For this week’s critical play, I playtested Cube Escape: Paradox. I played Chapter 1 of the game on Steam. The game was released on Steam in 2018 and was made by Rusty Lake as the tenth game in the Cube Escape series. According to the Apple App Store— since Cube Escape: Paradox is also apparently offered on iPad— the game is for a target audience of ages 12+. I would argue, however, that it might be better suited for people 16+, as some of the scenes were darker and a bit disturbing; the player is playing as a detective who has amnesia, but is uncovering a potential murder while restoring his memories. The game involves blood and implied violence (a beheaded deer at one point), and has a few jumpscares. Although there is no inherent harm in a twelve-year-old playing this game (there’s no gore, graphic violence, etc.), as someone who didn’t stomach horror very well at all (and still barely can), I undoubtedly would have felt uncomfortable and scared if I played this at twelve. The game might be better intended for a slightly older audience with an appreciation for mystery, escape rooms, and a bit of psychological thrill, and so the game might benefit from a slightly higher age rating.

Figure 1: Sudden eye in keyhole accompanied by sudden sound and flashing white, which scared me

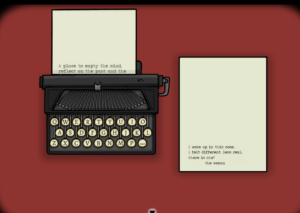

The highly fragmented narrative of Cube Escape: Paradox is created as a mystery through its mechanics. The game has the limited mechanics of moving between three rooms, limited zooming in and out of objects, collecting objects, and using objects. Although the game is unlike a walking simulator in that there is no mechanic of explicit walking, the mechanics of Cube Escape: Paradox, which allow players to move around the space and examine new objects, as well as old objects in a new way, nevertheless lend themselves to the dynamic of exploration, which allows players to slowly uncover an embedded narrative. Perhaps most importantly and obviously, the puzzle, minigame-like mechanics that underlie the game lead to the uncovering of this mysterious narrative. For example, assembling the fragments of a torn picture leads you to type a phrase in the typewriter, which leads you to the next clue, and so on. Entering the correct pattern into a lock might reveal a key, which unlocks a globe and releases flies that you have to match to objects in the room, before unlocking a puzzle in your— the detective’s— own brain. The game is set up like a digital escape room, where one available clue leads you to the next. In this way, the narrative slowly reveals itself to the player.

Figure 2, 3: Picture in early stages, which, when assembled, flipped to the back with the phrase “the woman” and a typewriter icon.

Cleverly, the game gives clues that the woman has been murdered before the game even begins. For example, the first scene shows the player opening their eyes, and in one blink, the woman appears, then disappears. There was also a reference to her in the monologue (something along the lines of “Who was she?”) The game confirms her death at a certain point, but, although some things are non-linear (for example, I snipped off a twig off of a plant way before it was meant to be used), the game also controls how much to reveal. It is impossible for some puzzles to be solved and some clues to be obtained before others (the key to the box holding the next key, for example, has to be obtained before the second key.) For example, in the series of pictures that the player has to color in with the pencil item, the last one asks the player to fill in a line across the woman’s throat, which begins to bleed, and she sinks into the picture of the lake. This is not definitive evidence, given that the entire game is a bit hallucinatory, but later on, a puzzle rearranging a shelf of books reveals a book of evidence that asks for a picture of the body, a scrap of a newspaper article with a headline debating whether the death was suicide or murder. In this way, through its mechanic of giving players bits of revealed information after puzzles are solved, the game slowly hints towards, then reveals, that the woman has most likely been murdered.

Figure 4: The woman in the keyhole

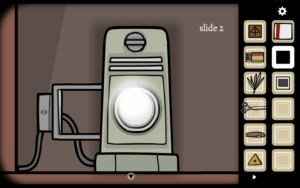

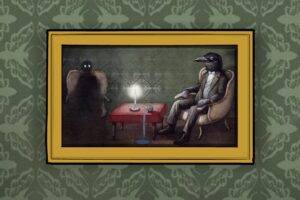

The architecture of Cube Escape: Paradox also controls the story. As the article “The Role of Architecture in Video Games” argues, the architecture of Cube Escape: Paradox is like the set of a movie; indeed, there are only three rooms that the narrative and mystery takes place in. Much like sets, many objects and furniture are also repurposed; for example, the TV, tape recorder, and projector are used to show multiple clues with different channels, tapes, and slides. The box on the bottom shelf also takes in multiple combinations to unlock different objects. The architecture contributes to the dynamics of concealment and exploration; as you move through the three rooms, zooming in and out (mechanics), the architecture and objects are the things being explored, and often hidden. Although I did appreciate the resourcefulness, after a while, the objects did seem to lose their mystery, and began to feel a bit mundane. Although perhaps the game wanted to limit itself to the three rooms and minimal objects in each, I think it might be nice to be able to either spread the repurposing across objects (there was, for example, a lot of reuse of the TV, whereas the phone, for example, was only used once), or add a few more objects to be explored.

Figure 5: Reuse of projector, with “slide 2”

In terms of secondary functions, however, Cube Escape: Paradox accomplishes many of these well through its architecture. For example, the hotel room–like, lodge-in-the-woods-like architecture certainly contributes to the atmosphere of the game. The wallpaper is slightly faded, which gives it a slightly unsettling quality, and the contrast between the flyer of Rusty Lake being a place for mental health rehabilitation and the detective switching from suffering amnesia to having mental breakdowns is also eerie. The sudden changes in architecture— for example, the sudden jump scare of the eye appearing in the keyhole, or the mirror frosting suddenly while the player’s reflection is replaced by the dark ghost— also contributes to the darker atmosphere. The idea of a “new world requiring new architecture” also seems to show its head in the game; for example, several characters are introduced throughout the architecture— whether it be through the books on the shelf, the files in the drawers, the videos on the TV, or the painting in the room. Cube Escape: Paradox builds its world in this way, with motifs of the raven head, the dark ghost, the woman, and the beheaded deer.

Figure 6, 7: Room with projected photo of detective and woman as a clue, with the painting of the dark ghost and raven head underneath (default, without the projector)

Lastly, Cube Escape: Paradox takes advantage of familiarity, particularly with the mirror in the room. Upon first exploration of the three rooms, I was drawn to the mirror first, because I wanted to see what I looked like, or if the game would shatter the familiarity. The game made sure to let the player know that the reflection in the mirror is true, however, since, when I clicked the cigar and coat in the mirror, the detective man in the mirror held the cigar and put on the coat. The player resultantly is able to confirm their appearance and identity.

Figure 8: Reflection in the mirror, when I started the game

Figure 9: Reflection in the mirror, when I put on the coat (guided by the man in the mirror saying “I’m cold”) and held the cigar

Although I only played the first chapter, I did have qualms with the overall narrative. The detective questioning his own identity and the evil shadow appearing in the mirror’s reflection led me to think that the detective (the player) himself killed Laura, or “the woman.” After playing, however, a search on Google revealed that the many games in the series come together to form a massive, complex, and confusing story based on pure theorization from players themselves, where Laura probably killed herself, and the Paradox game in the series was just a “test” by the raven head figure for the detective. I do not know if Rusty Lake wanted this effect, but I do think that if they wanted the narrative to be clearer, they certainly had the mechanics to reveal a complex narrative. Perhaps the narrative itself was not clearly thought out, or they had to abandon or extend it at a certain point, or they intentionally left it as one, large, meta puzzle outside of the games for players to piece together. As it is, though, the narrative is too open-ended to feel fulfilling.

Sadly, the game was not very accessible. Although there were captions when the players were talking, which might aid deaf players, there were no other accessibility features.

Figure 10: Limited game settings

Additionally, the audio (with accompanying captions) and fast-paced videos were not pausable, which makes it even more difficult for those who might be hard of hearing or have vision impairments. Someone also mentioned last week in section that one potential accessibility feature for escape rooms and puzzles to address learning disabilities is the providing of hints. Not only did Cube Escape: Paradox not have hints, but at one point, there was a bug in the game (after I unlocked the globe key) where I could not retrieve the object. I Googled the bug, but it seems like people from 2018 were also encountering it, and people said that it was unfixable, unless they reset the game entirely. Being halfway through (already having played 1.5 hours), I was deeply frustrated.

Figure 11, 12: Literally inaccessible globe key— resetting graphics did not work : (

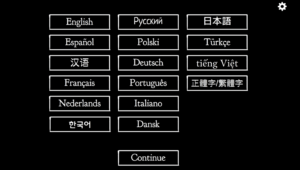

Additionally, I was stuck on the phone dialing for a long time. Not only did I not know how a rotary phone worked (and had to ultimately search up how to dial it), there was no feedback when a number was pressed before rotating. I think the game would benefit from more accessibility features, as well as perhaps more feedback in some areas (such as with the phone, or one particular box where the symbols slide up and down to change rather than by tapping.) I did notice, however, that the game is offered in multiple languages, which does make the game accessible internationally, which I appreciated.

Figure 13: Language options!