Doki Doki Literature Club is an indie visual novel game developed by Team Salvato, available on Windows, Linux, and Mac. It follows the story of a student who joins their high school’s literature club and explores several romantic options with a twist. Though seemingly a dating simulator, Doki Doki Literature Club is actually a psychological thriller and is often considered a horror game. This game is suitable for ages 13+ due to potential disturbing scenes and triggering depictions for those who may easily be disturbed.

Doki Doki Literature Club attempts to provide a dating simulator experience that intertwines feminist theories by openly portraying the mental health issues that the four main girls — Natsuki, Yuri, Sayori, and Monika — are dealing with. The game developers aim to add depth to these characters, critiquing the typical way women are portrayed in manga and anime. Moreover, through the usage of aesthetic elements that are reminiscent of a horror game, such as glitchy text/visuals, as well as gory and disturbing imagery, the creators challenge the traditional cute and light-hearted aesthetic that the player first landed upon when starting the game—creating a harsh juxtaposition. However, despite this attempt, the game falls short of truly embodying feminist perspectives (perhaps because the creator is a white man); the girls are still characterized in a manner that lacks full characterization and proper portrayal of feminist agency. Furthermore, the limited game mechanics, clicking/pressing enter to continue, fosters a lack of control for the player where they are basically forced through a sequence of gameplay that emphasizes a sense of “disposability” between the girls. Thus, Doki Doki Literature Club bravely challenges certain notions of the traditional romance visual novel game, and the portrayal of women in this genre, with some commendable design choices, but one that isn’t enough as the approach the developers took lacks nuance and tastefulness.

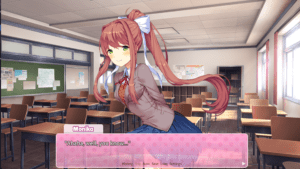

Doki Doki Literature Club starts off like how any other anime, manga, or dating simulator will portray women. The characters are designed in chibi style to emphasize cuteness, and they are equipped with suggestive school uniforms, as well as unnatural hair colors, playing into the pattern often seen in anime of over sexualization of young girls. Their demeanor is overly juvenile with scenes of some of the protagonists saying child-like phrases like “Meanie!” and their sprites are designed to show them making exaggerated cute gestures. These girls are characterized in a manner that lacks depth where each character fits a certain type of traditional personality archetype, with the presence of the “popular jack of all trades”, the quiet smart one, the “extroverted but shy in front of the person they like type,” and the childhood best friend.

In the game, all the four girls like the player. However, the portrayal of these girls’ romantic interests for the player lack a realistic depiction of love where there is agency, and subversion of stereotypes. Romance in Doki Doki Literature Club is programmed to have all characters like the player, and to be passive recipients of love rather than active agents, thus there is explicit reduced agency within the game; there is nothing the player can do to have the girls not like them somehow. Moreover, the girls are depicted to uphold the stereotype of women having no other goals than to find a man, and lacks characterization of the girls where we are learning about their individual ambitions, goals, and complexities. Additionally, a core dynamic of the game occurs when any of the girls die, and the game restarts. The existence of the girl that died disappears and any attempt from the player to mention them ca—uses scary consequences such as glitchy screens. Through this sneaky usage of looped arcs that actually layer on top of each other, the creators aim for emphasis of the horror aesthetic in the game. However, taking a feminist perspective, this actually undermines each girl’s struggles and the gravity of the issues that caused their demise. It feels like their life and their stories are being deleted, and a player isn’t given a chance to try and save them somehow, instead they have to move on to the next girl.

Discussion question: Do you think that embedding feminist views in a game through an over-exaggerated extreme approach is effective?