Depression Quest is a 2013 interactive fiction game developed by Zoe Quinn, Patrick Lindsey, and Isaac Shankler initially for web browsers and later as a standalone game on Steam for PC, Mac, and Linux systems. A prologue for the web version of the game on its website clearly describes its target audience by explaining the game’s two goals: to give people without depression, but who want to understand it, a simulation of what it is like and to give people with depression a depiction of it that might help them feel less alone. While the narrative of Depression Quest isn’t explicitly feminist, it is fully consistent with the purpose of a feminist game as an “agentic training tool” as proposed by Shira Chess in her book Play Like a Feminist. Playing Depression Quest “like a feminist” can mean playing it with an eye towards its depictions of underrepresented backgrounds (particularly mental illness), power, and gender. Regardless of some minor critiques, which are themselves noted in the game’s prologue, Depression Quest fundamentally succeeds as Feminist media per Chess’ parameters.

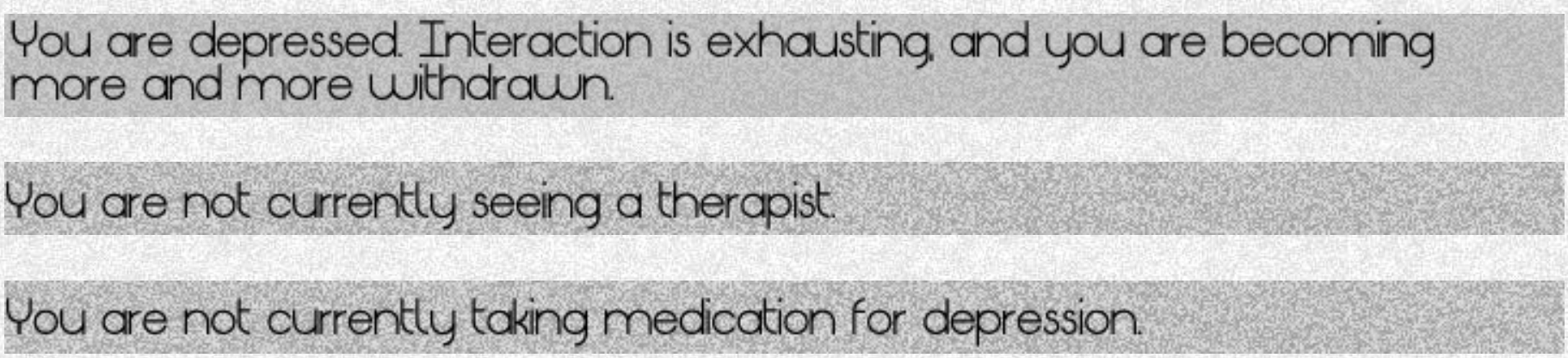

Depression Quest is an interactive fiction game, essentially a visual novel, that has the player take on the role of a depressed twenty-something as they grapple with worsening clinical depression. Following a multi-paragraph description describing a situation and the player character’s mental state, the player is prompted to click on one of multiple choices. The big twist on this style of storytelling is that one or more of the choices are unavailable based upon the severity of the character’s illness. For example, when faced with the choice of whether to attend a party with their girlfriend, the first option (implied to be the best given its prominence) is to “shake off your funk and go have a good time with your girlfriend”. Since this option has a line through it and is unclickable, the player can only “agree to go” or “say that you’re really just not feeling well and can’t make it”. This extremely simple mechanic of choosing an option from a multiple choice list, coupled with a persistent status indicator displaying the severity of the player character’s depression, their therapy status, and medication status, produces a dynamic of psychological exploration for the player. The player is free to make choices that will improve the character’s mental state, such as forcing them to attend social gatherings, adopt a kitten, and see a therapist. They are also just as free to decline every invitation, stay in bed all day, and sink deeper into the almost irresistible black hole of depression. Aesthetically, this accomplishes the game’s fundamental goals of depicting depression for education and comfort by having the player feel a miniscule, virtual fraction of the difficulty in navigating the illness. The game is an invitation to get inside a hypothetical depressed person’s head and see the intense difficulty of fighting their illness. In the best ending, even after taking medication, seeing a therapist, and making every best choice, the player character is still depressed, but much better armed against their condition, showing that the condition is something to be managed and cannot simply be willed away.

Fig 1: The player chooses whether to attend a party or not, with the best option of having a good time being unavailable. Status highlights show the state of the player character’s depression, therapy, and medication.

The game intertwines feminist theory as described by Shira Chess well and serves as a good example of a feminist video game as she describes it. Quoting Aubrey Anable, Shira Chess describes video games as affective systems that “can tell us quite a bit about the collective desires, fears, and rhythms of everyday life in our precarious, networked, and procedurally generated world.” Chess says “as we play things, we feel things, become things, and rethink things. There is nothing more feminist than this.” The game and the aesthetic responses it elicits follow these descriptions to a tee. It directly follows the “everyday life” of the player character while expounding on their desires (e.g. for success, for love, for contentedness), their fears (e.g. of failure, of breaking up, of getting worse), and their rhythms (such as their negative feedback loop of feeling depressed and frustrated, losing out on social opportunities and productivity due to those feelings, and having those feelings deepened as a result). For those without depression that are willing to have an experiential taste of it, they are made to “feel” these struggles, “become” the depressed character, and “rethink” what it means to have depression and deal with it. The game’s experience may not be an explicitly feminist one, as the player character’s gender is undefined and classical feminist struggles are not depicted, but Chess explains that this is not required for it to succeed as a feminist video game. She explains that “we need to tell stories not just about women but also about characters who face the adversities set forth within our mainstream cultures.” Depression is unfortunately an increasingly common part of modern life in the West and characters with depression remain underrepresented in popular media (can you think of a recent triple-A game where the protagonist is clinically depressed, or where the game truly grapples with that illness?). Depression Quest’s story therefore amplifies an under-depicted perspective and helps illicit feelings in the player that humanize a person with depression far beyond someone that is merely sad or a buzzkill. Because the game is an exercise in thinking and feeling in this way, it serves as an “agentic training tool” as Chess describes. The player gets a sense of what depression is like, what it means to fight it, and can depart from the game with more empathy for people with this condition while better able to support them and advocate for them.

Playing this game like a feminist means being open to the mental and emotional experience it seeks to create while also examining its depictions of underrepresented groups, power, and gender. As described above, the game is a valid agentic training tool to build empathy for those with depression, an underrepresented group. As such, its narrative is centered around power, even if it is subtle about it. While the game isn’t about combat or any explicit power dynamic, it primarily deals with the diminished agency of the depressed player character. We’re never told to what extent the character’s depression arises from an innate neurological condition versus a pathogenic environment, but their power is limited all the same. The game’s mechanic of removing options based on their mental state shows us things the player character would like to do, but is simply unable to based on their condition, revealing how depression directly restricts their ability to make good choices. Nonetheless, by still affording the player choices, the game becomes empowering. If the player consistently chooses the least bad option, forcing the player character to socialize, see a therapist, etc, their depression is slowly reduced until by the end of the game it has become manageable. This highlights that while the depressed character has much less agency than a neurotypical person, they still have some agency and, crucially, they have enough that seeking a fulfilling life is possible.

Fig 2: An example of the choices available when the player has been consistently taking more positive options (left) vs. more negative options (right). The more depressed they player character becomes, the more choices are unavailable (but still tantalizingly shown).

Fig 3: The epilogue screen. Rather than acknowledging a permanent state of victory like many games do, Depression Quest explains that depression is a never-ending battle, albeit one that can potentially be managed well.

When it comes to gender, the game doesn’t do much to explore this topic, but is suitably feminist. While the gender of the player character’s partner is specified as female, the player character’s gender is never stated, allowing the player to imagine it as they desire. Many games would lock in the player character’s gender in a story like this, but the developers apparently found that to be an unnecessary description and simply left it open. While some female characters, like the player character’s girlfriend Alex and friend Amanda are perhaps more stereotypically feminine, as they perform a lot of emotional labor in trying to help the player character, with Alex being particularly self-sacrificing, the player character’s mother subverts these tropes. The mother character is explicitly less understanding and emotionally available than their father or brother. She repeats unproductive advice to “work harder” and desire success more strongly, criticizing the protagonist for their directionlessness, while the father and brother try to restrain her. Just as in real life, the female characters in this game run from deeply emotionally intuitive like Amanda (who recognizes the protagonist’s depression and helps them get a therapist), to supportive and understanding like Alex, to complete obliviousness like the mother. Instead of gender defining the game’s characters, the characters are portrayed as realistic individuals.

Fig 4: The player character’s mother is significantly more critical of them than their father or brother, subverting common tropes about women being more emotionally aware and supportive than men.

The primary critique of Depression Quest is probably its lack of depth in its portrayal of depression and the relative ease with which it depicts managing the condition. To be clear, the game provides this critique of itself in its prologue, which states “Many of the following encounters deal with issues such as therapy, medication, handling a love life, and reaching out to support networks. In reality, less than half of depression sufferers actually seek treatment, for reasons such as lack of money, perceived personal failing, or public stigma. These things were included in order to touch upon as broad a range as possible […] though they will likely not be the experiences of most sufferers.” To provide an experience that can educate the audience about depression and its treatment options within an hour or two instead of it being super detailed and many tens of thousands of words longer, the game sacrifices some substance for accessibility. I recall reacting with some disbelief when the player character’s medication seemed to help them relatively quickly. It is only once mentioned later, in passing, that the player character had to try a few different medications before finding one that worked well. This gave me a pained chuckle. A close friend of mine, who has depression, took three years to find a good medication after their psychiatrists experimented with several different drugs and doses. That process was extremely painful, and to see it collapsed into the best case scenario within the game of a drug working fairly quickly (with the seeming only negative being a single scene of the player character having difficulty performing sexually) felt a tad unrealistic. But, again, the game provides this critique of itself and is meant to be a quick, accessible depiction of depression, so I don’t think it can be faulted too much. It provides a much deeper narrative than any other visual novel I’ve played and is much richer than any of the Choose Your Own Adventure series of multiple choice game books, which essentially have the same mechanics.

Fig 5: The prologue screen. The game begins by critiquing itself and acknowledging its inability to capture the full range of experiences had by people with depression

All in all, Depression Quest provides a thoughtful depiction of depression and is consistent with Shira Chess’ description of a feminist video game. The game skillfully depicts the struggles of an underrepresented character and serves as an “agentic training tool” for building empathy and advocacy. While not as detailed or realistic as it possibly could be, and not explicitly feminist, it is nonetheless a good example of an accessible experience concordant with feminist theory.