dys4ia, created by Anna Anthropy—a prolific game designer, writer, and educator—invites players into a deeply personal narrative chronicling her experience as a trans woman undergoing hormone replacement therapy. While often mislabeled as an “educational” or “empathy” game for cisgender audiences, dys4ia’s true target audience is other trans people who might recognize themselves in its fragmented scenes and gain a sense of power from its mechanics. This focus on lived experience sets dys4ia apart from many of its genre peers, such as Gone Home or Life is Strange, which, while praised for their queer narratives, primarily invite cisgender or non-queer players to empathize with marginalized characters rather than centering the marginalized audience themselves.

I played dys4ia as a downloadable executable on my Mac, which required some troubleshooting and the use of the Whisky emulator. This experience highlighted a key barrier: although the game is free, its platform can be intimidating or inaccessible, especially for those less comfortable with technology. As Chess informs us, feminist games available “are not always accessible or properly distributed in a way that can be played widely,” limiting their reach, feminists ability to “play as protest,” and potential to disrupt the current video game industry. Chess notes that players need “time, resources, and other accommodations in order to protest.” Yet dys4ia’s distribution raises an additional concern: making play more accessible requires making game publication more accessible for feminist game designers.

To play dys4ia as a feminist is recognize it as a tool for feeling, becoming, and rethinking (Chess) the lived experiences of trans women, illustrating the potential for game design to foster empathy and critique power.

By embedding scenes of medical gatekeeping into its narrative, dys4ia critiques how medical institutions wield power to create barriers for trans women and multiply-marginalized people seeking healthcare, inviting players to feel and rethink the injustice of systems that Chess argues “routinely fail marginalized people.”

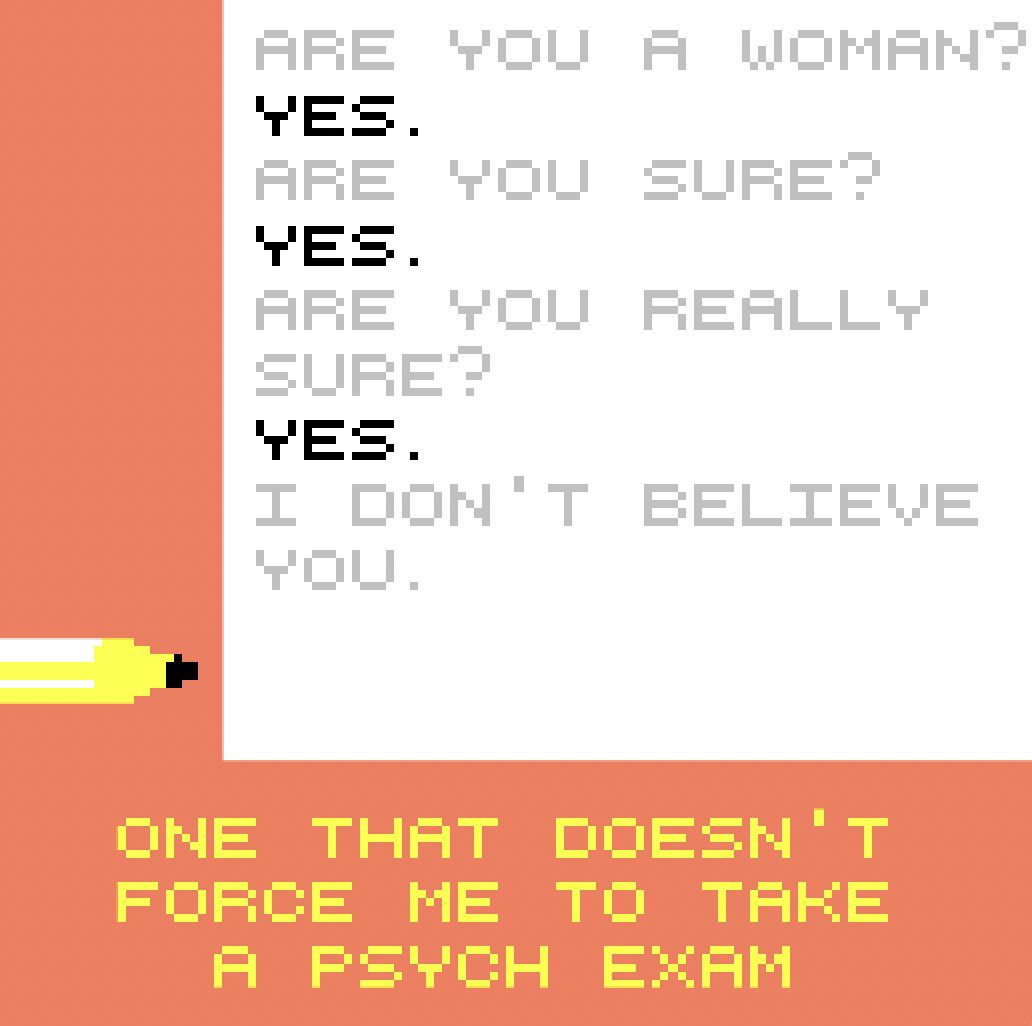

For example, in level 2, the player must experience the protagonist being forced to take a psych exam by a clinic before receiving hormone replacement therapy (HRT). The exam consists of impersonal, redundant questions, exhibiting the arbitrary “criteria” that trans people face and highlighting how the process is more about expressing doubt than gathering information. Medical providers often use these psych exams as gatekeeping tools, denying care to patients who don’t meet said subjective criteria. The exam then culminates in a dismissive statement— “I don’t believe you”— rather than what should be a final question. This demonstrates how the psych exam serves primarily to discourage trans women from transitioning, reflecting the clinic’s inherent skepticism of the protagonist’s gender identity. The game’s depiction of the exam begs players to “rethink” the use of pysch exams in seeking gender-affirming care, especially since these exams stem from an era when being transgender was wrongly classified as a mental disorder. This aligns with Chess’ argument that games can be tools for “rethinking” dominant systems and issues of injustice.

Notably, the game’s mechanics force players to repeatedly click through impersonal, redundant questions. This creates what Chess calls a “never-ending narrative middle,” simulating the frustrating and drawn-out process trans people face when seeking gender-affirming care. By rejecting a climax-centric narrative structure, the game embraces what Chess calls “the pleasure of delay,” realizing its “queer and feminist potential” as a tool for “feeling and increasing empathy.” In contrast, many narrative-driven games (Night in the Woods or Life is Strange) still adhere to more traditional story arcs, even as they explore queer or marginalized experiences. Hence, dys4ia’s embrace of delay is a radical formal choice within its genre. Furthermore, this repetitive mechanic forces players to witness the invalidation, stigma, and trauma of medical gatekeeping, achieving Chess’s vision of games as spaces where players can “think within different perspectives and experiences.”

As Anna disclaims at the beginning of the game, dys4ia “is not meant to be representative of every trans person,” nor do I think it should feel beheld to this impossible task.

Nonetheless, if we are to play dys4ia like a feminist, we should consider how the game “can be improved by looking at broader problems.” In particular, the game poses many opportunities to touch on broader, intersectional issues, such as medical racism, classism, healthcare inaccessibility, and so on.

For example, in the waiting room scene, we could illustrate medical racism by showing patients of color experiencing longer wait times and being passed over while other patients receive prompt attention. This would be important to prototype as Chess argues that “feminists should not think about gender difference as separate from ethnicity, sexuality, or social class;” however, we would want to represent this intersectionality in such a way that doesn’t reduce these complex experiences to simplified game mechanics, avoiding what Chess critiques as “shallow” or “reductive” representations. To prototype this improvement effectively, we would create a role prototype since we’d be “providing a new functionality for users”: demonstrating how racial bias and transphobia interact in healthcare settings. The features needed to support this role would include:

- coloring the patients in with different skin tones

- when the protagonist’s waiting time is up, add a thought bubble to one of the patients of color with the words “they came in after me… ” or “why have I been waiting so long?”

I predict that allowing players to witness multiple intersectional perspectives would increase empathy and understanding since it’s an additional opportunity for players to “think within different perspectives and experiences,” but we’d need to carefully balance this against the risk of overwhelming players or diluting the game’s core message about trans experiences

By evolving the game’s mechanics to transform the player’s agency, dys4ia serves as an agentic-training tool that embodies Chess’s concept of “becoming,” allowing players to experience how trans women navigate, resist, and ultimately find power within oppressive systems.

For instance, in level 1 the player encounters a scene titled “these feminists don’t accept me as a woman,” where hostile words from so-called “feminists” (colored pink, bearing the male symbol) injure the player (colored blue). This visually and mechanically reinforces the pain of exclusion from spaces that should offer solidarity. The alignment of color and symbol is a clever design choice, with the player’s blue color reflecting how others perceive them pre-HRT (as a man), while the pink “feminists” wield patriarchal violence despite claiming womanhood.

In level 4, this scene returns, now titled “these dumb bitches still say I’m a man.” This time, the mechanics shift: the player (now colored pink post-HRT) is no longer harmed by the words. Instead, these words— still carrying the male symbol but now colored blue— are deflected and bounced back by the player. Upon impact, the words transform, turning pink and their symbol shifting to female. This design choice does more than signal resilience; it dramatizes a process of agentic transformation. Through actively engaging with the mechanics, the player experiences what Chess describes as agency: “the will to act and gain voice within systems of power.” Having navigated repeated assaults on their identity, the player now possesses the power to resist and reframe hostile rhetoric, reclaiming agency and re-inscribing meaning.

Through these evolving mechanics, dys4ia becomes what Chess calls an “agentic-training tool.” The game teaches players to “reconsider their own agency against systemically oppressive structures, and create action, meaning, and motion out of them.” The shifting colors and symbols reveal how gender categories can be disrupted and reclaimed, while the mechanical shift from passivity to active resistance demonstrates how marginalized people can cultivate power within oppressive systems.

These dynamics become especially powerful considering that dys4ia’s primary audience is other trans people. Rather than centering a cisgender gaze or seeking to educate outsiders, the game creates a space for trans players to see their struggles, frustrations, and triumphs reflected and validated. As Chess argues, in games, agency can “exceed the boundaries of the game itself.” These evolving mechanics thus create a resonant, agentic training ground where trans players can rehearse resistance and transformation in the face of real-world exclusion and hostility.