For this week’s critical play, I played Cascadia, a tile-placing board game published by Flatout Games. The target audience is players ten years and older who are interested in resource collection puzzle games. This game’s main strategy revolves around each player individually completing two main puzzles: habitat expansion and animal arrangement. By making players each take their additions to their board from the same pile as other players and creating a puzzle with so many different solutions, the designers of Cascadia have created a competitive puzzle game that tests players’ creativity and flexibility.

Different Puzzles, Same Pieces

In Cascadia, players build their boards in front of them as the game progresses, taking pairs of one animal and one tile each turn to arrange them to maximize their points at the end of the game. Because every player is taking an animal and a habitat tile from the same pool of pieces in the middle (Figure 1), players are each completing a puzzle in a situation where they share potential pieces to that puzzle with other players. In our game of Cascadia, I needed one more fish to complete a run of five, which would award me with 6 extra points (Figure 2).

Unfortunately, every other player was in the same boat as me, waiting desperately for any fish to appear in the pool of potential animals in the next turn to increase the length of their salmon run. This mechanic makes the animal arrangement puzzle significantly more difficult, introducing an unnecessary but engaging obstacle for other players. The game is already balanced against allowing any player to receive a major advantage, given the significant role chance plays in the collection of pieces. When players have similar goals, the luckier one ultimately takes a critical piece of the puzzle from another player. Over time, this game-balancing choice results in players progressing through their board at roughly the same rate. This dynamic cements the game’s fellowship and caters to players’ psychogenic needs for power by allowing them to deprive others of their need for materialism. The completion of the puzzle thus becomes opportunistic, with most of its difficulty arising from the player needing to adapt to situations where they may be deprived of the tiles and animals they need. The result is a game where players must be cognizant that completing any given puzzle largely relies on other players and chance as much as skill.

However, to facilitate this interaction between players, where a key puzzle piece could be taken at any moment, the game simplifies its dual-puzzle system so much that much of the challenge becomes lost in favor of fellowship. Additionally, interaction between players is stifled because of the complexity of the tile arrangement, which, even simplified, is too complex and requires the player to hold too much in their working memory to form a strategy effectively. Imagine tracking a board like the one below but for five other players in addition to yourself (Figure 3).

As a result, the game is not difficult enough to present a satisfying puzzle but is too complicated to facilitate meaningful anti-fellowship between players. To increase the puzzle’s difficulty and instill more conflict between players, the game could allow for sabotage or complex interactions between players, like stealing tiles or blocking animal placements. This would improve the challenge and fellowship of the game as players interact beyond simply taking from a collective pool of pieces. Multiple player profiles, like the “killer,” would be catered to with this option, and the puzzle itself would be completed against an antagonistic force, increasing the ingenuity required to solve it optimally and, thus, satisfaction. However, this choice would ultimately sacrifice fulfilling the need for materialism and achievement since some players would never complete any of the puzzles in front of them satisfyingly. So, if the game designers are satisfied with a single fellowship mechanic and a mostly individual experience of building a puzzle with little regard for the actions of others, their current mechanics work excellently to give a sense of achievement and let players earn points even if their puzzles don’t have the “perfect” solution.

Creative Solutions

Because the pieces that a player can add to their board depend on the actions of other players and the luck of the draw, the “solution” to each player’s habitat and animal arrangement puzzle results from the player’s ability to adapt to a changing landscape. This manifested in my own playthrough, where I was left with a board that looked like the one to the right (Figure 4) while I waited for more hawks, a fish, or a bear.

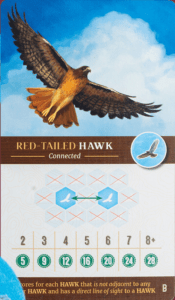

Any of these combinations would increase my point total, leaving me with a “completed” puzzle. Still, the unpredictability of the game made it essential to have backup plans and secondary objectives to fulfill the final goal, which was arranging my pieces better than other players. In this case, I left spaces for more fish, bears, and hawks, each an arc-in-progress that could be advanced by prioritizing them on any given acquisition loop on my turn. Making the puzzle dynamic with pieces that appear at unpredictable times makes players take on a flexible and creative playstyle since one might have to change their strategy on the spot to win. This creativity ultimately relies on interaction loops, where a player will take a new tile and animal and place them on each turn. The game ultimately uses each loop on one’s turn to fulfill five different arcs, illustrated by the possible arrangements of animals (Figure 5), which decide the final winner: the creator of the best-solved puzzle.

Except for extremely fortunate games, players must choose from several arcs to complete, leaving some incomplete in the process. The winner ultimately is the person with the most completed arcs and, therefore, the most complete animal arrangements. Each animal selection loop updates the player’s mental model as they get closer to completing any given arc. Once an animal is placed, the player receives feedback in the form of the current state of their board. These short, frequent loops do an excellent job of teaching the player to think on their feet when it comes to placement, and each animal arc delivers a success story as the player collects each of the required tiles arranged perfectly to receive their point reward.

While this approach to puzzle-solving promotes player problem-solving and adaptability, it can leave players feeling unaccomplished with their psychogenic need for achievement unfulfilled as they have to abandon strategies in favor of completing other arcs. To create a sense of accomplishment more in line with traditional puzzles with a single solution, the game could require every player to achieve a certain number of points before other players do as the win condition, rather than ending when the cards run out.

This ensures that at least one player feels they have completed the puzzle most efficiently while encouraging other players to aim for complete arcs instead of advancing partial solutions. This would undoubtedly increase fellowship and require more intellectual involvement as other players aim to complete their puzzles before other players instead of placing tiles down randomly to brute force the puzzle. This change would make the game more strategic at the cost of player autonomy. Strategies would likely become more optimized to complete the shortest arcs possible in the least amount of loops, which would ultimately interfere with the game’s balancing as other arcs, like the hawks to the left (Figure 6), fall to the wayside. This change would ultimately harm the game’s key aesthetics of creativity, adaptability, and challenge in exchange for letting players aim for completion over “best fit” playstyles.