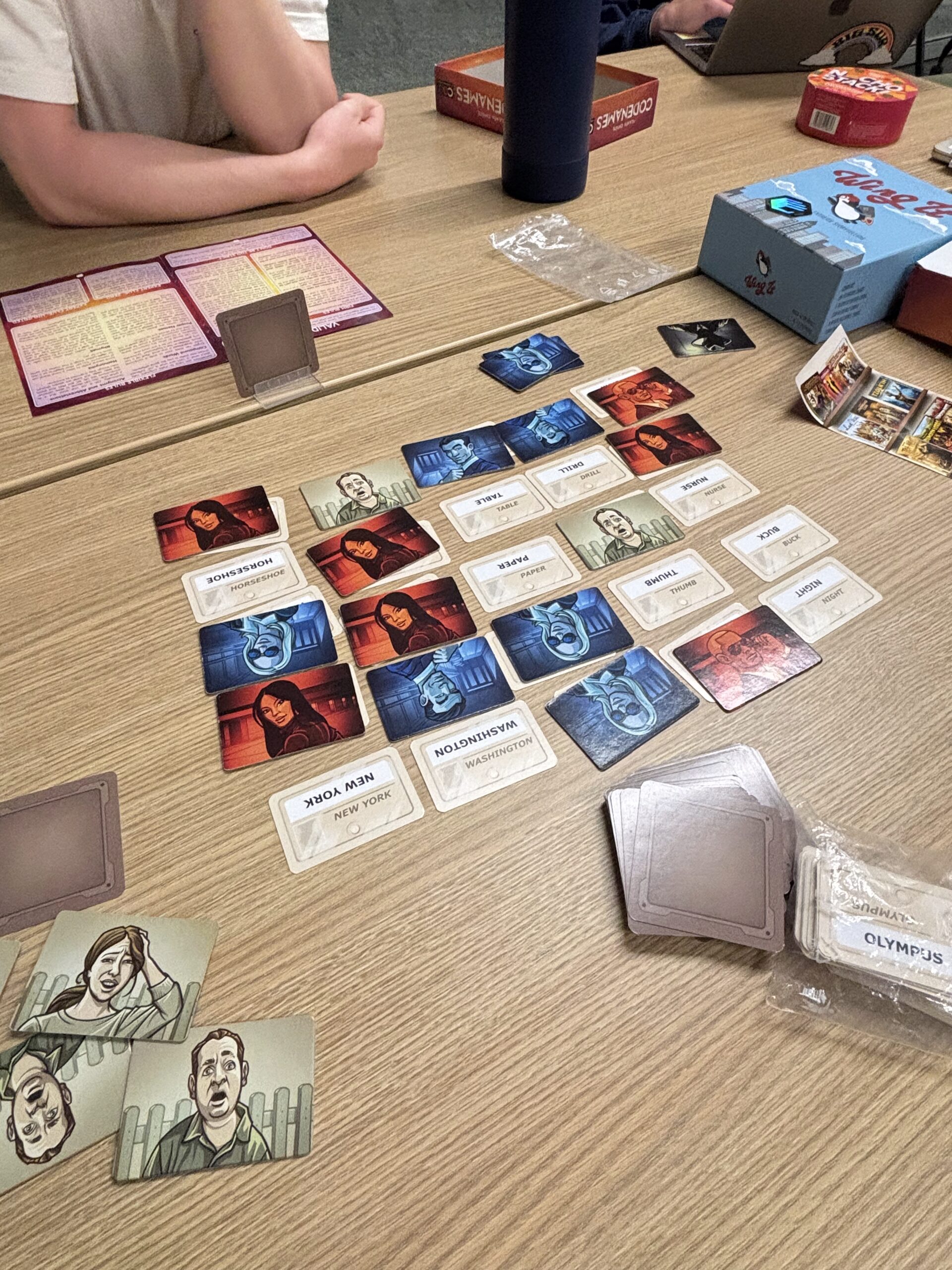

The game I chose to play is Codenames, a competitive board game designed by Vlaada Chvátil. The game can be played both physically or digitally on mobile devices. I opted for the physical version, which made the game-playing experience immersive. The intended audience of this game is friends, family, and even strangers, as the game thrives around social interaction. It’s also recommended for ages 14+ due to the need for abstract thinking and wordplay. Ideally, it’s played with 4 or more players because of the game’s social nature and reliance on teamwork.

In Codenames, players split into two teams, with each team having a “spymaster” and “field operatives.” Teams take turns as their spymaster gives one-word clues followed by a number that represents how many words relate to that clue (e.g., “Country: 2”). The field operatives then try to guess the correct words based on the clue. If they guess correctly, the word is covered with their team’s agent card. However, an incorrect guess either reveals a neutral word (the bystander card), reveals the opposing team’s card, or reveals the assassin, which results in an instant loss. The first team that identifies all its agents wins.

In our game Filibuster, which is a social storytelling game, one player (the Filibuster) is secretly assigned a word with a specific point value. Their goal is to weave that word into a story in a way that’s natural and without making it too obvious to the other players. While the filibuster is telling their story, the other players are trying to guess what the word is. In essence, both games are “guessing games,” but Filibuster is less about precision and more about performance. Instead of relying on minimal clues like in Codenames, players are encouraged to expand and disguise meaning through narrative.

Through playing the game, I discovered that Codenames is the perfect balance of structure and openness, giving enough rules to guide play while letting team dynamics and creativity shape the outcome. This flexibility invites participation across different communication styles, personalities, and gameplay experience, making the game an exciting experience for all its players.

I played this game during game night on Monday with one of my group members (Evan) and two CAs (Amy and Pannisy). As we were playing, Amy explained how you can take a unique and creative approach to giving out clues when you know the other person and how they think. That idea really stuck with me throughout the game. The more I paid attention to how people gave clues or interpreted them, the more I felt like I was learning about how they think. For example, knowing what kinds of connections they make, how literal or abstract they are, and how much they trust their teammate to take a leap of faith. Most notably, in the final round of the game, Evan and I had to get two words or else Amy and Pannisy would win in the next round. Evan gave me the clue “Monster: 2.” The first word was obviously loch ness, but I knew by the way he emphasized the “m” that the second word was “mug,” and we won the game! It felt like the game became less about using straightforward, logical clues to win and more about who could tune into the other’s brain better, which made it way more fun.

Moreover, one of the most interesting parts of playing Codenames was realizing how open-ended a single-word clue can be. During the game, there were moments where someone would give a clue, and it could genuinely lead to three or four different words depending on how you looked at it. For example, Amy gave the word “Miami” and it related to 4 other words. At first, that ambiguity felt frustrating and stressful to interpret. It was like there was a “right” answer I just wasn’t getting. But over time, I started to enjoy that part of it. It made me realize how different people make connections, and how much interpretation goes into even the simplest clues.

The mechanics (limited one-word clues and team guessing) created dynamics that rewarded unique interpretations and shared logic, which led to an aesthetic experience of fellowship and challenge. What really stuck with me was the space for different kinds of thinking. Some people were super abstract, others were more literal, and everyone brought a different approach to clue-giving or interpretation. That kind of flexibility made the game more fun, but it also made it feel more personal. This is what games are. Codenames is not rigidly constructed, so it is unlimited in interpretation and different types of gameplay, making it successful in its goal as a game. I want to bring that same energy into Filibuster. The situations/prompts we use should give players just enough direction to get started, but still leave room for people to take it in totally different directions depending on their personality, sense of humor, or storytelling style. This gameplay really made me realize that designing a game is not just about designing something that works, instead, it’s about creating space for connection, surprise, and creativity.

Codenames and Filibuster both play with language and communication, but in different ways. Codenames is largely centered around precision because players need to choose the one right word that will connect to just the right ideas. Moreover, they also need to trust their teammates to interpret their clues in the right way. It’s strategic and relies heavily on shared knowledge/understanding between teammates. On the other hand, Filibuster leans into storytelling, performance, and individual competition. You’re still trying to get people to guess a word, but instead of narrowing language down, you’re expanding it by building a narrative, choosing what to emphasize, and throwing others off with intentional misdirection. Both games rely on social dynamics, but in Codenames, the tension comes from ambiguity. In contrast, in Filibuster, it comes from how you perform and how others interpret your delivery. The mechanics are different, but they both have competitive dynamics and highlight how playful and unpredictable language can be when it’s filtered through physical interactions.

As an ethical consideration, Codenames and Filibuster both rely heavily on language, which means bias can surface through the clues or stories players choose. Word associations may unintentionally reinforce stereotypes or exclude players who don’t share the same cultural background. For example, providing a situation where the speaker is in a foreign country could unintentionally reinforce stereotypes about natives from the foreign country. This would not only normalize ethnic and cultural stereotyping but it would also humorize a pressing issue. Thus, it’s important to design and facilitate these games in a way that promotes inclusivity, avoids harmful associations, and creates a respectful space for all players.