Secret Hilter is a unilateral competition game in which one team of Liberals competes against a team of Fascists in order to pass acts. The game was originally created by the game publisher Goat, Wolf, & Cabbage, but can be easily reproduced using simple playing cards. The target audience of Secret Hitler is young adults. Secret Hitler is successful in establishing fellowship (and also suspicion) between players by the use of hidden information and encouraged deception.

The game is structured in rounds in which one rotating player, who is called the president that round, chooses a chancellor for the round to help them enact an act. Based on the president’s choice of chancellor, the rest of the players can vote on whether or not they want to let the pair enact an act. The act can either be a liberal act or a fascist act. Liberals want to pass liberal acts, and Fascists want to pass fascist acts. When I was playing the game, this vote often resulted in players “campaigning” for themselves or other players and guilt tripping other players.

The fun in this game comes in that players often do not know what team their fellow players are on. Most of the players are Liberals, but a small subset are Fascists. One of these Fascists takes on the special role of Hitler. The Fascists know who all are on their team, with the exception of Hilter, who does not know who the rest of the Fascists are. However, the Liberals do not know who the Fascists, Hitler, or their fellow Liberals are. They only know their own role. The game is zero-sum in that each team either wins or loses, but there are multiple ways of doing this. Liberals can either pass a certain number of liberal acts (which depends on the number of players) or assassinate Hitler. And the Fascists can either pass a certain number of fascist acts or get Hitler elected as chancellor in order to win.

One of the main opportunities for deception and confusion in this game is in the mechanics in how acts are enacted. The president of that round draws three cards, each of which could be either a fascist or liberal act card. They then pick two of these cards to hand to the chancellor they chose. And the chancellor can choose which of the two cards to enact. However the rest of the players do not get to see if the cards the chancellor chose from were liberal or fascist, nor do they get to see the card that the president discarded. The president and chancellor can try to convince their fellow players of what they were given, and what they say may contradict. In my experience playing the game, this moment in the game often resulted in all of the players talking over each other to a point of complete confusion.

The runtime dynamics of this game are mainly based on the opportunity for deception and accusation within the formal elements of the game. For example, players may lie about why they voted to let a certain chancellor enact an act. This deception is intensified by the unique historical premise of the game. The game is based on the Fascist reign of Hilter and is ultimately a collective effort to differentiate between Fascists and Liberals, or good versus evil. Although this premise can be off-putting to some, in many social settings it adds a level of humor to the gameplay experience. The players on the fascist team immediately see themselves as “evil” at the start of the game. This breakdown of values often makes lying easier for these players. It’s inherent to their position in the game. Similarly, the liberal team immediately desires fellowship with their teammates in the fight against evil, even if they don’t know who these teammates are. This combination of player mentalities means that trust is hard to come by, and often the most vocal players are the most successful.

Overall, the combination of the formal and dramatic elements of this game create fun based on fellowship and (often) contrived narrative. Players must prove to their fellow players that they are trustworthy and liberal, while acting in a manner that brings whatever side they truly are on closer to victory. This process also often involves generating a narrative behind the gameplay. For example, when I played with my friends, we came up with specific liberal or fascist acts to enact. This added another level of humor to our gameplay, as crude as it often was.

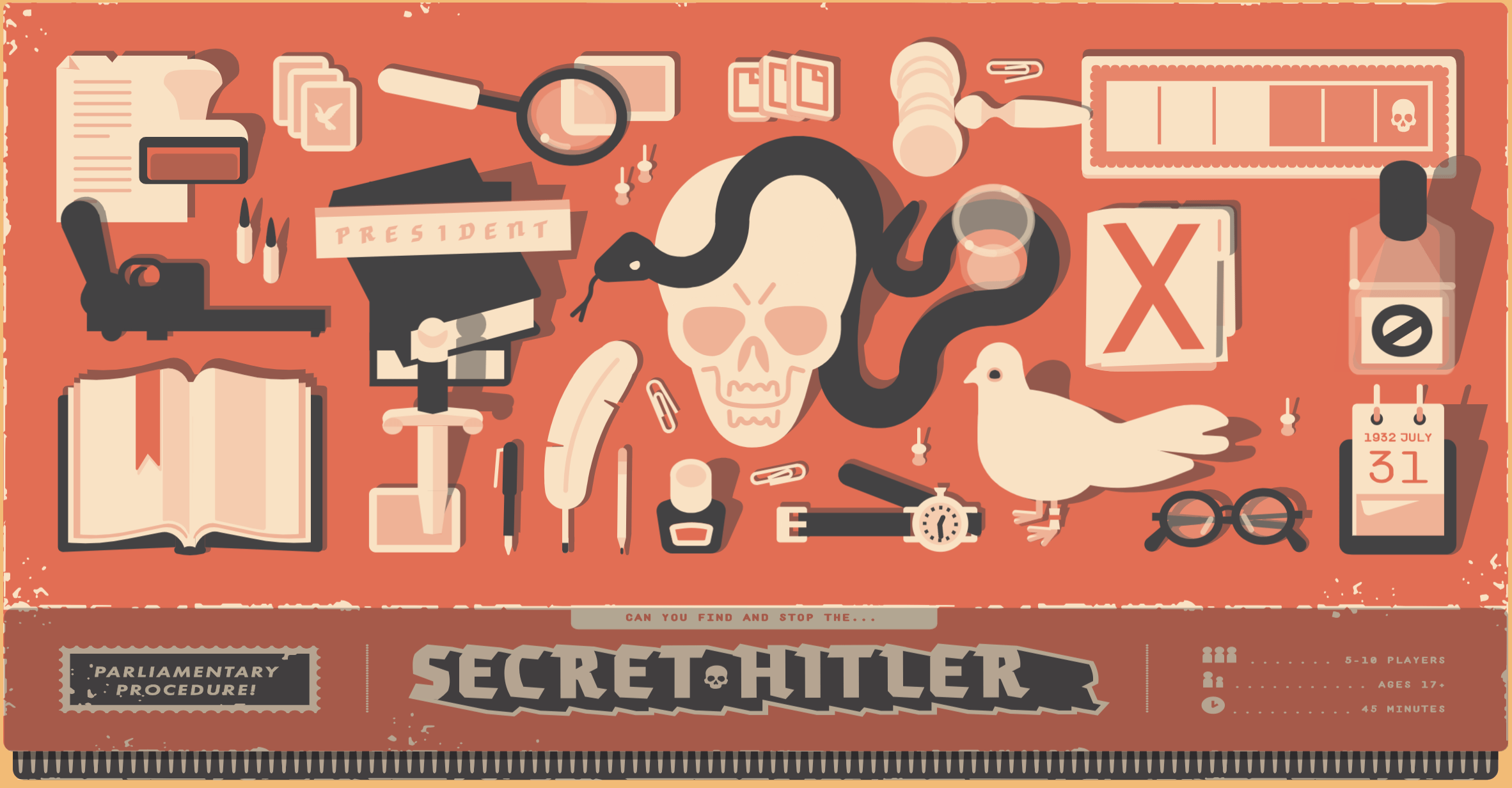

(image from secrethitler.com)