architecture isn’t merely a backdrop; it’s an active narrator. The physical spaces tell stories through their arrangement, deterioration, and hidden elements. The room designs follow a familiar logic of storytelling: a scrambled desk indicates disruption, spoiled food hints at neglect and the passage of time. These architectural details create a narrative atmosphere that sets the deeply troubling, mysterious mood of the game.

Image 4: The dimly lit traffic control room with its spoiled fruits indicate that this place has been abandoned for some time, leading the player to wonder what has happened.

The player’s progression through TRS’ architecture further fuels the pacing of the story. In every level, the player tends to start in a seemingly ordinary space like a living room before picking up clues that reveal more disturbing details about the story such as a concealed drawer compartments or a hidden basement. These rather familiar spaces: houses, banks, churches—places most people would recognize—albeit looking a bit “roughed up” provides the player with a sense of surrealism; that there is more than meets the eye; that things are not as they seem. The eerie nature of each diorama—the fact that there is no one else in any of these spaces—sets a dark and mysterious atmosphere, making the player feel more immersed in the narrative environment of the game.

Image 5: Cracking the code to a hidden compartment inside a drawer, coupled with the investigator’s dialogue, further heightens the narrative of mystery in the game.

Unlike open-world mystery games where players might feel disconnected from the narrative environment due its vastness, Tiny Rooms forces you to observe every nook and cranny for potential clues. The player is the driving force of the story; they must pick up every clue, solve every puzzle, in order to progress the plot forward. The evocative and familiar spaces within the architecture of each room and space adds to the narrative of the game’s mystery, and coupled with the game’s soundtrack—a mix of James Bond-esque spy music with notes of 2000s detective shows—really allows the player to feel as if they were part of the narrative and mystery themselves.

Furthermore, the interconnectedness of rooms solidifies the immersive storytelling. It makes the narrative feel continuous rather than choppy. When players discover that a bookshelf in one room connects to a secret passage in another, they’re uncovering both a spatial and narrative story fragments, creating plot twists without dialogue. In that sense, TRS’ spatial architecture creates an atmosphere where the act of investigation feels organic and not forced. The embedded story with its various spaces and interactive elements creates a form of environmental storytelling that “shows” the player the narrative and not “tells.”

Ethics:

To be honest, I didn’t really find many accessibility features in this game outside of the “hints” to help players who were stuck. I think the most prominent accessibility issue in TRS is its heavy reliance on visual information. The core gameplay mechanic—identifying tiny objects in detailed diorama scenes—creates a strong accessibility barrier for players with visual impairments, making it hard for players who are visually impaired to immerse themselves into the game and its story and interact with the environment. I also felt the game had a bit of a cognitive accessibility barrier. Even while playing the game, I found myself often frustrated by how I wasn’t able to progress further in the story due to how hidden some clues were or how unintuitive some of the puzzles were. I remember spending half an hour trying to figure out a puzzle with the TV in chapter 1 before giving up and using a hint. The lack of an objective tracker, while maybe made to heighten the mystery component of the game, made it feel like an accessibility barrier for those who may have missed a small detail (but would get stuck for a long time).