WARNING: PORTAL 2 SPOILERS

This week, I grabbed a Nintendo Switch and loaded up Portal 2. Over the past couple of weeks, I’ve been revisiting a few beloved games that I haven’t played in years. Although I was playing a familiar game with new eyes, I think I’d like to branch out next time and try a game I haven’t played.

Valve released Portal 2 over a decade ago, a few years after the original game. It is available on Mac, PC, and console. I last played the game on a PC, and using the Nintendo Switch joysticks instead of a mouse definitely made movement and aiming much harder.

The game is rated E10+ for fantasy violence and mild language. While it may not be suitable for young kids, it’s not too difficult or mature for young adults. Portal 2, like the original Portal, has a single-player story mode, but the sequel introduced a two-player co-op mode for gamers who want to play together. I stuck with the story mode and played solo.

Narrative is a crucial part of this game, far more so than in the original title. Portal 2 took the story from Portal and ran with it, crafting a deep and engaging narrative that spanned a much longer game. That narrative is conveyed to the player in various ways, some more obvious than others.

The game carefully chooses when to limit the player’s actions. Through its mechanics and architecture, the game sometimes forces the player to encounter specific narrative elements. Other times, the game allows the player to explore where they otherwise shouldn’t be able to go. Those choices help control the game’s story while adding more mystery to the player’s experience.

One way the game limits the player is through forced action. At the start of the game, a robot named Wheatley believes you have brain damage and asks you to say “Apple.” Instead of speaking, the game only lets you jump. Similarly, there is a scene where Wheatley asks you to catch him, but the game disables the grab feature, forcing you to let him fall to the ground. The game treats these moments like choices — even though you didn’t have a choice — and they become part of Wheatley’s relationship with you. The “Apple” incident leads Wheatley to believe you do have brain damage for the rest of the game, and letting him fall ends up being a grudge he holds against you and references later on:

“We’ve had some times, haven’t we? Like that time I jumped off my management rail, not sure if I’d die or not when I did, and all you had to do was catch me? Annnd you didn’t. Did you? Ohhhh. You remember that? I remember that. I remember that all the time.“

We can look at these forced actions through the MDA framework. Mechanically, the game is preventing you from doing an action, but doing so creates a dynamic where the player is forced to make the wrong or unexpected choice. These false choices interact with the narrative in a deterministic way rather than letting the player choose how the story goes. This dynamic appeals to the Narrative aesthetic by inventing a clever way to force the story into a desired direction, ultimately giving the player the narrative experience that was intended.

Another limitation for the player comes from the game’s architecture and setting. In the first test chamber, you don’t have your portal gun yet, but debris is blocking all paths except the one that leads you to the gun.

The narrative requires that you find this gun, so the level is designed to force you to find it. This is an example of how architecture can function as a constraint, limiting where the player can go and forcing them to move in a particular direction.

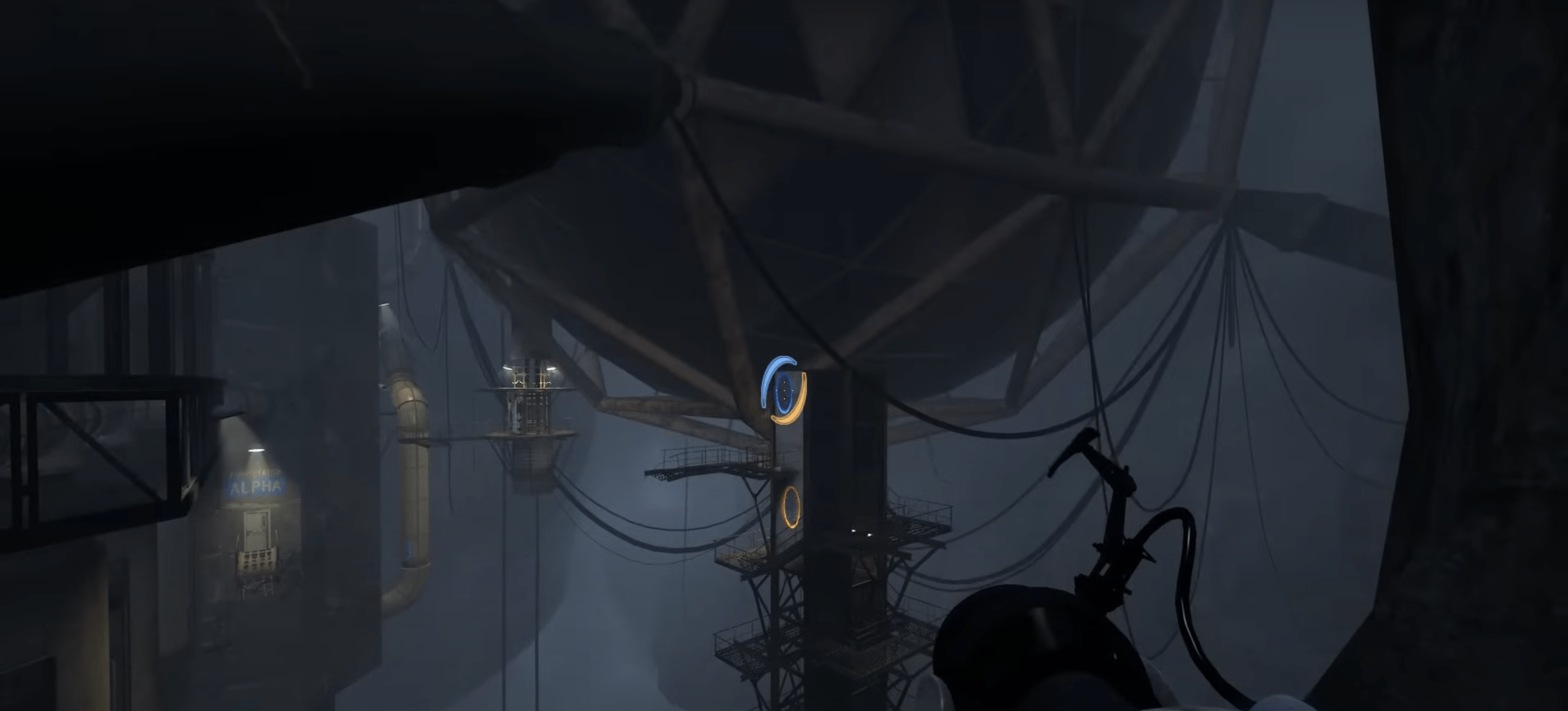

While limiting the player is an effective tool, removing limitations can also be effective. One such limitation that Portal 2 sometimes removes is the boundary of the playable area. In many puzzle games, the pieces of the puzzle are situated together in some defined space. However, there are rooms in Portal 2 that are so vast that you can’t see the opposite wall. Consider the reading about the functions of architecture in games. Rather than using this vastness as pure decoration, the game instead uses it to encourage exploration. The puzzles in these massive rooms are spread out, and players use the portal gun to warp back and forth, exploring the expansive space.

While solving the puzzle, the player also explores and appreciates the vastness of these old underground laboratories, which are a big part of the game’s backstory.

Another way the game loosens its physical boundaries is through easter eggs. Whether it’s an exposed tunnel or a broken wall panel, there are opportunities for the player to escape the boundaries of the test chamber and feel like they are scurrying around where they aren’t supposed to be. While it feels like the player has broken out of the game, these rooms were placed there intentionally, and they contain mysterious clues about a person who has been hiding in the walls of the testing facility. The rooms are physically in the game to create a sense of intrigue and mystery that adds to the game’s narrative elements.

The entrances to these rooms are great examples of affordances. When the player sees a broken panel, a slightly open door, or a metal grate off to the side, they know to look there in case there are secrets to be found.

So, Portal 2 is great at embedding its narrative into the game through mechanics and architecture. But, how much does that narrative impact the player’s experience? Using debris to force the player to find the portal gun actually results in the player getting a tool early on in the game. In contrast, Wheatley holding a grudge doesn’t really change how you play the game. To make sure that these story elements are more than just interesting dialogue or lore, I think the designers could have added more consequences to the forced actions I described. Imagine if, after you dropped Wheatley, he got mad and refused to open the secret panel, forcing you to find a way through the debris instead. The consequences of forcing the player into an action are currently only narrative, but they could actually impact the progression of the game as well.

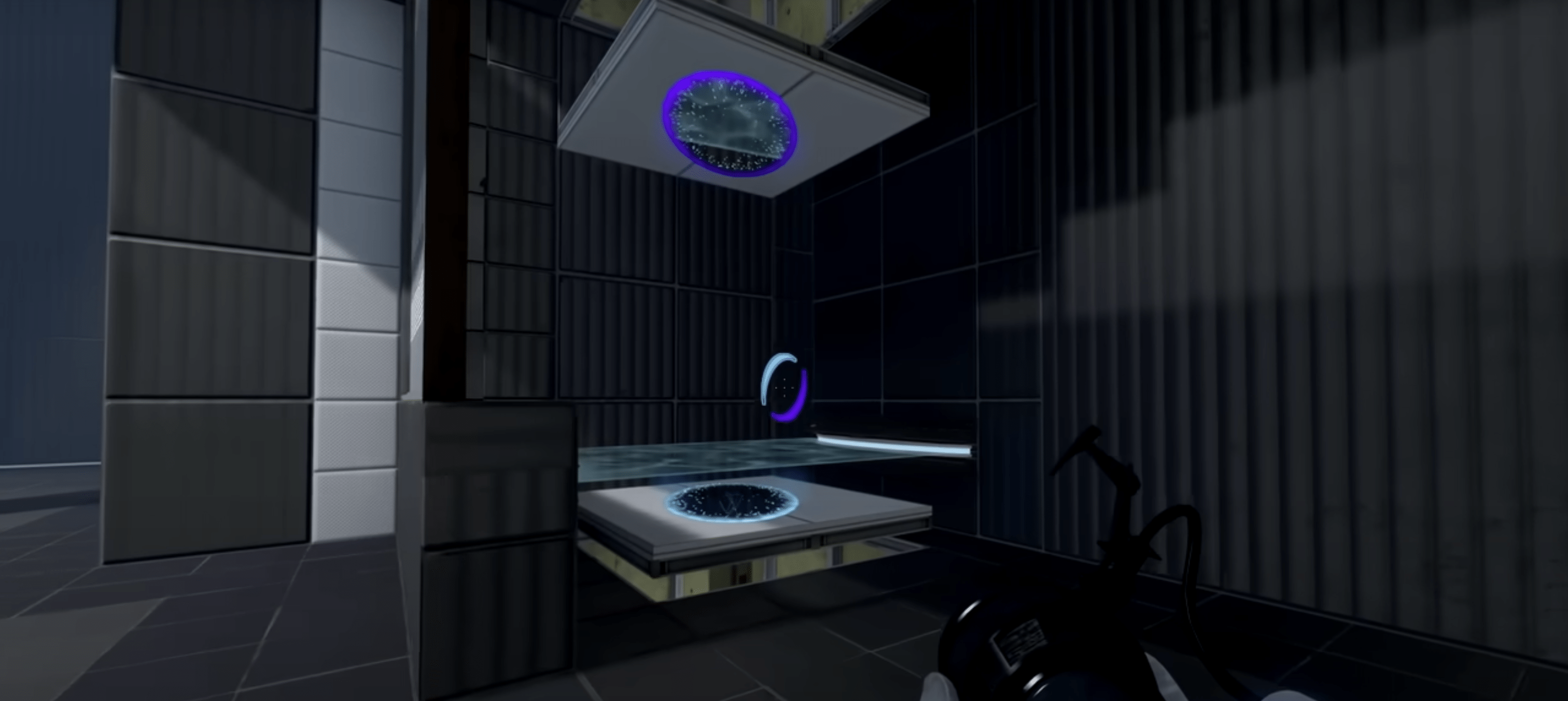

Since we’re on the topic of limitations, we should consider that some limitations don’t make the game better. In particular, games can have accessibility issues that limit how certain players interact with them. I have red-green color blindness, which means that I have a hard time discerning similar colors. In Portal 2, each player’s portal gun can make two portals at a time. When you open an additional portal, you must choose which of the first two you want to close. Colors are used to differentiate which portal is which and (in co-op mode) who created which portals. In the single-player version of the game, the player’s portals are colored blue and orange. In co-op mode, one player has blue portals while the other has orange portals; each player’s pair of portals looks more similar in co-op than in single-player.

Blue and orange are a high-contrast color pair that is easy to differentiate; light and dark blue are far more similar. While I didn’t get to play co-op during this playthrough, I don’t recall having any noticeable difficulty discerning the co-op portals from one another. Still, I know how factors like lighting and distance affect my ability to tell colors apart, so other players with more severe colorblindness could have some trouble in the later stages of co-op that take place underground. Unfortunately, there aren’t any color settings that allow you to change the color of the portals, though some modders have made it possible to change how portals look on the PC version.

In summary, limitations matter in games. When used correctly, they can be an effective game design tool, but neglecting the implications of certain limitations can hurt players’ experiences.

Unless otherwise specified, in-game images were taken from the following video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tx2JHttO0XY&t=5897s