A Dark Room is a text-based survival/adventure game developed by Michael Townsend, the lead developer of Doublespeak Games. While its ports to mobile devices (iOS and Android) and standalone PC reportedly add extra information and change some aspects of the game dramatically, the original in-browser javascript version of A Dark Room is already a masterpiece of minimalist worldbuilding. The player is fed a slow, but steady feed of narrative crumbs as they progress and uncover new mechanics and architectures, revealing a world that is literally much larger than when they first start. The pace of narrative development, exclusively text-based interface, and increasingly bleak tone may limit the game’s audience to older and more literate players (players who want a cheery or action-packed visual game will be out of luck), but what it loses in broad appeal it makes up for near-perfect execution of its unique wordlbuilding.

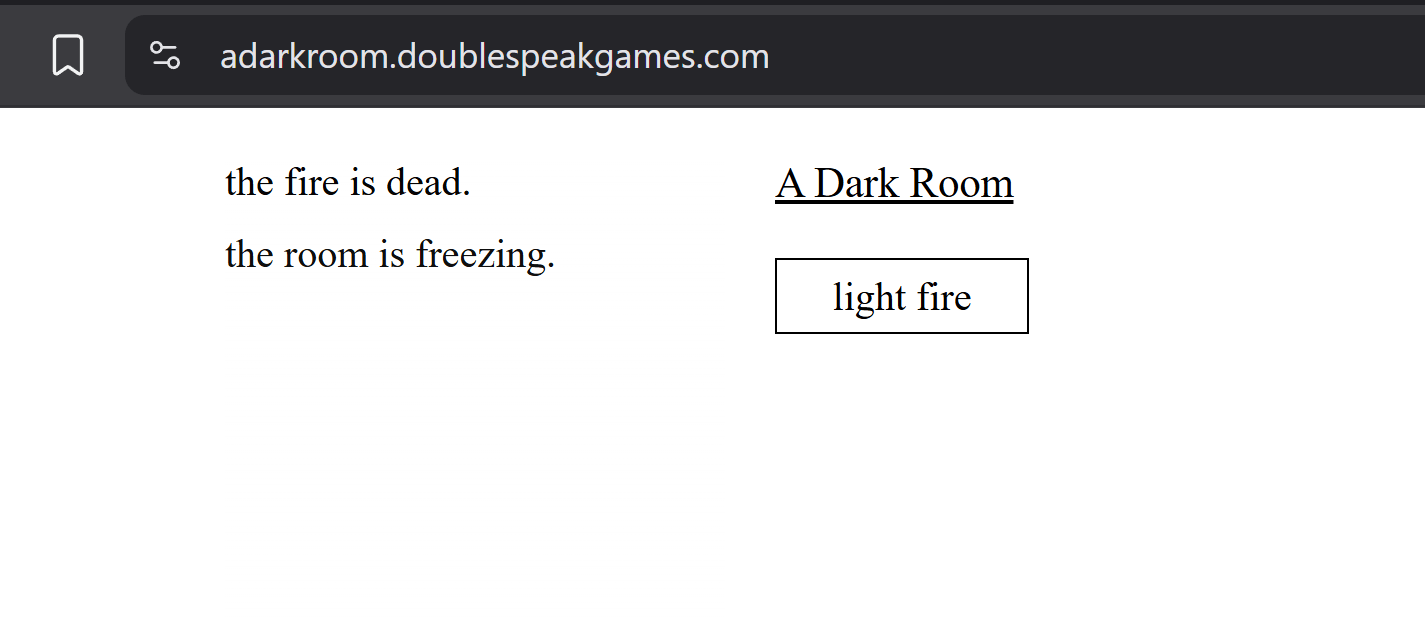

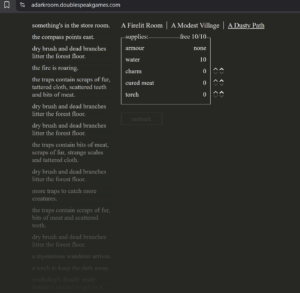

Fig 1: A dark room becomes a firelit room.

The game begins with extremely simple mechanics and dynamics, creating expectations of a more conventional text adventure and its usual worldbuilding methods. At first, the player only sees the title “A Dark Room” the text “the room is freezing. the fire is dead.” to the left side, and a singular button that says “stoke fire”. Pressing this button pushes the lefthand text downward and adds the text “the fire is burning. the light from the fire spills from the windows, out into the dark” and the title is changed to “A Firelit Room”. If the player enables sound, which appears to be a later addition to the browser game, they subsequently hear a looping sound of a roaring fire. A timer bar is overlaid on the button, disallowing the player from pressing it again until it completes. Stoking more frequently causes descriptions that the room is warm, or even hot, and that the fire is “burning” or “roaring”, while stoking it less often allows the room to grow cold again. This initial singular mechanic, gently timed button pressing, creates the dynamic expectation that the player must tend the fire in response to the descriptive text in order for more descriptions to be displayed, initially achieving a somewhat cozy aesthetic, especially in tandem with the sound of the fire.

This expectation is partially subverted when a “ragged stranger” stumbles into the room and collapses. Then the wind “howls outside” and the player is notified that “the wood is running out”, revealing the new title “A Silent Forest” alongside the firelit room. Clicking the forest title reveals a new button for gathering wood and a panel appears displaying the quantity of wood. Once again, the button press is timed, restricting how often the player can press it, and doing nothing for long enough results in the wood supply being depleted. With the addition of a single new button, this cozy text game has become a resource management game with the threat of perishing in the cold. Even if the task of maintaining sufficient wood stores is dynamically simple (just pressing two buttons occasionally), this task combines with the descriptions of the ragged stranger, howling wind, and silent forest to create a tense aesthetic experience. How long will we hold out against the elements? Will we eventually deplenish the surrounding woods and freeze? Will more strangers see our light in this dark, silent forest and harm us?

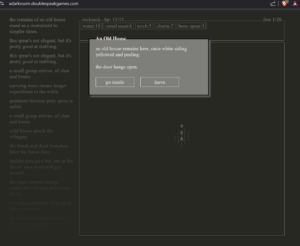

Fig 2: A silent forest becomes a tiny village (and I realized the game has a dark mode).

Eventually, the stranger recuperates and reveals she “builds things”. She can make traps for “any creatures that might still be alive out there” and that there are “more wanderers” who would be willing to work if we build huts for them, expanding the game space’s architecture with text instead of graphics. They say a picture is worth a thousand words, but the game’s brief descriptions like these might be too in the depth of their implications: the player must survive following some disaster that has wrecked the surrounding environment so thoroughly that most surrounding animals are dead and that people have been left without homes, and without a functioning government to relieve them. With this, a crafting menu is introduced in the firelit room, allowing the player to build huts that are eventually settled by more strangers, who can be designated tasks in the space outside the room, which transitions from being called “A Silent Forest” to “A Lonely Hut”, to “A Small Village”, and eventually “A Raucous Village” with up to 80 people. The game has simply added on more buttons to press and more resources to manage, but these simple additions make the game much deeper dynamically, as the player keeps track of how much wood they should have villagers gather to build a hunting lodge so some other villagers can be assigned as hunters and then charcutiers to smoke meat for long-term storage, which requires burning wood, etc. When the builder character says she can make traps for whatever is “still alive out there” and that there are “more wanderers”, presumably these strangers that become our villagers, it evokes an aesthetic of desperation that works well with our growing village. We are fighting to rebuild the world after some sort of collapse. Strangely, many resources we produce, like cured meat, appear to serve no purpose and simply accumulate. It almost implies that the player character is preparing for a long journey…

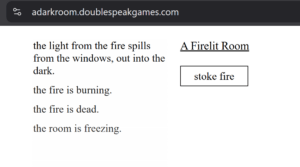

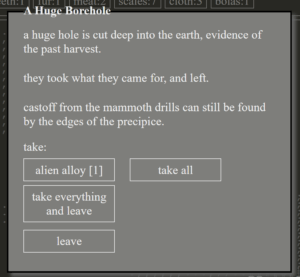

Fig 3: A disturbing east-pointing compass reveals a dusty path.

After some time, the game takes a huge mechanical step change that quite literally reveals the rest of the game’s world. If the player saves up the resources necessary to build a trading post, they are able to purchase a compass in exchange for fur (and some other resources). If they do so, a new tab appears titled “A Dusty Path”. The only accompanying description is “the compass points east”, which may sound innocuous, simply guiding us towards something to the east, but there’s a devastating implication: something has overwhelmed the Earth’s natural magnetic field. Compasses are supposed to point north, after all! Something is seriously wrong, perhaps wrong with the whole world. Clicking on the new tab reveals a panel for assigning resources to an expedition and allows the player to embark, revealing a text-based world map similar to the 1980 dungeon crawler Rogue. The previous game world consisting of the cozy firelit room and, by now, a large or “raucous” village has grown to feature an actual navigable overworld.

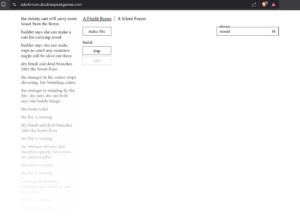

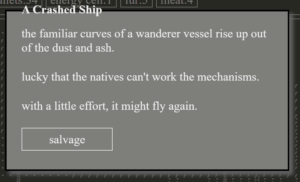

Fig 4: The player comes across an “old house” in the overworld, immediately prior to entering and slaying its inhabitant.

The player requires cured meat, a previously useless item, to move two spaces, implying that these map cells are quite vast since uncured meat isn’t sufficient to traverse them since it would spoil. And just as our horrifying compass implied, the world consists of wastelands, dead trees, rotting structures, and tons of creatures and people who attack us on sight. From our first encounter in an old house with “yellowed and peeling” siding, where its occupant immediately attacks us, we don’t meet anyone that doesn’t want us dead. Wandering farther results in encounters with soldiers and snipers that shoot us without any warning. The initial implication is simply the desperation of a dying world, but it is a little odd that nobody even offers to trade, or even shouts a warning at us. If the player finds or crafts weapons, they can press buttons to use them during combat encounters and deplete enemy health, but strangely they can simultaneously equip and use a spear, iron sword, steel sword, and rifle. This almost seems to imply that the player character has multiple arms, but that would be ridiculous. Lots of games let the player carry and switch between weapons with unrealistic alacrity. It’s the same here, right? …Right?

Fig 5: Descriptions revealing the world’s conflict with apathetic alien invaders who “took what they came for, and left”, and that we’re one of them.

Eventually the player may find former battlefields with normal industrial era weapons, but occasionally “energy cells” and “laser rifles”. And then they find “giant boreholes” that are evidence of “the past harvest”. Whoever it was “took what they wanted and left”, but there are still bits of “alien alloy” left behind. We never see another human character operating a laser rifle, but we are able to while simultaneously swinging a sword and thrusting with a bayonet. This is why soldiers and everyone else, even emaciated nomads, attack us on sight, isn’t it? This whole time, as we’ve been invading abandoned buildings and annihilating their starving occupants, we’ve been a literal space invader, albeit one left behind by their fellows. This is confirmed when, in the east where our compass has been pointing, we come across a “crashed ship”, described as a “wanderer vessel”. Its description also says it’s “lucky that the natives can’t work the mechanisms”. Upon salvaging the ship, we see the player character’s reflection that they’ve “been on this rock too long”. The whole world and all of its people are just an annoying rock.

And there we have it. The game starts as a minimalist text experience, grows to become a survival game and resource manager, village builder, and exploration game before culminating in a brief agility section as we navigate our ship through a debris field and escape the devastated Earth. The worldbuilding grows as the mechanics accumulate and dynamics become more frenetic and interactive, with the player reading more and more brief descriptions, each dripping with horrific implications. The aesthetics move from a player experience of somewhat cozy resource management to nerve-wracking exploration and combat, and finally to aloofness. By the time the character has enough resources and weapons to reach the crashed spaceship and leave, they are strong enough to explore the world with impunity, effortlessly laying waste to any “natives” they come across. Despite the fire we tended and the village we built, what initially seemed like a bright hope in a dark world, we just… leave. Like it all meant nothing to us. We didn’t build huts to shelter people, but to attract desperate workers to gather food, to mine coal and iron and sulphur for us. When we build a steelworks, “a haze falls over the village”, but we don’t care. Plagues sometimes roll through our village, sometimes killing almost everyone, but they are replaced by more desperate nomads almost immediately. Why should we care about using these tiny people up?

Fig 6: With now simple and non-congratulatory this victory screen is, it seems the player character looks back on their experiences as merely a fleeting obstacle unworthy of consideration. Like all of the resources we hoarded and pillaged, and all the villagers we used up, our entire experience can just as well be described as a number.

The carefully crafted descriptions of in-game events build the game’s world and, in retrospect, recontextualize the game’s central mechanics of buttons and resource counts: this is how our invader literally perceives the world around them. They don’t see human beings or animals, but resources and obstacles. Go mine sulphur. Make that creature into food. Stop being alive and give me your backpack. Oh, it’s empty? Whatever. Keep moving. And so on. A secondary playthrough even reveals a “destroyed village” with remnants of the resources we previously accumulated, showing that the village was only maintained to support the invader’s goals and was simply left to collapse behind them. Just like the other invaders who left us behind, all we ever do is take what we want and leave.

Ethics – In the game you played, how do the mechanics depict the body?

As discussed above, the player character of A Dark Room is mechanically able to use several weapons simultaneously during combat encounters. While many games sacrifice realism for fun and have absurd implications if seriously considered, A Dark Room actually intends these implications. Why is the adventurer of our adventure game seemingly attacked on sight by every animal, person, or group they encounter? Well, as the simultaneous use of spears, swords, and rifles implies, we don’t have a human body. Our alien “wanderer” body seems to literally have more than two arms as the mechanics imply. The usual power fantasy that many games featuring combat employ is somewhat inverted here. The player character, once they have the resources to do so, can easily annihilate anyone they come across, spamming devastating attacks with their many limbs. In this text-based game, the player is never explicitly described, meaning that their body can exclusively be described mechanically. We’d have to be some sort of vile, many-armed monster to attack with so many weapons so quickly and to inspire immediate combat encounters with everyone in the entire game world if its implications were followed through. And they are. This biological otherness from everyone else in the world seems directly to the player character’s implied apathy towards its inhabitants and ultimate abandonment of the village they built, which solely served as a means of resource acquisition. Our character is much more capable than any other being in its surroundings and accordingly affords them no humanity. With our superior alien body, everyone else is an expendable tool to be used up or a fleeting nuisance to be erased.