Content warning: suicide, self-harm, dark topics generally. (Note: not going to include some of the more graphic/triggering images.)

This week, I playtested Doki Doki Literature Club, a visual novel video game developed by Team Salvato, headed by Dan Salvato, originally available on macOS and Windows and first distributed through itch.io, then later became available on Steam. DDLC has since (the Plus version) expanded to other platforms, such as Switch, Playstation, and Xbox. I playtested the game on Steam.

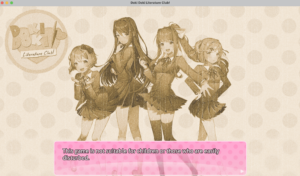

At the beginning of the game, the game issues a warning that the game is not suitable for children under 13 or people who are easily disturbed.

Figure 1: Mild content warning at start of the game

For context, I (maybe fortunately in terms of mental health, maybe unfortunately in terms of game experience) did not go into DDLC blind; around the time DDLC came out, it quickly gained popularity, and I had somehow heard about the game (I would’ve been around 12 at the time.) Far too scared to actually deal with anything horror, I had actually gotten my cousin, who would’ve been around 17 at the time, to play it. He went in blind, and at the end of the game, was so disturbed that he actually talked to Dan Salvato himself (I forget the details of their conversation, but he had said that talking to Dan made him calm down, and that he was a really cool person!) Even as a 12-year-old, I watched clips of the game, since, as a story nerd, I was intrigued by how the game would break the fourth wall. Despite being intensely spooked, I don’t think I was even as genuinely scared back then. Of course, much of it might be the fact that this time, I was the one actually playing, and not someone watching from behind two layers of screens (as DDLC wittily breaks the fourth wall multiple times in the game, especially at the end.) However, I also felt that, even as a 20-year-old who is much more scared of horror than other people, with much more struggles with mental health than I did when I was 12, the themes of depression in particularly seemed to affect me more than I would have predicted, and I cannot imagine how they might affect someone, with mental health struggles, going in blind.

Figure 2: DDLC does have an extra warning on mental health, but I think there might be the risk of players disregarding or even underestimating the intensity of the content, since many other games and media have similar content warnings despite being much more mild in nature. There are also specific triggering moments that might not be expected / covered by this umbrella, general warning.

It seems that the age rating and content warning is the most drastically understated of any of the games I’ve playtested this quarter; I would argue that DDLC deserves a 18+ warning with a more explicit content warning than just not being “suitable for children under 13 or people who are easily disturbed”; for example, there is a certain, awful part where the player is forced to watch one of the characters stab themselves, then watch the body decompose over the weekend. I knew largely what was going to happen going in, and yet I still felt incredibly disturbed, and some parts and ideas even felt like they were somehow getting to my head (there’s a very disturbing ‘unlocked poem’ with implications of suicide and depression that was just dreadful.) However, I do understand that DDLC has to balance a milder content warning with the ‘shock factor’ that actually may be central to the game (and its standing as a feminist game.) Nevertheless, I am still startled at how much they downplayed it; I think it would be better to bump up the age rating to at least 17-18+ with a slightly stronger content warning (my cousin had also said that he suspected nothing when he came across the mild age/content warning.)

Figure 3: Agreeing to the terms and age rating

In Chapter 4, “Gaming Feminism,” of Shira Chess’s book Play Like a Feminist, Chess emphasizes the idea of agency in feminist theory as well as the role of redefining of familiar tropes in feminist games. In terms of playing with agency as well as redefining the conventional “dating sim” trope, DDLC succeeds at being a feminist game.

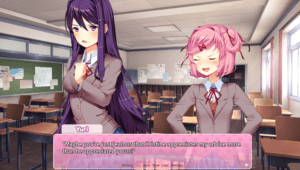

Firstly, and perhaps most apparently, DDLC begins with a subversion of the conventional Japanese visual novel dating simulator.

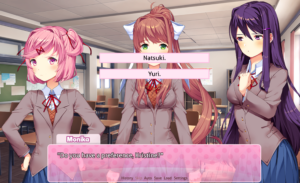

Figure 4: An opening full of cliches, potentially based on shounen romance anime tropes

The girls’ characters even fit perfectly into the dating sim stereotypes; there is Yuri, the shy and reserved girl, Natsuki, the “tsundere,” Sayori, the bubbly childhood friend, and Monika, the popular club president, and the nondescript male main character. Even the main menu seems to be a typical dating simulator design. The story is full of cliches: a club, a childhood best friend who has been in love with you leads you to join a club full of “incredibly cute girls.” The music is cute and girly, and so is the design. Despite just joining the club, the girls are also immediately competing for your attention, each of them jealous of each other.

Figure 5: Natsuki and Yuri competing for the male MC’s attention

There are also contrived scenarios; for example, there is a certain part at the beginning where Sayori and the main character go to get supplies, and Sayori drops something on her head. There is an awkward cutscene of her on the ground in a pose that seems to highlight her body. Another scene includes the main character buttoning up her blazer, and puts emphasis on her chest.

Figure 6: An unnecessary discussion on one of the character’s chests, typical of dating sims / media catering to the male gaze.

The sexualization seems to reach a peak when Yuri is in the MC’s home, and the MC cuts himself on her knife. The story text then describes Yuri licking the MC’s finger, then her acting shy and embarrassed about it. These scenes seemed to me like obvious sexualization, which made me particularly uncomfortable as a girl myself, playing.

Figure 7: Sexualization of Yuri

Chess briefly touches on the idea of male and female gazes. Although DDLC sets up the male gaze at first, in the case of DDLC, the game sets up the male gaze only to tear it down. The “fan service” moments quickly go out the door; one morning, after Sayori’s slow reveal of her mental illness, the player finds that Sayori has hung herself in her room. The game “ends,” and the player is taken back to a glitched main menu, where the sprite of Sayori is now replaced by a glitched Monika sprite. Things get progressively worse; instead of a “dating sim,” the game is revealed to be a psychological horror one. Upon restarting the game (I tried loading the game from Save, but it just said that Sayori.ch did not exist, and forcefully restarted the game), each time Sayori’s character appeared, there would be either a visual or text glitch, which was intensely unsettling. At certain points, the music also goes off-key, and there would be random, sudden jumpscare glitches in the game, deeply unsettling for the player who had just bought into the typical, slightly misogynistic dating sim.

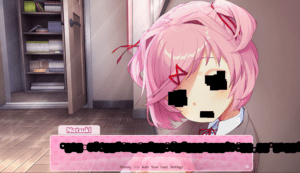

Figure 8: What started as a cute close-up scene with Natsuki transforms into a deeply unsettling glitch (after which there is a deeply unsettling scene with implications of Natsuki’s father abusing her. Blood leaks from her eyes, and her neck snaps, with “END” written, like after Sayori’s death, but spelled backwards, then things return to normal again, with no restart.)

Beyond simply breaking the genre, the game’s narrative also turns the stereotype of the dating sims on its heads in terms of characterization. The player realizes that the bubbly childhood friend has secretly been dealing with deep depression her entire life— Sayori even tells the main character that she knows this is something he doesn’t know, and somewhat scorns him for having her having to spell it out for him. The player makes fun of Sayori for being late to school, but Sayori reveals that her lateness is because most days, she cannot find a reason to get out of bed. Not only is Sayori’s character revealed to be more than a “one-dimensional” one, but Yuri, the shy and reserved archetype, turns out to have tendencies with self-harm and troubling obsessions. Natsuki implies (through a glitch I apparently accidentally unlocked) that her father abuses her, and often refers to DDLC as her “safe space.” Finally, Monika is not the perfect club president as she seems to be; she is the mastermind behind the events of DDLC, and is also plagued by self-awareness and the resulting loneliness.

After Sayori’s death, however; not only are there no longer any “fan service”-like moments, the game’s constant horror glitches and the escalation in tension between Yuri and Natsuki leads to a thoroughly unsettling atmosphere for the male main character. Thus, DDLC seems to play into the misogynistic stereotypical dating sim tropes only to break them.

Sayori’s death also ends with a monologue of the player questioning their decisions (ultimately, however, even if the player chooses to “friendzone” her, she still takes her own life) and there is a startling line in which the player says that “This isn’t some game[…]”— the consequences are lasting.

Figure 9: Breaking of the fourth wall after Sayori’s death, leaving player with guilt

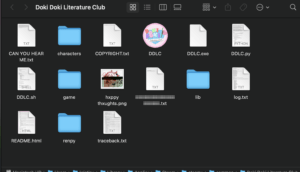

DDLC constantly breaks the fourth wall. For example, at one point, I checked my local files after Sayori’s death, and found creepy files:

Figure 10: Files after Sayori’s death on my laptop!

The breaking of the fourth wall uniquely forces the player to reflect on their own actions (as in Undertale.) The game doesn’t treat itself as a game. At the end of the day, it seems that all of this horror is happening to the player and the girls because of the structure of DDLC itself— an apparent dating simulator. After the player deletes Monika’s character file, Monika first lashes out at the player, but eventually brings back the game without Monika in it, thinking that this would be her final act of true love, since she was the “problem.” However, it turns out that without Monika, Sayori is the club president, and also gains self-awareness, remembering what Monika did to all of them. There are glitches of the classroom that Monika had trapped the player in, foreshadowing a potential ending where Sayori follows the same path as Monika did. The game thus criticizes its own structure in a meta way; Monika was not the issue. Even Monika is being used; she reveals in one of her text logs at the end of the game that when the player quits the game, it causes her excruciating pain and hears screaming, but she also can’t remember it. Ultimately, Monika intervenes, saying that she wouldn’t let Sayori hurt the player. She then apologizes to the player and deletes DDLC, saying that perhaps there was no happiness to be found in it. From a feminist perspective, it can be understood that the manipulation of the girls to be in a stereotypical dating simulator, as well as their pre-defined, one-dimensional characters, is the root of the evil.

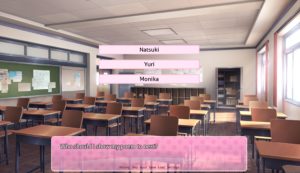

Additionally, as I played, I noticed how interesting the role of agency is in the game. From the very beginning, the player had no choice in their actions, even if they felt like they were deciding things, which was a meta way of the game taking the power out of the male main character’s hands into Monika’s. For example, no matter whose “route” the player goes for (presumably by writing poems that a certain girl would like), the events remain the same. Regardless of whether or not the player “friendzones” Sayori, she takes her own life. When the game restarts, the storyline also remains the same. Although I chose first to spend the weekend of the festival helping Sayori, then Monika, the game eventually forces the player to choose to spend the weekend with Yuri for various reasons (a task being too simple for two people to complete, for example.)

Figures 11-13: The illusion of choice over who to spend your weekend with— no matter who you “choose,” you ultimately are led by the game to choose Yuri. Looking back, the “Do you have a preference, Kristine?” becomes not only creepy, but mocking. The male MC is not controlling the game; Monika is. Even after the player deletes her character file, she is able to manipulate events as she disappears, and ultimately both brings back the game, and deletes the game. The male MC has no agency. Instead, Monika has all of the agency.

There are, however, well-grounded arguments challenging the authenticity of the feminism in DDLC, and at first glance, these arguments seem to validly challenge how feminist the game is. For example, the game places Monika into the role of the witch archetype, which does seem to be anti-feminist.

Figure 14: Monika at the end of the game, having deleted or corrupted the other girls’ character files, having trapped the male MC in the classroom with her, (presumably) for forever

However, Monika’s “evil” is revealed to be a result of DDLC itself, and not Monika in particular, as seen on Monika’s reboot in which she removes herself. Additionally, the game allows the player to gain some level of empathy for her, especially after she describes the sensations she feels when the player quits.

A more substantial argument is how the game might be seen as capitalizing off of the girls’ trauma. Yuri’s mental decline in general, although also heavily foreshadowed by her love of knives, is quite intense, and borders on being designed for shock value. Nevertheless, I think it can also be argued that this “shock value” contributes to the subversion of the genre, especially given that the game implies that the horrors that are happening to the girls is ultimately a result of the player as well as the game itself. Monika also seems to try to justify her own actions (and the game’s) by telling the player that these issues were already in the girls, and she was just “exacerbating” them. However, I was skeptical of how much of this trauma was necessary, and how much of it was intensified for the sake of the underlying genre (psychological horror)— especially given how triggering some of the content was. Overall, however, I think despite my initial impressions, the trauma does ultimately contribute to the subversion of the genre and its goal in criticizing and satirizing the dating sim genre and the “cute 2D girl” tropes.