Print & play

Design Mockups

Final Playtest YouTube Link

Artist Statement:

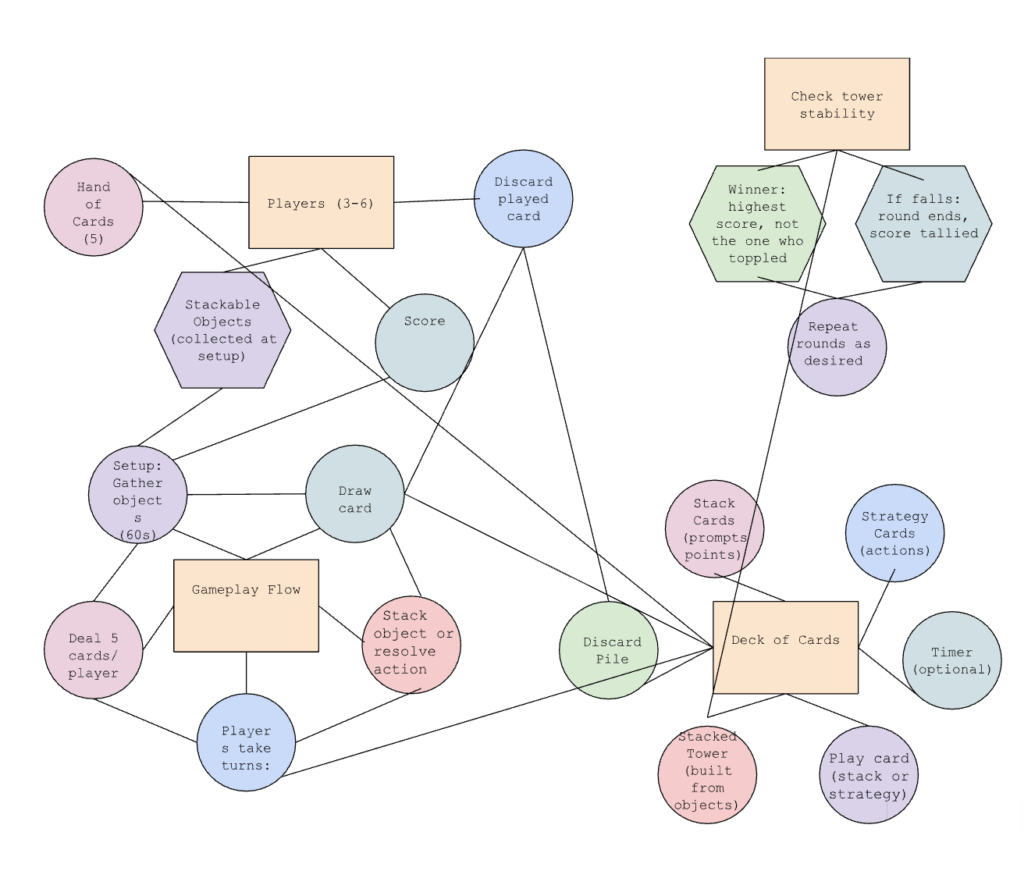

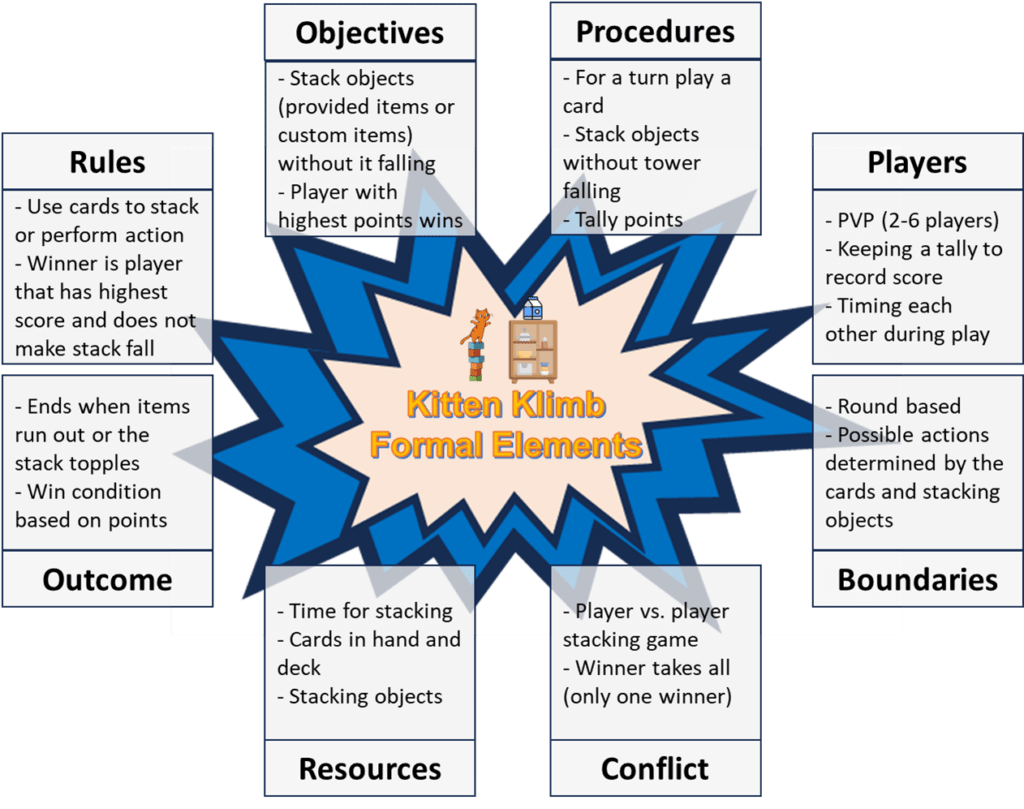

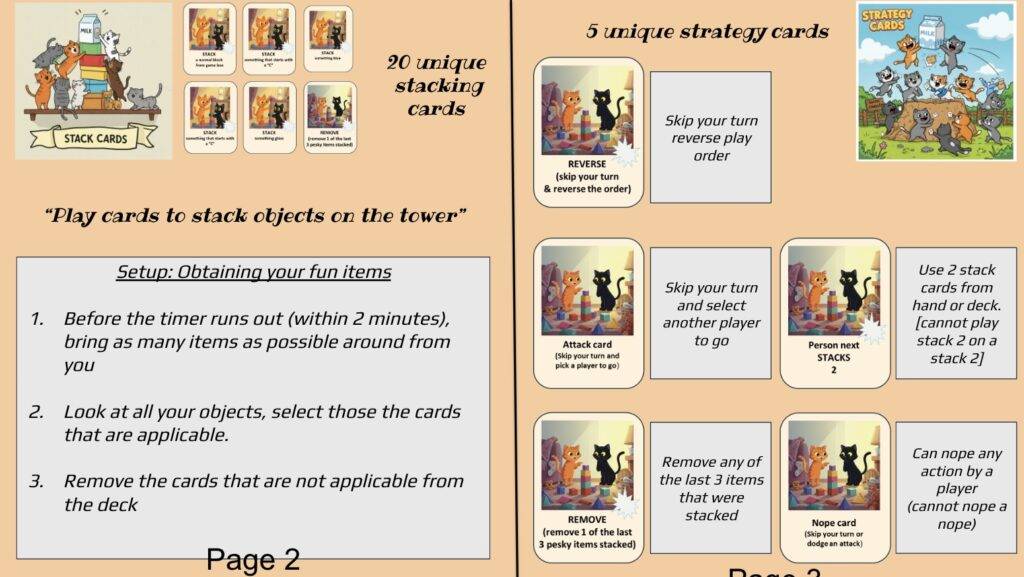

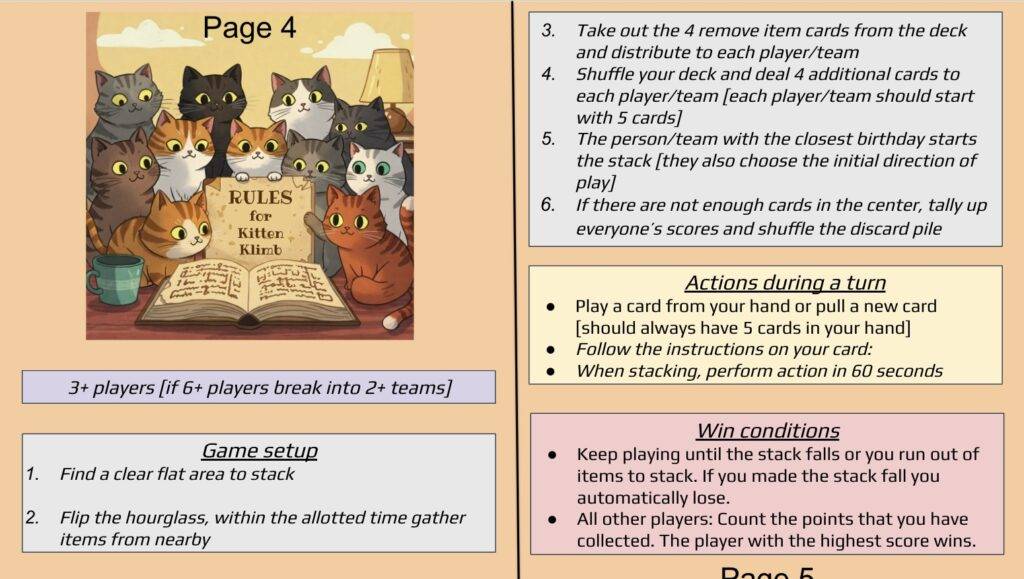

Kitten Klimb is a tower-building card game meant for 3 to 6 players. We wanted to design a light-hearted party game appealing to all ages that leverages items in the players’ surroundings, rather than only using a predetermined set of items in the game box. At the start of each game, all players have 60 seconds to grab any potentially stackable objects they can get their hands on and bring them to the play area, setting a chaotic and silly tone for the round to follow. They then each receive a hand of five cards. This includes stack cards with point values that specify a characteristic of an item to stack (such as its material, texture, use, etc.) and strategy cards (such as skipping a turn, choosing a different player to take a turn, etc.). This adds an enormous amount of choice to each player and facilitates friendly competition. It might be easier to skip your turn, but you only gain points by stacking! Whoever has the most points when the tower falls wins (as long as they didn’t knock it over)! We believe we have succeeded at creating a game rich in physicality, achievement, and (friendly) competition.

Target Audience:

When designing Kitten Klimb, we aimed to create a game that is accessible to a wide audience—that is, a game that allows players of different age groups to play together. We drew inspiration from popular party games like Jenga (ages 6+) and Exploding Kittens (ages 7+) and combined the best elements of each game’s mechanics to form the foundation of Kitten Klimb. This includes physical block stacking, as well as stacking cards and strategy cards that guide the flow of the game. For our game, we settled on a design age of 7+, as the complexity of the mechanics is as elaborate as the ones in Exploding Kittens (i.e., the players will need to be able to read and understand the contents on the card).`

Based on feedback from playtesting, we revised the rulebook to make it more easily understood by a broader audience. During our most recent playtest (we had three playtests), conducted on April 22, 2025 (see the associated playtest video), players expressed some confusion about the game’s rules. This was largely due to the rulebook being overly lengthy and wordy (see quotes below and associated changes).

Player 1: “I am a bit confused by the rules of the game in the beginning because there are a lot of words…”

Response to Player 1: To address this concern, we shortened the rulebook and simplified the language to make the rules easier to understand. Additionally, we reduced the amount of text on each page to improve readability and maintain engagement across players of all backgrounds.

Player 2: “I think the game could benefit from pictures in the rule book”

Response to Player 2: To address this concern, we modified and added some pictures into the rulebook to help improve the learning experience of the game, especially for new players (accounted for this in the content, and also the order of the pages in the rulebook).

Player 3: “When can one card be played- especially after an attack card”

Response to Player 3: This concern was related to the use of the “Person next plays 2 STACK cards”, where some players were confused about whether they could keep playing “Person next plays 2 STACK cards” on top of one another or attack cards, such that they keep stockpiling (2->4->6->8…) stacks, similar to the rules of UNO. To address this confusion, we enhanced the rulebook by providing a denoted “Note” section which addresses these edge case scenarios.

Player 4: “The rulebook is a bit long. Some card’s functionality could be clearer”

Response to Player 4: Based on this feedback we have shortened the length of the rule book (from original length = 6 pages → new length = 4 pages). In addition, we have improved the text to be more concise, to facilitate better understanding for the player. To improve understanding of the functionality of the cards in the game, we have added clarifications to address some potential edge cases that came out during playtesting and clarified the language on the cards.

In terms of the design of the cards, we prioritized inclusion and accessibility throughout the entire design process—from the initial prototyping stage to the final product. For example, our game is accessible to individuals from socially or economically disadvantaged backgrounds, as many of the components are common, pre-existing items that players are likely to already own. This is why the instructions for the “unique” stacking cards are intentionally open-ended (e.g., “Stack something that starts with a C” or “Stack something blue”) rather than highly specific. More specific prompts could create edge cases—such as when a particular item isn’t available nearby—or exclude players who may not have access to certain items, thus limiting their ability to fully enjoy the game. Additionally, by integrating many pre-owned items into the gameplay, we reduce the number of components that need to be specifically manufactured. This not only lowers overall production costs but also makes the game more affordable compared to those that rely heavily on custom-made parts. Our game requires so few proprietary pieces (and even those—like 3D-printed parts—can be replaced with simple objects such as boxes or rubber balls) that it could easily be adapted into a print-and-play format. This flexibility allows it to take on a more folkloric quality—one that can be widely disseminated and shared, making it more accessible to a broader audience than many commercially packaged games.

Also, due to the relatively high frequency of red-green color blindness in the general population, we replaced an earlier “stack something green” card with a “stack something yellow” card, so that deuteranopic players can more easily distinguish the color from red objects for the “stack something red” card.

From an ethical standpoint, we aimed to minimize potential conflicts during gameplay. As a result, we chose not to include mechanics that involve stealing cards from other players or any actions that could lead to excessive targeting of a single individual. This decision was especially important in reducing the influence of pre-existing biases on the fairness of the game. Even in scenarios where a player is targeted—such as through one of the stack cards—they are still given a fair chance to recover since their fate is not predetermined. The challenge lies in stacking blocks or items, which maintains a level playing field rather than placing them at a significant disadvantage. Overall, we have made deliberate design choices with ethical considerations in mind, ensuring that the impact of biases is minimized and that all players can engage with the game fairly and enjoyably.

Concept Map:

Ideation exploration:

The idea for Kitten Klimb emerged from discussions about how we could reimagine a new type of stacking game—one with a unique advantage that sets it apart from others currently on the market. Most existing games (e.g., Jenga, Uno Stacko, BBnote Stack Attack, etc.) involve players stacking objects of varying sizes and geometries, from regular rectangular blocks to more eccentric shapes like L-shaped or zigzag pieces.

While these games differ in the types of blocks used, they all share a significant drawback: limited potential for experiential learning and a restricted number of iterations, which are key to long-term engagement and fun. Because the blocks in these games are mostly (if not entirely) predetermined, they tend to become repetitive over time. This low ceiling for variation can make the gameplay feel stale, reducing players’ desire to return to the game.

Our game addresses these limitations by offering players a novel stacking experience. Instead of relying on pre-fabricated stacking pieces, we incorporate “around-the-house” objects, adding an element of unpredictability that helps sustain engagement over the long term. Additionally, we drew inspiration from popular card games like Uno and Exploding Kittens, incorporating mechanics that allow players to “attack others,” “reverse the direction of play,” and “remove blocks from the stack.”

Below is our initial ideation of the game, where we envisioned it to offer players a mix of challenge, fellowship, discovery, and sensory engagement.

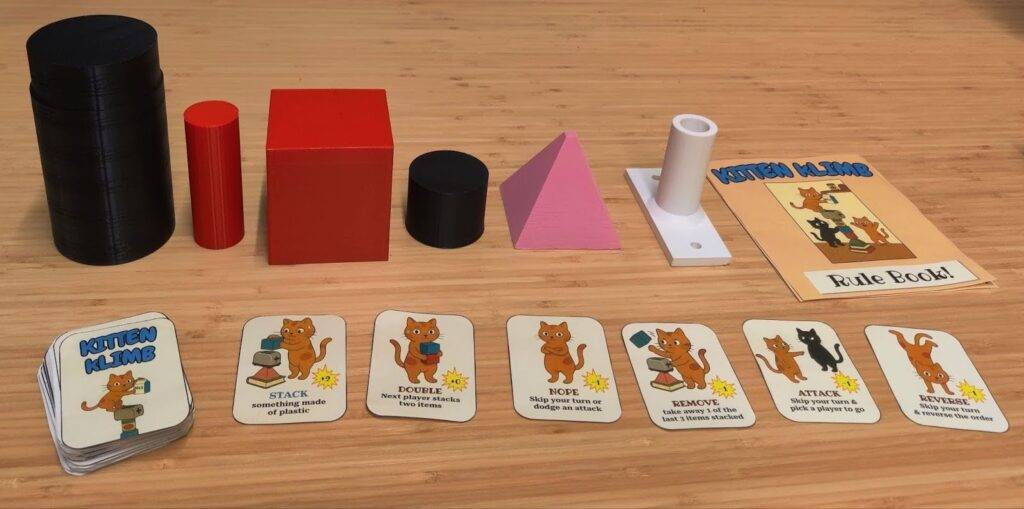

Based on these design ideations, we produced the first playable version of our game for initial playtesting. After four playtests, the game underwent several iterations until we arrived at the final version. We designed and 3D-printed the pre-fabricated pieces using PLA, and printed out the cards, which went through several modifications over the course of the project.

Please see here for our initial mechanics that each member of the team came up with to jumpstart the development of the game.

Initial iteration of formal elements and values:

Our original idea was simply for players to pull stack prompting cards to instruct them on which random household item to stack as fast as they could. As we brainstormed, we decided to incorporate Exploding Kittens and Uno-inspired mods with strategy cards such as attacks, nopes, stack twice, skip, and reverse. This was the first set of mechanics we came up with:

5 mechanics of the game (each dash represents an individual game mechanic).

We can potentially make themed cards (inspired by exploding kittens, maybe use AI-generated images to make it more unpredictable and reduce the types of bias we might put in ), where before a player goes they would pull a card from the top of the deck, and see if they can:

- Skip stacking a block

- Make another pair/ person stack a block for them

- They stack two blocks

- They get to reverse the order of stacking

- Remove and replace a block

Note that block means item:

– We can have two types of blocks, the first can be normal rectangular blocks you get from Jenga, the second set would be a randomized set of items you find from around where you are playing. The cards you draw will state what type of block you get to draw.

– If you draw a random/fun block you have to draw randomly from a bag or something to keep secrecy, you must use the first item you touch.

– Alternatively, if you get the random block card, on the card it will say what type of object to look for in the room in further detail. For example, it could be placed a fun object (“Find anything in the room that is not red”).

– When placing any of the blocks, we can have a casual mode where each turn is not moderated and a competitive mode where the time for each turn will be only 10 seconds long to make the game more interesting

Testing and iteration history:

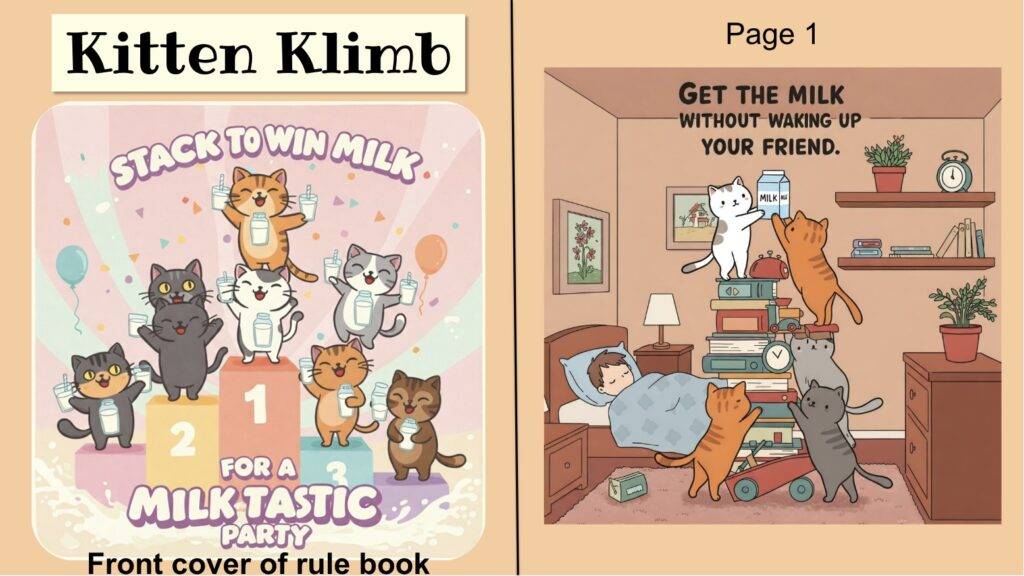

After solidifying the mechanics, dynamics, and aesthetics of our game, we moved on to marketing and developing the game’s narrative. We decided to create a short and simple backstory about a group of kittens competing with each other to build a stack and reach a bottle of milk on the top shelf. The kitten that earns the most points by building the best stack and reaching the milk wins! Based on this backstory, we developed our first set of branding and marketing iterations, as shown below:

Cards

The cards are central to our gameplay experience, so we knew we had to spend a lot of effort getting them right. At first, we discussed our ideas for different cards and knew we wanted a mix of cards that specify a certain thing to be stacked (by describing its material, color, etc.) and strategy cards that let players skip turns, attack other players (by forcing them to take a turn), or dodge attacks. We initially wrote card descriptions on Post-it notes and pieces of construction paper before making an initial set of printed cards with a front and back. These first printed cards each featured a common back with the title and a unique front showing an AI-generated image, card title, and description. We emphasized speed over polish, so we didn’t initially worry about making them look nice, and they accomplished their goal of getting cards into playtesters’ hands.

The issues with our initial deck of cards became obvious almost immediately during the first round of playtesting. We left the list of specific cards kind of ambiguous after our first meeting, so the initial deck had some overlapping cards (in particular, there were separate “skip” cards for skipping turns and “nope” cards for skipping turns and dodging attacks). This confused players during the first playtest, so we told them to treat the cards identically and noted the issue down. The strategy cards and stack cards had different background colors, which helped players differentiate them, but having different titles for the stack cards like “plastic card” for stacking a plastic object and “soft card” for stacking a soft object seemed to create more friction than if they had a common “stack” title with different descriptions.

We weren’t especially concerned about the incongruence between the AI images on the cards since they were an early prototype, but we noted that the clashing styles and excessive detail of the images might be distracting. We also noted that players thought the working title of Milky Stack was odd (it was supposed to reference the narrative of cats stacking items to reach a carton of milk), so we put it on the chopping block.

The most important takeaway from our initial playtests was confusion over the win condition. It felt intuitive that whoever accidentally knocked the tower over had lost the game, but that only eliminates one player. We anticipated this and initially had the winner emerge through serial elimination with more rounds, but this process is slow to produce a winner and means that fewer and fewer of the players can participate, which isn’t very fun. Another option was having players play simultaneously in smaller groups or pairs in a tournament bracket, but this would require additional sets of cards and still involve eliminating players. Some of our playtesters recommended assigning point values to the cards so that once a player knocked over the tower, we could still crown a winner from the number and kinds of cards played during the round.

For the second deck iteration, we tried to address each point of feedback we’d received. We settled on naming the game Kitten Klimb, a punchier title more evocative of scaling a tower. We subsumed the redundant functionality of the “skip” card into the broader “nope” card and unified the visual style of the different cards more. Rather than having different backgrounds, which we felt had overly complicated, distracting designs, we gave them all a plain cream color and distinguished them based on the color of their title (strategy cards having red titles and stack cards having blue titles).

We also added point values to the cards, as recommended by our playtesters, so that each round could have a single identifiable winner. This way all players can tally their scores at the end of a round and then all play again in subsequent rounds rather than eliminating one player each time.

We seemed to converge on a final functionality for all these cards, so the key issue remaining was the visual styling. The typefaces we used were inconsistent with our box art and rulebook, and the style of the cartoon cats in the AI images (while more harmonious than the uncanny 3D-style cats in the first iteration) wasn’t similar enough. Furthermore, the images on the cards didn’t contain any meaning, all having the same content of cats stacking blocks. A player who can’t read the text should ideally be able to tell what kind of card they are holding just from the image on it. The icons on the back of the card (a milk bottle, stack of blocks, pawprint, and Rubix cube standing in for a random object) were also a little out of left field, so we decided to have some more logical imagery.

The final cards have the same functionality as the second iteration but with improved visual styling and layout. To create images with a unified style, we spent a lot of time prompting a free trial of ChatGPT Pro (4o mini model). We were never able to get a perfect match of the style of our box art lid, which had our favorite image, even when providing it to the model as a reference image and telling it to exactly replicate different features of it, but were able to loosely approximate it. Once we got something that still looked appealing, we built on it, re-using the output as a new reference for the model and adjusting the prompts over and over to maintain the same style. The results still didn’t perfectly match, and required many hours of Photoshopping to clean them up (for example, the image generation model had a very hard time maintaining the shape of the cats’ eyes, which seemed to change every time, forcing us to manually edit them).

We ultimately ended up with a unique cartoon cat graphic for each type of card, and a new image of the cats stacking a tower to use for the backs of the cards and the box art. The cards are now readily distinguishable, with the actions of the cartoon cat being directly tied to the card’s text. For example, the “nope” card features a cat crossing their arms, the “reverse” card has a cat doing a handstand, and the “stack” cards show a cat stacking a block on top of a pile featuring not just other blocks, but household items like a book and toaster, as well as the challenging pyramid piece we 3D-printed to include with the game’s default items.

The text on the cards was updated to match the text of the final version of the rulebook and box art, with a unique style for the game title, card titles, and descriptive text. The point values are also highlighted with a bright yellow instead of a light grey, helping guide the players’ eyes to them.

While there’s still room for improvement, we feel our final cards are far ahead of our earlier prototypes, both in visuals and in playability.

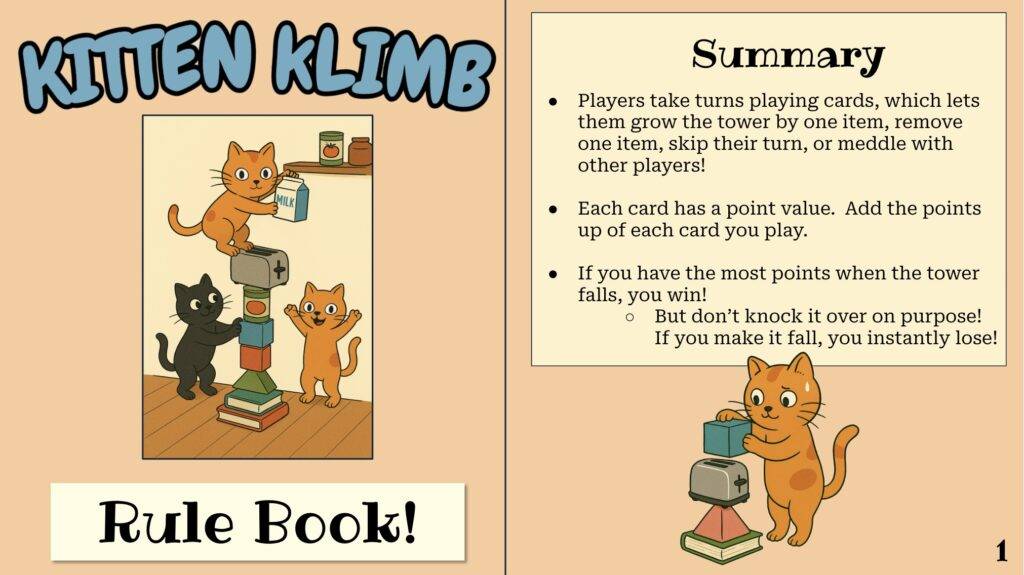

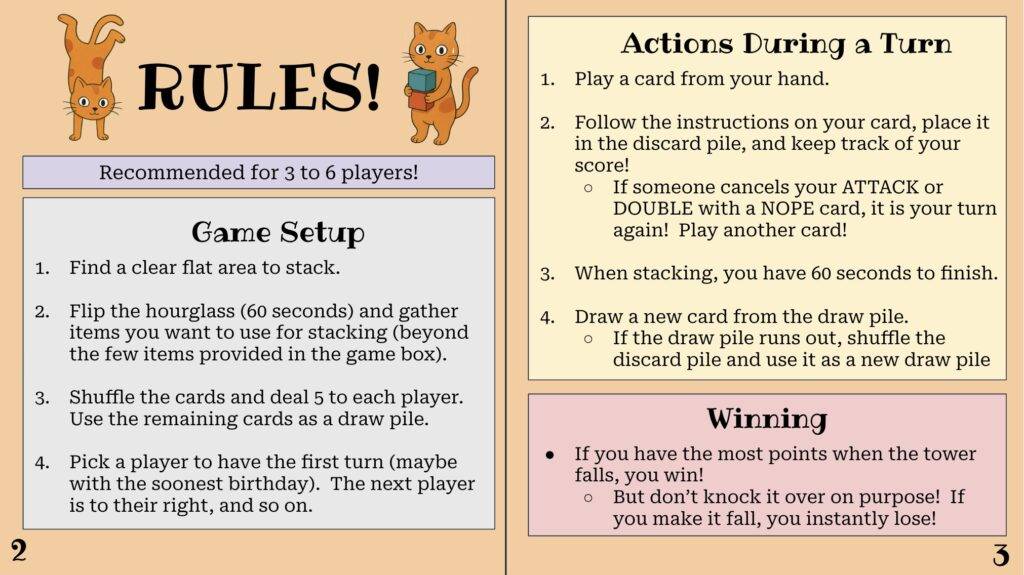

Rulebook

For our original rulebook design, we took inspiration from games like Exploding Kittens which describes each card’s available actions on top of the rules of the game. In the first iteration, the rulebook was organized synchronously to the game-playing experience such that we outlined the setup first, then the actions you can take per turn, and so on. When we presented this edition to our playtesters, they reported being a little overwhelmed by so much text and context without really knowing what the objective of the game was. In our haste to create a rulebook in time for the fourth playtest during class, we left many redundant elements. For example, the game setup steps were listed twice, but with different information, and this delayed the playtesters quite a bit. There was also no general summary of the game, which left them confused about the basic goals of the game and how to play it. In previous playtests before we had a rulebook, introducing the game to players was quick and games were started rapidly. This first, confusing rulebook was worse than having no rulebook at all!

We further noted other redundancies. There was no reason to enumerate the descriptions of the 5 strategy cards because they already contain complete descriptions on the actual cards. The AI-generated images included repeatedly showed groups of cats of clashing visual styles without them containing any information, and they were taking up way too much visual real estate. They were also littered with visual hallucinations (nonsense objects, cats with five or six legs) and nonsense words. The rules were also overly complex, with “remove” cards being dealt to players differently from the other cards due to a miscommunication (all cards, whether stack or strategy cards are supposed to be shuffled and dealt to players randomly).

One of the biggest issues was the story. We wanted the narrative of cats climbing a tower to get milk to be subtle since it’s just intended to be a fun framing device for the game and has no actual impact on the gameplay. But our first rulebook had milk as a very central theme in the AI images, perhaps implying there was some sort of milk-based win condition, which was a large source of confusion.

First Iteration:

From the feedback we received during play testing and our observations, we reorganized and simplified the rulebook. Again, we took inspiration from Exploding Kittens which organized their rulebook from high-level objectives and gameplay to low-level mechanics and details. We replaced the setup that occupied the first couple of pages with a high-level summary to contextualize the following sections that described more in-depth game setup, turn-taking, and win conditions. Since each strategy card already has its mechanic written on it, we eliminated the section describing restating their uses because it felt redundant.

We harmonized the visual styling with the cards and box art, eliminating the large AI images that took up entire pages and using more intensively prompted AI images with extensive manual cleanup in Photoshop.

When someone is learning a new task or a new game, it requires a lot out of your working memory. By streamlining this onboarding process to only include necessary information (from simple to complex info) we minimize unnecessary extraneous cognitive load and keep the new rulebook as short as possible.

Final Iteration:

We play-tested 4 times in section and in class with different unique players each time. With each playtest, we discovered new edge cases and clarification points in the mechanics of the game, while also gaining lots of valuable feedback from the players on their likes and dislikes. For each play-test, we will summarize the main insights.

Insights from our first play test:

Overall, this playtest showed us that our game is possible to execute and there is a lot of fun in the unpredictability and chaos of the tasks.

- We noticed that we needed a better ratio of stacking prompt cards versus strategy cards. During this test, there were too many strategy cards, which resulted in not enough stacking.

- We realized that we need to specify what a valid stack move is… does the player have to place the item on top of the last, or does it have to touch just one side of the tower?

- We decided that we would want some sort of boundary for the tower to fit in, or just require items to go on top of the last stacked item.

- We have both a nope card (dodge an attack or skip your turn) and a skip card. We realized this was redundant and decided to only keep the nope card

- We also received some suggestions for new strategy cards

- where we switch cards between people

- Remove any block from the game

Images from the first playtest:

Second play test:

In this second play test, we didn’t get too much feedback on the mechanics and dynamics of our game, mostly the players faced confusion with elements that are modded from other games like uno.

- A lot of confusion on what a “normal block” was, we meant for that to mean the 3d printed blocks that are a part of the game.

- They were confused at first if only one person can win and lose, this gave us the idea to incorporate a point system where one person loses and the others count up the points on the cards that they played in order to determine the winner.

Images from the second play test:

3rd Playtest:

In this playtest overall, we realized how variable the game can be in terms of fun and difficulty. In the photo, you can see that people started putting small items into the bowl, and they went on like this for a while, making the difficulty low.

- There was confusion on whether the given game blocks were always available to stack, or only when the “normal block” card was played.

- This confusion was solved once we made our game box because we could put them in the box during the playtest to delineate between the two types of stacking items, we changed the wording to “stack a given block from the game box”.

- They were minorly confused about where to start playing again after playing an attack card. But overall they enjoyed using the strategy cards – this would be specified in the rule book

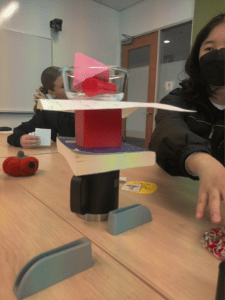

Images from the third playtest:

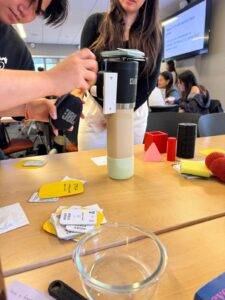

4th Playtest:

After some initial confusion with the general goal of the game and a somewhat normal learning curve for any game, the players really began to enjoy the game. They especially enjoyed playing the strategy cards and making evil moves against other players.

- The biggest takeaways were for our rule book

- We needed to reorder the pages such that the general instructions were first along with procedures and then the specific rules and nitty gritty card explanations would be last.

- We needed to add a general game objective too, like building the tower without making anything fall

- We needed to add more specifications on how certain strategy cards need to be played, like next-person stacks two.

Images from the fourth and final playtest:

1. Players read the rulebook to understand game objectives and card mechanics.

2. Players begin to familiarize themselves with the game and build their tower.

3. One of the players goes on offense and tries to throw off her opponent by stacking the pink pyramid!

4. The next player rebuttals and plays one of her REMOVE cards to take the pink pyramid off the tower.

5. The same player (knowing her next in line opponent doesn’t have another remove card) plays the pink pyramid again!!

6. The next player in line does the impossible and stacks the white 3D-printed block on top of the pink pyramid and the game continues!