The atmosphere of this game hit me full-force the moment I first opened it, saw that the New Game option was greyed out and my only option was to Continue, and second-guessed for a moment whether I had, in fact, played this game before. It had certainly been on my list for a long time— maybe I had downloaded it and since forgotten? I thought I’d watched a clip of the intro on YouTube once before, but… maybe I’d actually played it myself?

I reminded myself that no, I couldn’t have played it before— I know I just purchased it a few minutes ago. But it was enough to set me off-kilter right from the start.

It took less than a single run for me to fall head-over-heels in love with Inscryption. Admittedly, my opinion of it was destined to be biased, as I’ve half-joked to my friends that it feels like this game was designed specifically for me (someone who’s loved card games, death games, horror games, and horror-themed card games with deadly stakes ever since my childhood Yu-Gi-Oh! obsession that never ended). It was a unique form of torture playing it for the first time in a room with a friend who didn’t want spoilers, forced to bite my tongue and keep my reactions vague as brick after atmospheric brick hit me in the gut.

I was continually impressed with how effectively each little design choice came together to disorient the player. The first section of the game takes place in a claustrophobic cabin barely a few strides across, but it’s so dimly lit that its corners are perpetually shrouded in darkness; when you sit at the table, you can’t see past the edge of it. You may walk the room freely, but move only in jarring bursts at harsh right angles as if stumbling on shaky legs. You’re alone with a single NPC (not counting the sentient cards), but you don’t know his name and he doesn’t bother with yours (at least, not at first), and most of the time you can see nothing of him but his eyes. He speaks as if you’ve been here before, and the game’s UI suggests this as well, but no flashbacks are offered in explanation. Such a limited setting should in theory be easy to understand and master, but everywhere you look, the details are just a bit too hazy to get your metaphorical feet underneath you.

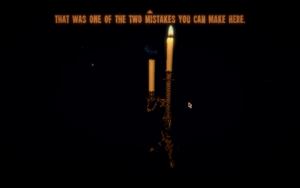

I also adored the way Inscryption instills dread through player agency. The first time you lose a game to Leshy, he orders you to get up from the table and fetch him the candlestick from across the room. He doesn’t tell you what will happen once you do, but given the circumstances, you’re sure it can’t be good. You don’t want to find out. What if you just refuse? This isn’t a cutscene; you have control of your legs, you may wander the room for as long as you wish, or even choose never to sit back down at all. Leshy won’t force you. But you’re trapped in the cabin, and nothing will change until you do what he asks— so you swallow down the pit in your stomach and bring him the candles. When you do, he snuffs one out and says:

This weaponization of agency is laced throughout the game. The pliers will help you in a pinch, and you’ll never be forced to use them, but in desperate times a point is a point, even if the red-flashing screen and ringing in your ears protest your willing choice. Once, after you lose the game and Leshy is preparing to sacrifice you, he wonders where his camera has gone. From where you lay half-dead on the floor, you can see it there next to you, within arm’s reach. You don’t want to help him; once he’s taken his commemorative photo, he’s going to kill you. But what else can you do? There’s nothing left for you now, you can barely move, and there’s no point prolonging the inevitable. So you click on the camera to pick it up, and turn to Leshy and click on him to hand it over, every step carried out by your own hands. (He thanks you, and kills you.)

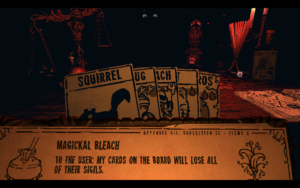

This dread is only compounded by the player’s feeling of powerlessness, brought about not only by the disorienting atmosphere but also the sense that every in-card-game victory is entirely within Leshy’s design. He isn’t upset when you cut up his cards, because he gave you the scissors; when you discover powerful cards hidden around the shack, he lets you use them without complaint; the rulebook is written from “I” to “you” by Leshy himself. Even the way his dialogue appears as captions on the screen with no name to label it or bubble to contain it drives in the feeling that it isn’t merely your opponent speaking— it’s the narrator, the voice of the game itself, your god in this cabin. No matter how well you perform at his game, you haven’t taken any real control, because it’s still his game.

I haven’t yet finished the cabin section of Inscryption, but I look forward to completing it and seeing what the game’s other sections have to offer. I also look forward to forcing my friends to listen to me talk about this game forever and ever.