Game: Yume Nikki (夢日記)

Creator: Kikiyama

Platform: Originally PC (RPG Maker 2003); also available on Steam and fan ports/emulations

Target Audience: Fans of psychological horror, surrealist storytelling, and players drawn to non-linear, introspective exploration. The game appeals to those seeking meaning-making through atmosphere rather than directive goals or action-driven gameplay.

Yume Nikki constructs a profound sense of nihilism not through shock or horror, but through the removal of traditional violence and goal-oriented systems. This non-violent design does not equate to a lack of interaction—instead, it functions as a void through which players must confront the symbolic meaninglessness of the dream world. Stripped of conventional plot, emotional arcs, and objectives, the game challenges the assumption that in-game actions must carry inherent significance, urging players instead to project their own anxieties onto the unsettling silence of the experience.

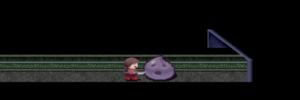

At the heart of Yume Nikki lies a radical reinterpretation of the relationship between mechanics and emotional response—a relationship that the game aggressively downplays in order to amplify an unexpected kind of affect. From a mechanics (M) perspective, the game features extremely minimal interaction. The player, controlling the silent protagonist Madotsuki, navigates fragmented dreamscapes, collecting “effects”—items such as a bicycle, knife, or frog costume—that may alter movement or appearance, but rarely serve any functional purpose.

There are no enemies to defeat, no traditional obstacles, no win/loss conditions, and almost no dialogue. Even the rare moments that suggest hostility—like being chased by the bird-headed Toriningen—do not result in death or reset, but in strange liminal imprisonment, again devoid of resolution or feedback.

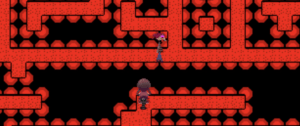

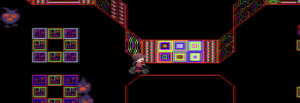

This hollow interactivity lays the groundwork for Yume Nikki’s dynamics (D)—the real-time unfolding of player experience. Gameplay is passive, directionless, and almost antagonistic to conventional engagement. There are no quests, no map, no instructions—only movement and observation. As players wander through these surreal, disconnected dream zones, a false promise of discovery hangs over the experience, hinting that meaning may emerge just around the corner. But the game rarely delivers. Instead, it reinforces the notion that you are not meant to understand—you are simply a ghost drifting through someone else’s mental terrain. The effect is not boredom, but emotional fatigue: a slow, creeping accumulation of unprocessed sensation.

All of this culminates in the game’s aesthetics (A)—the emotional resonance and experiential texture it creates. Yume Nikki does not aim to entertain or challenge; it seeks to dislocate and disquiet. What players receive in return for their effort is a feeling of profound alienation—what one might call existential dread. This dread stems not from what the game tells us, but from the structural refusal to tell us anything.

The game is littered with haunting symbols—broken classrooms, blood-soaked corridors, the infamous face of Uboa—but none are explained, contextualized, or resolved. Instead, their meaninglessness becomes the message. The player does not interpret the dream—they become trapped in it.

In contrast to games where violence provides emotional catharsis or narrative momentum (The Last of Us, Undertale), Yume Nikki even allows you to use a knife to “kill” NPCs—yet doing so has no consequence. No story changes, no score is tallied, no reward is granted. Killing is just another action. By denying players the typical feedback loop of cause and effect, the game casts doubt on the meaning of interaction itself. It’s no surprise that the 2018 remake, which introduced platforming and combat mechanics, was roundly rejected by fans—these additions reintroduced intent and consequence, effectively killing the emotional core of the original.

From a narrative design perspective, Yume Nikki embraces the Embedded Narrative mode described by Henry Jenkins. The story is not told—it is scattered, symbolic, and non-linear. It exists only in the player’s mind as they attempt to construct meaning from fragmented, dreamlike impressions. Compared to more curated walking simulators like What Remains of Edith Finch, Yume Nikki goes further, refusing even the comfort of emotional structure. In doing so, it creates a world that is hostile to interpretation, yet irresistibly absorbing in its strangeness.

If there is room for improvement, it might be in offering new players optional scaffolding—such as a togglable dream map or light-world glossary—without compromising the game’s commitment to emptiness. But perhaps that, too, would be missing the point: that Yume Nikki is not meant to be understood, only felt.