- Identify the basic elements in a game of your choice (actions, goals, rules, objects, playspace, players).

One of my favorite games is Neko Atsume, which is a very low-stakes single-player cat collecting mobile game. The main actions are to buy/place food and goodies to attract cats to your yard, collect fish and mementos from cats as they visit, and then take photos of cats to fill in the Catbook. The playspace is a yard, which is divided into different slots to place items.

[Image of Neko Atsume yard, showing where different food and items are placed. ]

The core goal of the game is to attract cats to complete the Catbook, and then collect all of their mementos. The secondary goals might be to optimize the fish income, decorate the yard with different skins and customizations, and photograph cats in all of the backgrounds and poses.

The objects of the game include: food, toys or “goodies,” yard skins, fish currency, catbook, mementos, and a camera/photos.

The rules of the game primarily dictate how cats visit:

- Cats visit only while you’re away and food must be out to attract them

- Each cat has item/food preferences, and items have designated occupancy limits

- The yard has limited inside and outside spots that influence how often cats visit

- Food and goodies must be purchased with fish

2. As a thought experiment, swap one element between two games: a single rule, one action, the goal, or the playspace. Imagine how the play experience would change based on this swap.

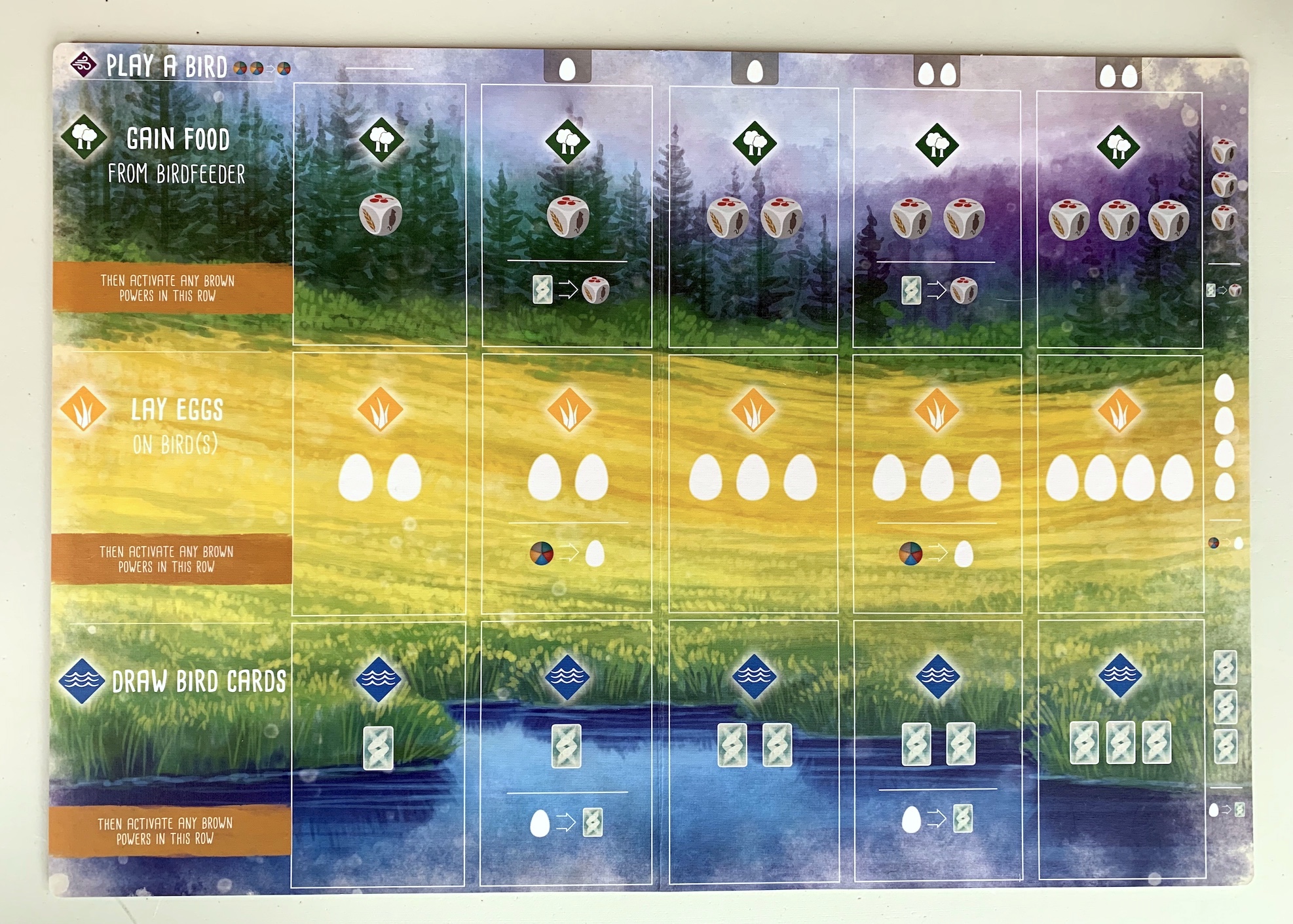

Thinking about Wingspan and the game Parks, I think it would be really interesting to see the playspaces swapped, where Parks becomes separated into different environments and Wingspan progresses along one trail.

[Image of Wingspan player board, showcasing the different ecosystems where birds can be placed.]

For Parks, the gameplay might shift from being a competitive and linear style to a more casual game with the player being more focused on resource gathering from different ecosystems and perhaps needing certain gear to visit parks in different environments. With this change, there would be less direct interaction and more of a need to plan how you navigate the trail in the right order.

[Image of Parks game board, where players move forward on a linear trail .]

Moreover, it would be interesting to see Wingspan progress on one trail but keeping it on individual boards, so that players have to think about where to place their birds more carefully and place more weight on the goals like round bonuses and bird powers that activate multiple times.

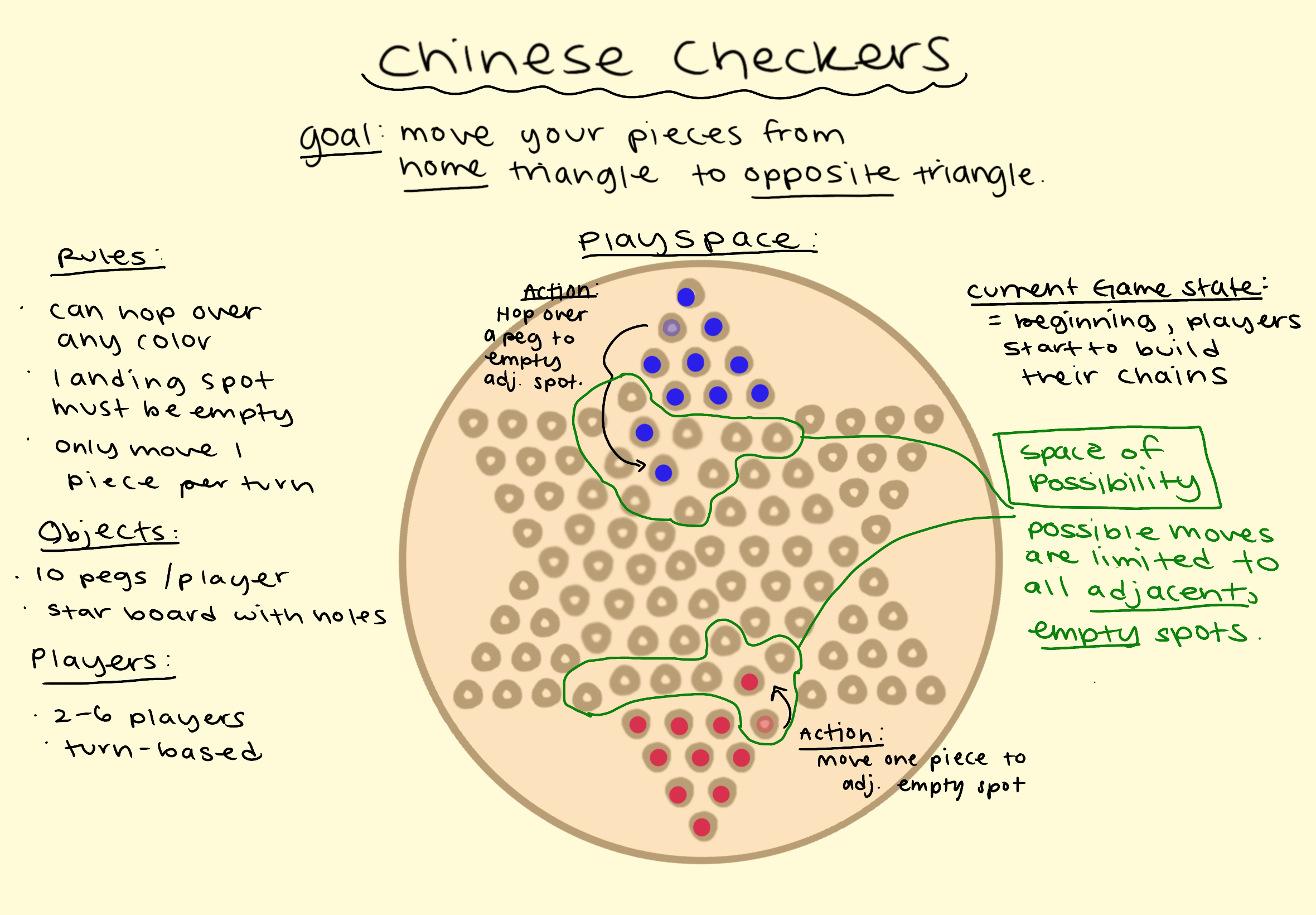

3. Pick a simple game you played as a child. Try to map out its space of possibility, taking into account the goals, actions, objects, rules, and playspace as the parameters inside of which you played the game.

Here is my visual map of chinese checkers:

4. Pick a real-time game and a turn-based game. Observe people playing each. Make a log of all the game states for each game. After you have created the game state logs, review them to see how they show the game’s space of possibility and how the basic elements interact.

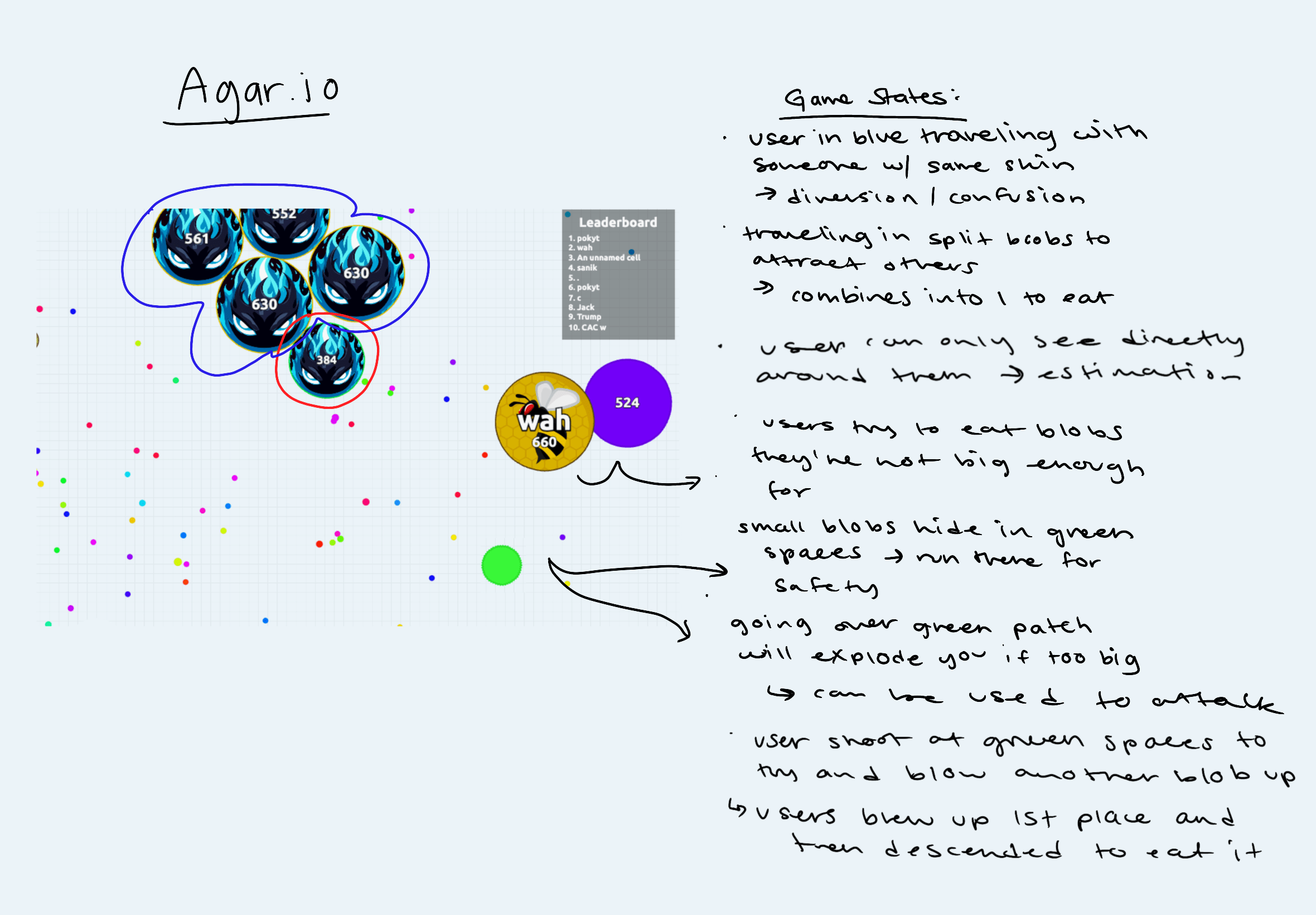

For real-time game, I spectated Agar.io, which is a multiplayer online game that allows you to move around as a blob and eat other player’s blobs. The main goal is to grow by eating smaller pellets and other player blobs, while avoiding being eaten. My logs are depicted below:

[Image of Agari.io screen and different game states and other notes.]

After reviewing, I found that the states map out the game’s space of possibility as they demonstrate how even with limited actions and simple rules, there are a lot of strategic approaches to the game. For example, at any time players can choose to hide under green patches, or go on the offense and chase other players. Alternatively you can choose to be more passive and play it safe by slowly farming the free pellets without interacting with anyone else. Players can also split to move faster and secure eating someone, but that comes with a tradeoff since smaller split blobs are easier for others to eat until they recombine. The logs I kept show how these choices and the spaces of possibility constantly shift as the player’s size, position, and surroundings change.

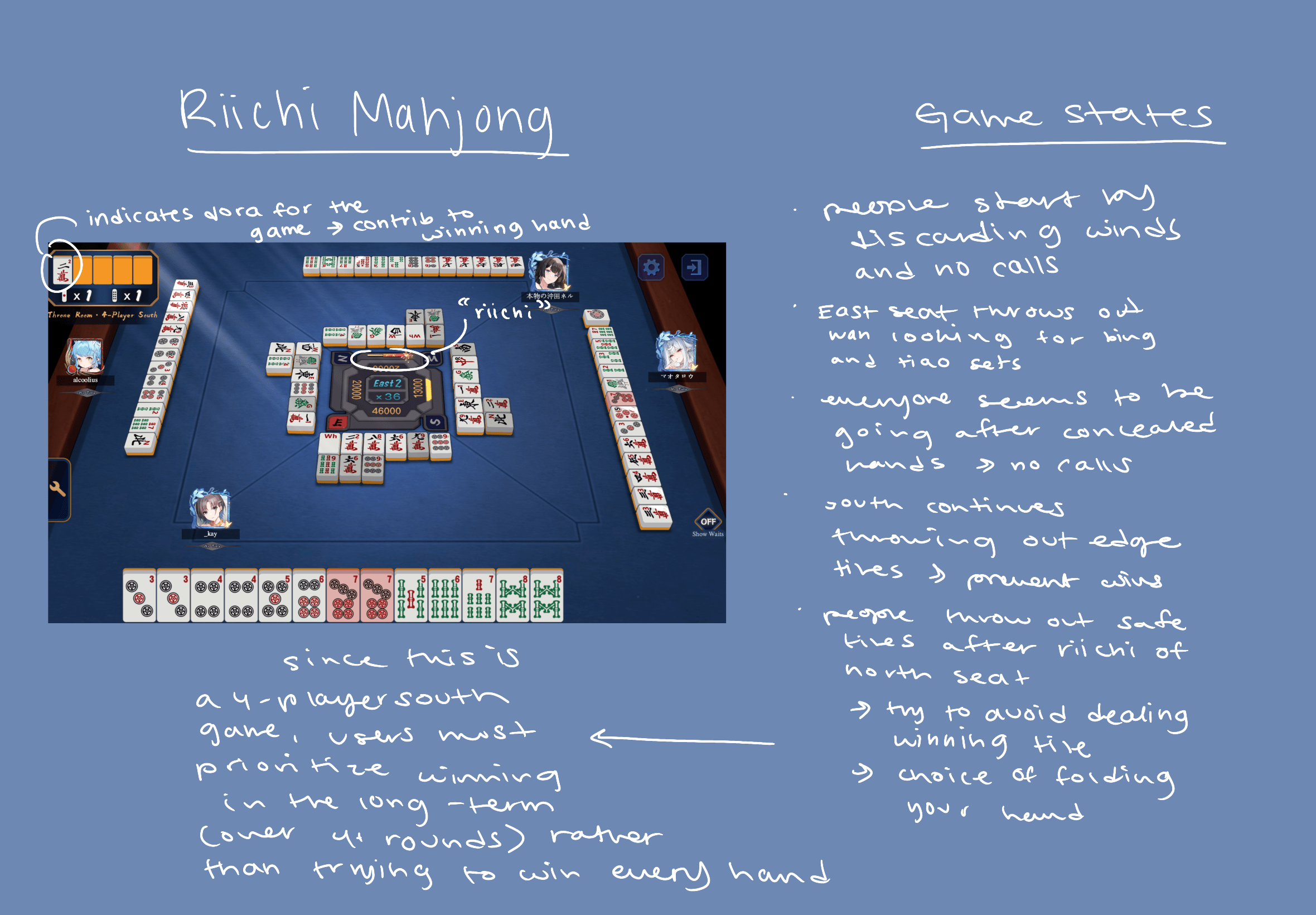

For the turn-based game, I spectated a Riichi Mahjong game in MahjongSoul. Unlike Agar.io, which is continuous, this game progresses in turns where each player draws one tile, discards one tile, and sometimes has the option to call another player’s discard to complete a set. The aim is to build a complete winning hand, and along the way, each decision reshapes both your own options and the risks you present to others. There is a visible pool of discarded tiles that essentially give constant information about what opponents are collecting

[Image of Mahjong screen with 4 players, showing each of their hands and the tiles they’ve played in the center.]

Watching these interactions showed a very different kind of space of possibility that is shaped by the changing information on the table, which influences probabilities of getting certain tiles, risks of giving someone a winning tile, as well as commitments to winning hands. For example, sometimes you can have your hand open, which limits your ability to choose certain tiles and hands, alternatively you may “riichi” and commit to being one tile away from winning to add pressure to other players.

All in all, I think these games show how designing both real-time and turn-based games is a second-order design practice, since as a designer you may create very different spaces of possibility that influence the experiences of players, but ultimately the game is made by players experimenting with unique strategies and plays.