Warning: Contains massive spoilers for the game. This post is intended for those who have already played the game. If you haven’t, play the game first!

This week, I played Doki Doki Literature Club (DDLC), a game I’d held off on after being slightly spoiled on its true nature. Created by Team Salvato in 2017, DDLC is a psychological horror game disguised as a traditional slice-of-life visual novel (VN) dating simulator. It’s intended for ages 13+ and meant to attract VNs/dating simulator players into a subversive narrative engaging to a wider audience. It’s available on PC for free, but the 2021 paid DLC version (DDLC Plus) includes new content and expanded availability to consoles (Switch, PlayStation, and XBox). I played the itch.io free version. Through its subversions and applications aligning with Chess’s “Play Like a Feminist,” DDLC presents a narrative that may be overlooked or misunderstood by those unfamiliar with the VN genre; DDLC’s manipulation of players’ initial perceptions, showcases of false agency, and general anti-orgasmic structure strikingly impact the player, constructing a feminist narrative.

At its core, DDLC imitates a standard VN dating simulator: a school-aged male protagonist meets sexualized female characters whom he intends to court. This slice-of-life approach results in text-based enacted narrative—and often results in shallow, stereotypical representations of women, appealing to the male gaze. Early on, the main character chooses to join the Literature Club only because it’s filled with objectified women.

However, just as Chess notes oppression cannot operate in a vacuum, neither can DDLC; DDLC is best analyzed in comparison to the VN genre, mimicking their techniques and likeness to lure in a broader population and subvert their expectations. When analyzed through the lens of genre critique, Team Salvato emphasizes the genre’s issues, whilst simultaneously attracting its players to deliver a narrative they otherwise may not have discovered—similarly to how Chess describes gaming’s ability to act as “rabbit hole” into feminism.

To those beyond the target audience (VN enjoyers), one may perceive the game as boring or offensive, and quit before reaching its subversive elements. However, Team Salvato builds enough infrastructure for those accustomed to male-gaze-centered VN experiences to invest in characters and their (seemingly stereotypical) personalities, before shifting to horror elements—this includes but isn’t limited to problems such as mental health issues and abuse, which aren’t typically extensively portrayed in feel-good games of the critiqued genre. Thus, DDLC showcases adversities beyond the mainstream, a trait of feminist games.

Similarly, DDLC abuses players’ affinity for the VN genre by removing agency and denying players an orgasmic structure. Team Salvato includes genre-typical controls such as saving/loading and text skipping, inspiring players to reload and try “all choices.” However, players realize their choices have minimal impact, or that they simply have the illusion of choice, presenting false agency. As such, DDLC aligns with Chess’s concept of false agency as a feminist gaze which forces players to rethink their agency and surrounding world.

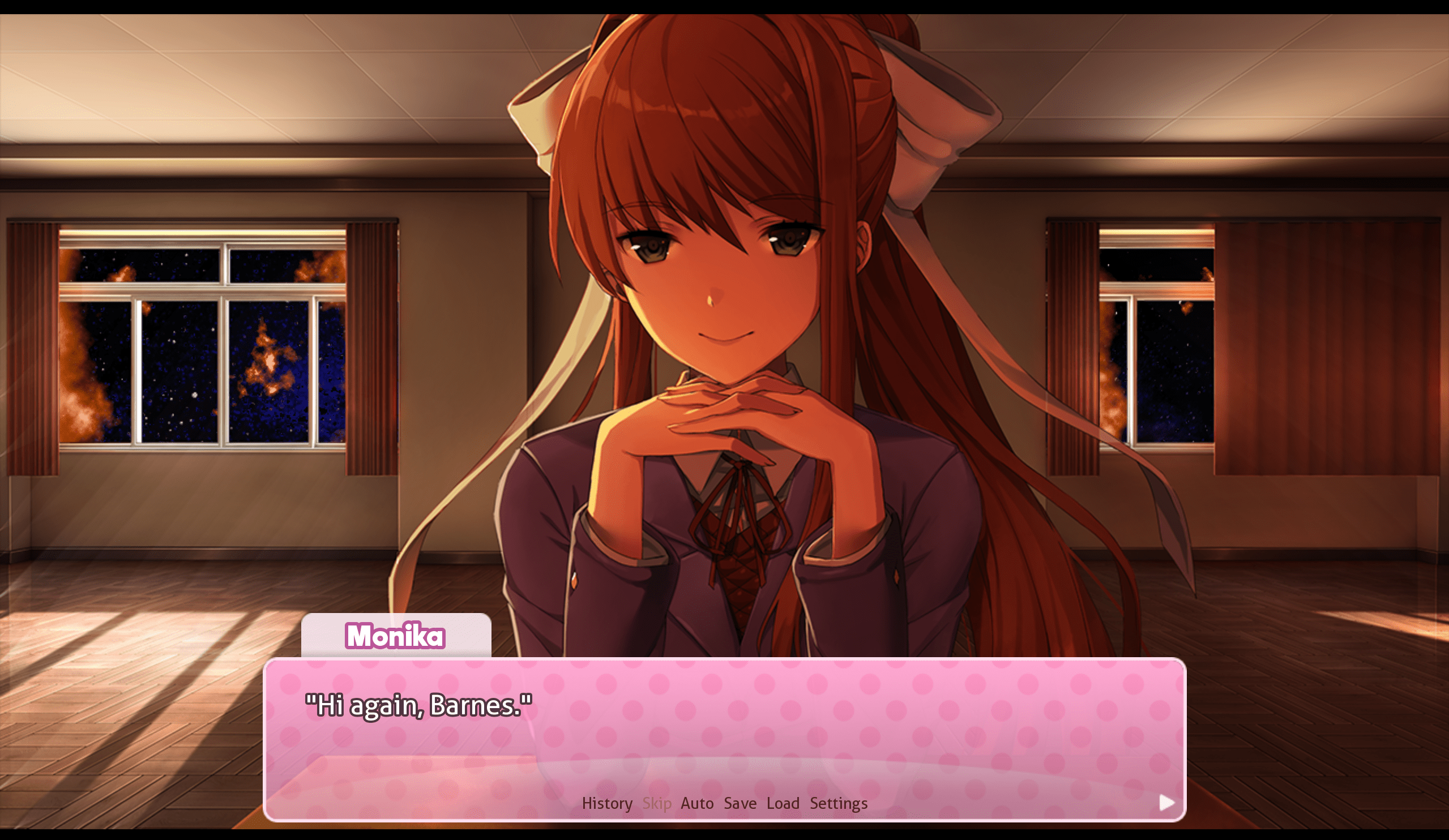

DDLC also constantly resets the game and deletes the player’s saves, once again applying false agency but also keeping the player in a long, subtle interaction loop; while there are orgasmic elements (notably suicides and the final conclusion), the majority of the game acts within the narrative middle, as the player cycles through interactions. This reappears near the end with just Monika, where the player faces seemingly endless conversation. While I will admit and critique how the game’s climactic scenes leave the largest impact, they act less as a linear narrative build-up and more like a sudden explosion out of the narrative middle, contributing to immense narrative and psychological impact.

Initially, DDLC appears to align with visual novel tropes, and can get labeled as male-gaze-centric; however, once one recognizes how the facade exists as genre critique, the game truly acts as a feminist game. By drawing in players familiar with the male gaze and introducing a new narrative filled with beyond-mainstream character traits and actions, denied/false player agency, and general anti-orgasmic structure, DDLC follows Chess’s ideas of what defines feminist games. While I did find the loop of resetting to eventually lose shock value, I cannot stress how the game—even despite slight spoilers—successfully left a psychological impact I’m uncertain could be recreated.

Discussion Question: How can one effectively attract those compliant with the male gaze to alter their perspective to be more critical of its existence?