‘One night, hot springs’ (ONHS) is an indie game by npckc. It follows the story of a young transgender woman named Haru as she navigates a night at the hot springs in Japan. Throughout, the game leverages and manipulates your agency over the story in clever ways to put the audience, as much as possible, in Haru’s shoes.

This is one major advantage of this story being told through the medium of the game. By choosing dialogue options, you’re forced, just as Haru is, to consider how people may react to you. Hovering over an option before selecting it, and in the brief delay before the next line of dialogue appears, you’re left in suspense, unsure how you will be perceived- just as Haru is.

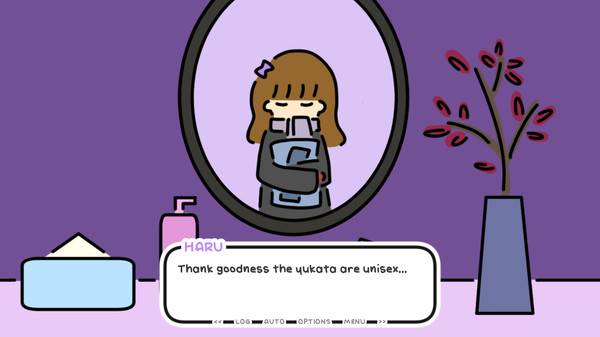

In between the moments of agency, the game’s writing is very strong. In fact, it stood out from the very beginning, when Haru searched for information on the internet about how to behave at a girl’s spa day. That little detail in and of itself lays bare the performative¹ nature of gender as something that must be learned: both through (often traumatic) social conditioning from a young age, as well as over time, in the constant human attempt to relate to others. For trans people, who are often excluded from the experiences that would otherwise teach them the norms and rituals of certain gendered activities, like a girl’s spa day, this experience is often more deliberate than usual.

This excellent writing also contributes to the impact of the choices you make. Every tiny detail of Haru’s discomfort, the frank discussion of Japan’s extreme restrictions on changes to an individual’s legal gender, and the occasional dismissive comment or unwelcome curiosity from your friends adds weight to the choices you make, as the player (if unfamiliar) slowly comes to grips with the weight on Haru’s shoulders, and must decide how to shoulder it.

The game world also responds to your choices such that your perception of reality, expressed through your choices, becomes a reality. If you regularly retreat into yourself, assuming people will be unkind, bigoted, or insensitive, you are locked off from the good experiences and connections with other characters you might have otherwise formed. On the other hand, if you assume the best in others and open up to them, you find over and over again that they are, at the very least, kind and well-intentioned. The hotel staff upgrades your room to ensure you can bathe in peace. A friend of a friend, while stumbling through a few inappropriate questions, ultimately helps you to visit the baths properly, and, later, to avoid an awkward encounter with your love interest’s boyfriend.

I think being a cisgender man substantially changed how I experienced this game, because, for the most part, I experienced these variations first. I was willing to select the dialogue options in which Haru stood up for herself or opened up to others. If I had negative lived experiences in the past doing the same, I might not have been so bold.

On a second playthrough, I was more timid. This was my way of playing the game as a feminist: to intentionally step out of the choices I would make, and place myself in a different way of thinking about the world, to see how the game responded. In so doing, I noticed another brilliant element in the game: three hearts in the top corner. Each time you give up or turn down a bid at connection, you lose a heart. But it isn’t quite so straightforward as ‘losing’ when your hearts disappear. Instead, losing hearts takes away agency. You become tired and withdrawn, unable to make the effort to keep going or talk about difficult subjects. For example, losing your first heart takes away your ability to select taking a shower when you return to the room (showers are often difficult for trans people who experience gender dysphoria). Keep going, and eventually, you shut down completely and decide to leave early. In this way, the game communicated to the player how feeling constantly uncomfortable and unwelcome can weigh you down and sap away your ability to do anything at all. Lose pride in yourself, lose hope, and you become a shell.

All these elements come together into a short, powerful experience that, by giving the player options (and sometimes taking them away), forces you to make some of the same choices trans people are forced to make every day.

¹ ‘Performative’ theories of gender are sometimes misconstrued as saying gender is a performance, i.e. fake and put on for show. Rather, performativity refers to an act that, in doing it, you also make it so, i.e. a judge saying ‘I sentence you.’ Gender is the same way: there is no gendered self behind the performance thereof, and by performing your gender, you are your gender.