Pokemon Black, developed by Game Freak, is one of two Pokemon games released in 2010 for the Nintendo DS that takes place in the fictional Univa region, its counterpart game being Pokemon White. Made for Pokemon lovers, and especially children, Pokemon Black and White is a staple in the franchise.

Pokemon Black isn’t just a game filled with cute characters and combat, this game invites players to truly care about the world through an enacted narrative that allows players to immerse themselves into the world of Pokemon, mixed objectives, and strong but immersive boundaries.

Narrative:

Drawing inspiration from New York City, the Unova region marked a significant departure from previous Pokémon games by being set far away from the familiar Japanese-inspired regions of earlier installments. This geographical separation serves a narrative purpose—it creates a fresh slate where players can truly embody the role of a newcomer discovering an unfamiliar world.

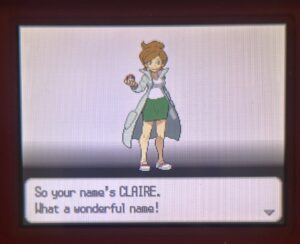

What makes Pokémon Black’s worldbuilding exceptional is how the narrative isn’t merely told to the player, it is enacted through gameplay. Unlike previous games, Black Version presents players with an entirely new Pokédex containing 156 brand new Pokémon. This design choice transforms the usual collection mechanic into a genuine journey of discovery. Each new Pokémon you encounter is a new experience, mirroring what a real trainer would feel exploring an unfamiliar region. The player doesn’t just read about Unova being different, but they experience that difference directly through gameplay.

Formal Elements:

Pokémon games have traditionally focused on a singular objective: become the Champion. While this goal remains in Pokémon Black, the game introduces a rich tapestry of mixed objectives that give players multiple ways to invest in the world.

The primary storyline involving Team Plasma presents a philosophical objective alongside the competitive one. Players aren’t just proving their strength; they’re defending a way of life and answering profound questions about the relationship between humans and Pokémon. This narrative objective gives emotional weight to the traditional gameplay loop of catching and battling.

The game further expands its objectives through side activities that each offer different ways to engage with the world:

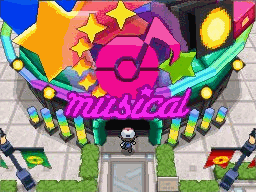

- The Pokémon Musical in Nimbasa City encourages players to view their Pokémon as performers rather than fighters

- The Battle Subway challenges players to adapt their strategies to different battle formats

- The seasonal changes introduce time-sensitive collection objectives

These mixed objectives prevent the world from feeling one-dimensional. As noted in “The Psychology of World-Building,” effective worldbuilding recognizes that “your story’s world is so much more than a beautiful backdrop.” By offering varied objectives, Pokémon Black creates multiple avenues for players to form meaningful connections with different aspects of Unova.

One of Pokémon Black’s most subtle yet effective design elements is its use of boundaries that feel organic rather than arbitrary. The game creates limitations that guide the player’s journey without breaking immersion.

Unova’s landscape features a stunning diversity of environments: sprawling metropolises like Castelia City alongside small towns like Nuvema, industrial complexes next to ancient ruins, and forests beside deserts. This environmental diversity creates natural boundaries. Rather than encountering invisible walls, players find their path blocked by bodies of water, tall ledges, or dense vegetation—all elements that make sense within the world’s logic.

The game also uses narrative justifications for boundaries. Early areas are blocked by construction work or trainers that require your Pokemon to be a certain strength to pass. These obstacles don’t feel like arbitrary game limitations because they’re integrated into the worldbuilding.

Ethics:

Pokémon Black boldly confronts ethical questions about colonialism and ownership that previous games in the series largely glossed over. Team Plasma’s core argument, that capturing and battling with Pokémon is exploitation, forces players to confront the colonial undertones that have always existed beneath the franchise’s cheerful surface.

The traditional Pokémon journey bears striking resemblance to colonial exploration: a young trainer ventures into “wild” territories, captures the native creatures, and uses them to gain power and status. Pokémon Black is the first game in the series to explicitly challenge this paradigm through its antagonists. When Team Plasma’s leader Ghetsis gives speeches about liberating Pokémon, he’s essentially framing trainers as colonial oppressors.

What makes this ethical exploration particularly effective is how the game doesn’t provide easy answers. While Team Plasma’s message appears noble on the surface, their methods are often violent and manipulative. Meanwhile, the game presents bonds between trainers and their Pokémon as potentially beneficial partnerships rather than simple ownership. The player’s Pokémon visibly grow stronger and evolve through their relationship with the trainer, suggesting mutual growth rather than exploitation.

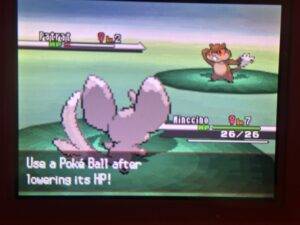

The game mechanics themselves contain this ethical tension. The act of capturing Pokémon involves weakening wild creatures and throwing balls at them until they submit. This is a process that, viewed critically, has troubling implications about power and consent. Yet these same mechanics allow players to build teams they care deeply about and form emotional connections with.

Overall, Pokemon Black is one of my favorite games in the Pokemon franchise, and is able to successfully immerse the players in the game through strong narrative design and formal elements.