For this week’s critical play, I playtested Homebody, a puzzle game with a horror twist, available on platforms such as Steam and Nintendo Switch, made by Game Grumps and released in 2023. I playtested on Ellie’s Switch for about two hours, and although I generally got a sense of how the puzzles in the game worked, I unfortunately was not able to complete the game. While there seems to be no specific age rating, I did find on the European version of the Nintendo website an age rating of 16+ by PEGI, which is apparently a European video-game-rating system. I think the age rating might be fairly accurate (I think a brave sixteen year old could handle this level of horror, but maybe not me.) As mentioned in my previous playtests (I seem to be consistently playtesting creepier games), I am a bit anti-horror, and this game was definitely out of my comfort zone in terms of scariness. Ellie first pitched the game to me as a game that is designed to be horror, but most people don’t consider it to be.) When I searched up the ending, I think I agreed with them a bit more, since I do think the ending alleviated the horror a bit. While experiencing the time loop murders— I didn’t know there was going to be an element of survival when I blindly went into the game!— and not knowing what was happening, however, it was terrifying. However, even beyond the horror and repeated death elements, I do think that because of its more serious topics, the game might be more suited, even, for an older audience (perhaps 18+), or at least an older audience might be able to fully appreciate its themes of agoraphobia, aging generally, and drifting friendships.

The puzzles of Homebody, unlike Cube Escape: Paradox, perhaps, don’t necessarily slowly reveal or hint towards the central narrative, but instead play a role in uncovering and developing the overall atmosphere of the game, through developing the architecture, as well as uncovering a sort of parallel narrative / subplot. Additionally, especially near the beginning, when the player entirely lacks information, the key to solving some of the puzzles is interacting with the friends of Emily, the main character the player plays as. (This is, however, based on the two hours of my playtesting, since I wasn’t able to play the entire game, supplemented by a 2x speed watch on a four-hour playthrough.)

For example, interacting with one of Emily’s friends after discovering the computer upstairs leads to them saying that the player should talk to Megan, one of Emily’s gamer friends, if they are having trouble with the computer upstairs. Megan is then able to explain the computer game, which is Minesweeper. After successfully winning Minesweeper, I was able to use the winning pattern to unlock a box in the cellar, which allowed me to turn on the power (although this was right before I was killed again, and we were kicked out of CoDa early.) Thus, the puzzles themselves (like the Minesweeper minigame) don’t necessarily add to the narrative, but do urge the player to interact with Emily’s friends for more information— who do reveal bits of the past, and narrative. For example, there are hints of resentment from Cliff about Emily feeling “above them” (which actually, after wacthing the full playthrough, might just be something he concluded from her self-isolation) and throughout the game, hints of not having seen each other in a long time. There are also references to past events in some of dialogues (which are fleshed out in flashbacks between deaths.) Dialogues also ultimately reveal that the friends are unaware of the time loops, and that Emily cannot talk about anything related to the time loop; if the player selects an option about death or the time loop, the dialogue rewrites itself (a thoroughly unsettling element that horrified me.)

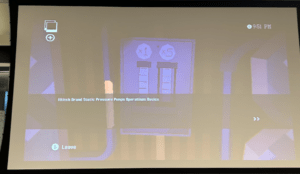

Like in the previous games I playtested, this game also had the mechanic of walking and looking more closely at objects as a puzzle game, lending itself to the dynamic of exploration, which overall allowed for uncovering of puzzles and architecture. One of the puzzles that I solved, for example, was through looking through a few drawers in a room that I assumed was a library or study. If I remember correctly, there were twelve of them, but most of them were irrelevant, or unsettling (for example, there were small skulls in one of them, and dead bees in another.) In one of them, however, I found a page number ripped from a book. There were several other books around the house, including Frankenstein and Dracula, which seems to set the tone of the game, as well. I eventually found the matching book downstairs in the living room, which was apparently also an unsettling book (I had not personally read / didn’t recognize it.) Upon reaching the page that had been ripped out, the page had been replaced with a piece of paper with Roman numerals with colored rectangles behind them (and although I didn’t reach the part where I was able to use this information, the full playthrough eventually reached a place where this code was required to unlock a new area.)

Figure 1: New page with pattern / clue necessary to unlock a new area later on

As such, although the book itself did not necessarily add to the plot, the exploration of other monster-related, sci-fi, Gothic horror books as well as general exploration of the house (discovering skulls or dead bees) contribute to the eerie atmosphere. From the sped-up playthrough, eventually it seems that you tinker with a sci-fi machine in the attic, which epitomizes the idea of new worlds requiring new architecture, but in hindsight, also seems to be foreshadowed by the book choices (especially Frankenstein), a touch of subtlety / vague allusion that I appreciate.

On the other hand, many of the puzzles do contribute to the parallel subplot, with Nest, the original owner of the real-life “house.” While exploring the house in an attempt to solve the puzzles, the player is able to interact with several notes, sticky notes, letters, manuscripts, and other documents, which reveal the subplot of Nest, presumably a writer, and a mysterious ‘C,’ who Nest is probably friends with (the playthrough reveals that ‘C’ is a character named Clara, who apparently was close to Nest, drifted away from him, but then reconnected with him eventually, much like Emily’s narrative (or, hopefully, her eventual narrative, as the ending foreshadows.)) As a result, it is not necessarily the puzzles themselves that reveal the narrative or contribute to the tone, but the mechanics of there being puzzles and there being walking that lend themselves to exploration and attention to detail that build the game’s atmosphere and subplot.

Additionally, many of the puzzles (at least the ones I played in the two hours) reset after death. Although you now know how to solve them, and are able to recall the patterns from clips stored in your Memory Log, on each time loop, you have to run around the house, re-completing puzzles.

Figure 2: The Memory Log, earlier on in the game. Accessible at any time by pressing ‘+’

The mechanic of completing the puzzles in a certain amount of time truly added the dynamic of stress to the game. Each time the time loop resets, Emily is sent back to 7 P.M., and depending on what room Emily is in, the Killer comes at around 10-11 PM (note: time passes differently/quicker in the game.) As a result, you only have three hours in the game to re-explore or re-complete various tasks. There also is no way to fully escape the Killer; on one loop, I hid in a closet until around 3 A.M., at which point I was somehow stabbed within the closet. The time limit on the puzzles themselves, then, also effectively add to the horror. Even when the Killer is not yet present, the pressure of completing the puzzles, constantly watching the time, makes the player feel like they’re constantly watched or escaping from something, an idea present throughout the game. The constant reset of the puzzles, however, seemed frustrating. I wonder if the reset of the puzzles truly contributed something to the game, or if it was to better complement the idea of time loops; in terms of mechanics, however, I think it might be more of a design flaw. One can imagine how frustrating it can be, especially later in the game, to keep dying because of a single error or not running fast enough from the Killer, and having to constantly redo the same puzzles despite knowing the answers (knowing the answers defeats the puzzle’s purpose, and instead turns it into a fiddly game of survival.) I did appreciate the Memory Log, however, since I think it would be far too much to try to remember everything, or even remember to take pictures of everything potentially relevant (time also pauses while in the Memory Log.)

Many of the puzzles also perhaps reflect psychological elements (an idea that I see in hindsight, that the ending supports)— for example, most of it seems to be unlocking things, such as doors, contributing to the idea that Emily is trapped in her “house” (or is a “homebody”); at many times, the characters also bring up the question of the strange homeowner and whether the quirks of the house are designed to protect him or others (a nod towards agoraphobia), and there are also constant elements of danger, even beyond trying to escape the Killer; for example, in the playthrough, there is electrified water, hot gas that can kill the player, etc. (the hot gas, at least, was foreshadowed during my playthrough when I encountered a brochure on burns and an interesting T/F section, one of which included the dangers of hot gas. I may have been playing way too thoroughly and not focused enough on running from the Killer.)

Thus, although the puzzles themselves may not necessarily contribute to the narrative or structure of the game, they do certainly allow the game to progress, and also lends to exploration and interaction that does reveal narrative. And, in a meta way, the existence of these puzzles also forces Emily to interact with the friends she has shut out of her life, in order to piece together the strange situation that they’re in.

Interestingly, I did realize that many puzzles in the game did rely on outside knowledge, but the game combats the lack of knowledge well. For example, the computer game was Minesweeper, a game I didn’t even recognize. I personally have not played Minesweeper before (and was lucky that someone at Game Night explained it for me), but for players like me, Megan is available as a resource. As I mentioned before, through a chain of interactions with Emily’s friends, I also interacted with Megan, the ‘gamer friend,’ who both identified and explained the rules of Minesweeper to me through a dialogue. Thus, even if I didn’t have someone in the room who had experience with Minesweeper, I would still be able to play the game, an information-accessibility feature I appreciated greatly.

There are, perhaps, also more hidden references (for example, with the books— the one with the page torn out of it was one I didn’t recognize, but that one of the characters mentioned as a creepy book), which might be appreciated more by someone who is familiar with these novels (I did appreciate, for example, Frankenstein and Dracula being books available.) However, the books themselves are not at all necessary for the gameplay.

There also were many confusing puzzles having to do with air or water pressure, as well as puzzles with gas and electricity, but conveniently, one of the friends (Cliff) is experienced in electricity, and another (Gary) knows a thing or two about gas, and when the player might need information regarding these topics, the player can interact with these friends for more information. In this way, Homebody does a wonderful job with including those who might not have experience with information not generally or widely known.

Figures 3/4: Just two of the many pressure and locking/power mechanic puzzles in the game

Extra: so true, Pete. Thanks!

Yes, very hard. Very scary, too.

Pete, my thoughts exactly. Especially after going in blind and not knowing that I was going to even need to worry about being murdered in what I thought was a eerie, conventional puzzle game : (