For my first critical play, I chose to play a bluffing game called Coup. Coup is a card game which was created by Rikki Tahta. Tahta was previously banker and used to play poker with his finance bros, but chose to create Coup after his experience of winning money off of his colleagues. He boils games to their essence and makes games where there is no “general” playing time, but rather makes each move extremely high stakes. The target audience for Coup is usually families or friends since it requires people to be comfortable lying to each other. It is also encouraged for children who are over 14 to play the game, because players need to reason between roles and play strategically while also interacting with words on the manual card.

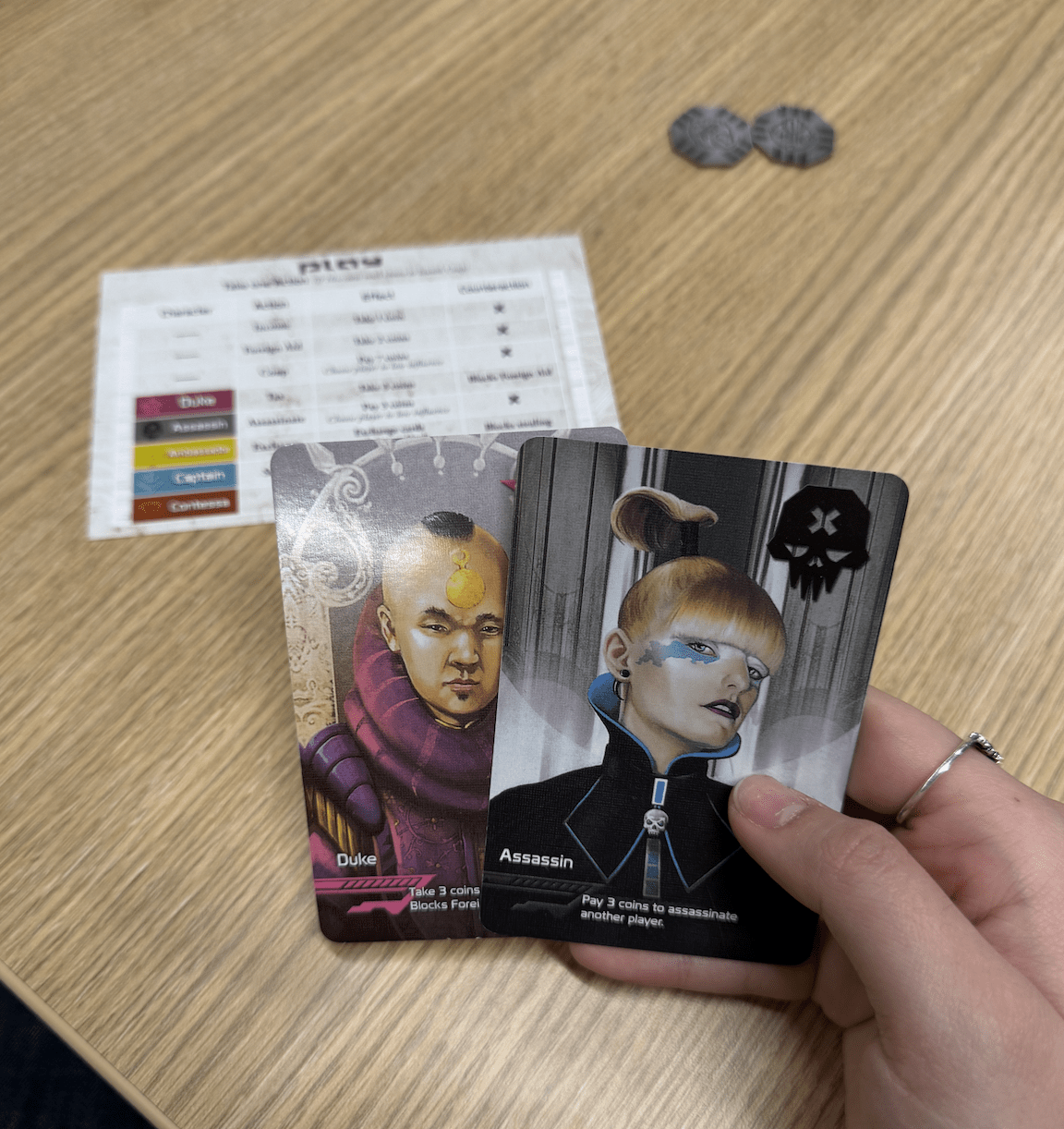

This was my first time playing Coup, and it made me realize that I am a pretty head-on person. I really liked to eliminate people immediately from the game (oops), and my decision-making is oftentimes pretty rushed. I’ve also noticed that my communication style becomes quieter, and I don’t speak out my thoughts. I think this has to do with the fact that I don’t feel comfortable lying and I thought that someone would immediately find out if I chose to be the Assassin versus the Duke for example. I also became very competitive, and I could tell that my competitiveness was heightened when I began to stare intently at my opponents (oops again!). The mechanics of Coup are extremely simple. You have three cards of each role, such as Duke, and you have coins. You also have a manual card which explains what each role can or cannot do, alongside non-role tricks that you can choose to do at any time. The mechanics of the coins is really interesting because once you reach 10 coins, you need to coup, or eliminate someone’s card from the game. This forced “couping” creates an interesting dynamic where the game pushes people to fight one another actively instead of passively. This thus heightens the overall intensity of the game and leads to the ultimate aesthetic of challenge and even sensation, which could occur when people start shouting at one another.

One interesting instance in which the mechanics of the game caused me to lose the entire game was through the idea of calling someone out if I thought they were lying. One of the players chose to assassinate me, meaning that I would have to give up one card. However, I decided to contest their assassination because I did not believe that they were an Assassin. Unfortunately, they actually did have an Assassin card, causing me to lose both my cards.

This idea of contestation adds an extra layer onto the game where people are able to get away with lying because the potential cost of exposing them is incredibly high. This thus challenges the idea that lying in a game is always easy to contest and challenge, because oftentimes letting someone get away with lying might actually be better for our own situation. This means that lying is not a wrong action in games, but rather acceptable because it is a part of strategy making. I believe that the reason why it is okay for us to lie to our friends in games is because there is no stake involved when we lie. We do not lie about actual events in our social relationships, but we are lying in this fantasy world. This reminds me of the idea of the Magic Circle, where everything we do and say belongs to the game only. This therefore makes lying acceptable. Furthermore, in the reading about “What Games Are and Aren’t”, the author talks about the idea of games being spaces where people are able to exist without consequences. Similarly, lying is an action that people can do in games without consequences. Since there is this shared belief that we will all be lying in the game, it seemingly becomes okay to lie, because we are all doing it. However, if one person chose to lie knowing that it is not allowed to lie in the game, then I believe that it would not be appropriate to lie in that instance.

One way in which Coup could be improved would be for people to contest each other more. For example, in one round, most of the players barely chose to contest one another, but just chose to continue gathering coins. This reduces the intensity of the game and does not achieve the aesthetic of challenge. One way of promoting this aesthetic would be to have players contest someone as soon as they reach 4 coins for example. Similar to the way players must coup when they reach 10, forcing people to contest will increase the bluffing within the game and thus raise the stakes. Nonetheless, Coup achieves the incentive of making players want to play multiple rounds because each round is so short. This is a smart design choice because long games are known to become more boring for players. For example, a game like Among Us might be considerably longer because a lot more people have to be eliminated and debating times might take ages to resolve!