If a “walking simulator” really was just a digital recreation of your morning hike, it would probably be a tough sell. No, this unique type of video game has a lot more to offer than a simple stroll. Walking simulators set aside all those fancy mechanics other games use, like leveling and combat, and focus instead on exploration, curating a story told primarily through the traversal of a narratively rich space.

You might be familiar with the typical office setting from your nine-to-five, but I’ll bet you’ve never explored an office quite like the one found in one of my favorite games, The Stanley Parable. Developed by Crows Crows Crows, this intelligent, clever, and captivating walking simulator has made its way onto most major gaming platforms. In this game, you play as Stanley, a desk worker exploring his mysteriously vacant office. The game is rated T for Teen, and would be enjoyed most by gamers who appreciate solitary, meaningful narrative experiences.

The Stanley Parable exemplifies the fact that a walking simulator isn’t really about walking; it’s about where you walk. The stories that walking simulators tell are told through the act of engaging with the space, the story it reveals to you, and the story it doesn’t.

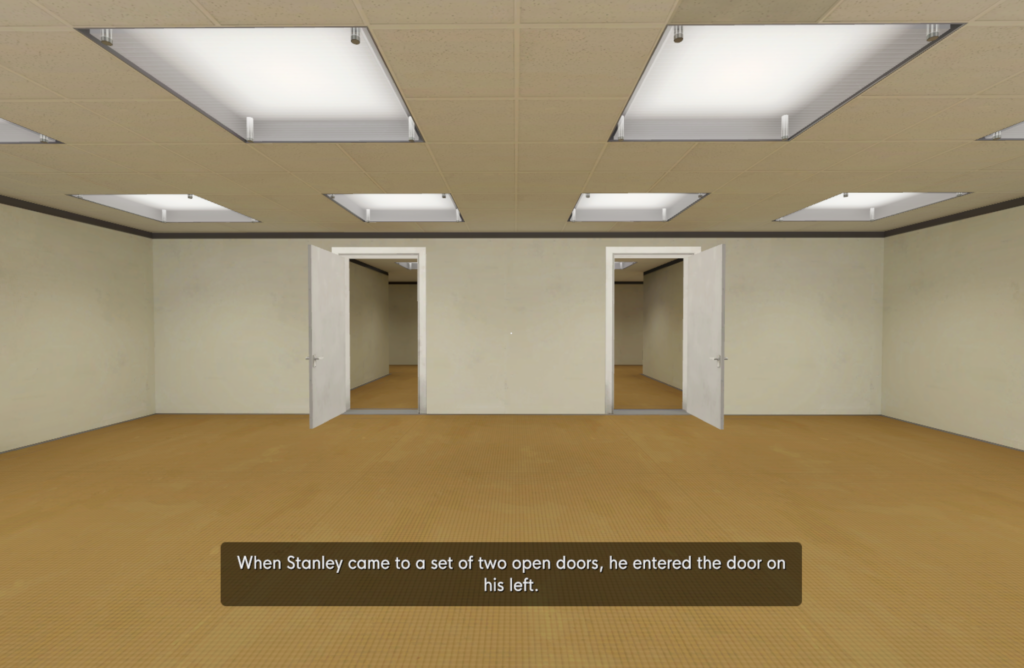

Walking simulators are great at encouraging exploration, and The Stanley Parable does this through its multiple endings. The original game had a whopping 19 different endings, somehow dwarfed by the 42 endings found in the expanded release. There are so many different paths to take that you probably won’t even find all of them, let alone take them. Many of the game’s endings start out the same, but a simple choice forks the story into distinct outcomes. Do that enough times and you get countless alternative routes.

If we think about Bartle’s taxonomy of player types, The Stanley Parable clearly draws in the “Achiever” type of player. After you beat the game in one of so many ways, you respawn at the beginning of the game. This mechanic encourages players to play the game again and again, and Achievers can strive to eventually find all 42 of those endings to master the game completely.

Additionally, the game gives the player so many choices that it almost feels like freedom. There is an extreme illusion of choice in The Stanley Parable to the point that it really feels like you’re exploring the office on your own rather than iterating through the different combinations of choices one could make to reach the end of the game. Designing the game this way is emblematic of the “enacting stories” narrative architecture. Each ending is a little micro-narrative offering something unique, and the game tells its story by making you a part of it. While the story is ultimately on rails, it can’t progress without the player making a decision within the game.

Something else that makes The Stanley Parable an incredible walking simulator is how it tells its story. Sometimes, the story is right there in front of you. The Stanley Parable is famous for its whimsical, omnipresent narrator who describes what you are doing in the game as it’s happening. However, the version of the story the narrator thinks is going to happen is but one tiny fraction of everything this game has to offer. The majority of this game’s narrative is hidden in places the narrator doesn’t tell you to go. It is when you wander off the beaten path that you unlock all that lies hidden in this game. While Bartle’s “Achievers” may not rest until all endings are found, the “Explorers” among us will get plenty of enjoyment out of whatever percentage of the game we get to explore. As an Explorer myself, I think the true magic of this game is not a sense of achievement, but the little moments of subtle yet artfully jaw-dropping awe when you find one of the countless nooks and crannies where the developers left something for you to find. It’s really the “embedded narratives” architecture that makes the best walking simulators so great. The developers put a lot of care into hiding delightful little nuggets of story all over the place for us to enjoy discovering. While I certainly liked the story The Stanley Parable has to tell, I enjoyed looking around for and finding that story even more.

From a design perspective, concealing the finite nature of the game feels crucial. The game has very few achievements, and doesn’t help you keep track of all the endings. I think this is genius, but I am an Explorer type. I don’t want to know the bounds of my playing environment. I don’t want to know when there’s nothing left to explore. If the designers wanted to encourage Achievers, perhaps they might include an achievement for each ending to help players keep track. This is not my suggestion per se; I’m just highlighting a way that the designers could encourage a more Achievement-focused kind of play if they want to attract those players.

The game excels not only at crafting an interesting story but also at delivering it. The narrator is an expert storyteller, with an engaging tone of voice, a dramatic flair, and a dry sense of humor. There were several moments in my last playthrough where I was chuckling in my seat at something funny the narrator said to me. Sometimes, I do wonder if other players had a different experience playing this game. For the sake of spoilers, I won’t say too much here, but there is a point in The Stanley Parable where the narrator is mad at the player for being irrational. The narrator starts verbally harassing Stanley, mocking him and making up rumors to make Stanley feel ashamed. My guess is that most players will find it funny that they’ve flustered the narrator into making these remarks, but the narrator’s words are, in fact, insults disarmed by context. Some players could take those insults to heart more than the developers intended.

Games that insult the player or their character are controversial. While the mocking might be humorous to some players, it also normalizes comments that are quite hurtful if said in the real world. Portal 2 was criticized years ago for an in-game character’s insults, which were very similar to those spoken by the narrator in The Stanley Parable.

The game is rated T; in theory, younger children shouldn’t be exposed to this game. Still, it’s important to consider who might be listening to the messages that your game is sending and how those players might receive them. This goes for all games, not just walking simulators.