For my critical play, I decided to play “Oh Hell,” a card game created in the 1930s by B.C. Westfall (the exact origin of the game is unknown, but Westfall is credited with being the first “descriptor of the game”). I played this game on “Cardgames.io” (an online website, with pre-programmed players – not in real time). The target audience is realistically similar to that of Poker – ages 15+, due to the more analytical and gambling nature of the game.

The combination in which this game incorporates luck – both in its original mechanics and in the dynamics that it creates – may lead to an addicting game.

In a previous reading, we read about interaction loops and how we might repeat the same round or other rounds in order to improve our skill. In more social gambling games like “Oh Hell” or Poker, the motivation of why a player replays a game is less clear cut. Arguably, there is some skill to playing these games. Specifically, in “Oh Hell,” you are able to see your deck before you bet the number of points you win – you start to learn that you should bet no greater than the number of “trump” cards in your hand. There is a certain aspect of skill connected to the number of rounds you win as well, for instance, you can hold a higher card either to purposefully win or lose a round. However, unlike more classic win or lose games, the reward is not directly tied to the outcome of the game. In “Oh Hell,” even if you win many rounds, if you don’t win the exact number of the rounds that you had originally bet, then you still lose the game. The success of these games lies in something slightly external to the game mechanic itself.

There is something unique about these social gambling games like “Oh Hell” and Poker, in comparison to more machine vs player gambling games like Slots. When you incorporate a social dynamic into a gambling game, you also embed an additional layer of luck and randomness. This randomness partially comes from the social aspect of the game – you decide how much you bet based on other players’ guesses, body language, and confidence. There is an art to deception in these games, that pure skill and knowledge of the game mechanic cannot replicate. For example, I could purposefully bet to make someone else lose in Oh Hell. Part of its game mechanic is that the sum of guesses cannot equal the total number of rounds thus at least one person is destined to not win the number rounds that they had initially bet.

(pictured above, if you are the first player to choose, then you can choose any number to bet)

Then during the actual gameplay, the probability of you winning hinges on the quality of your deck in comparison to the quality of the other players’ deck (something which you cannot predict, because all 52 cards are in play).

The balance between randomness and skill to win ultimately create the addictive nature of the game. This leads us back to the motivation as to why a player will play the same game multiple times.

In the Game Balance Lecture (6B), we learned that luck has the capacity to take control away from the player and deemphasize skill, all while creating unexpected outcomes. In Oh Hell, you could have two players with the same strategy and relatively similar skill levels, but one could win significantly more times than the other. The balance here between skill and randomness is crucial to creating an addictive game. If the game skewed heavily towards solely the skill of the player, then the player would follow a more interaction loop pattern of learning the game – at some point it would be easy for them to navigate through games and arguably less likely for them to replay the game once they’ve reached mastery. If the game skews heavily towards luck and randomness (in games like Slots), then the player can be discouraged (if the luck does not “go their way”) or be dangerously enthralled by the thrill of winning (if luck somehow goes their way).

In more balanced games, players may alternate the reason as to why they lose or win a game. The player could think that it was due to bad luck (in the case of Oh Hell, maybe they get the last bid and have a greater challenge of achieving their bet), or due to poor strategy (maybe they played the wrong card at the wrong time). In either case (and because both are almost equally possible), the player is more inclined to keep playing rounds in hopes that the next round changes. This is where the randomness comes into play, because a player’s decision to keep playing can hinge on either of these reasons – if they win, then they are even more likely to attribute it to their growing skill as a player and continue to play.

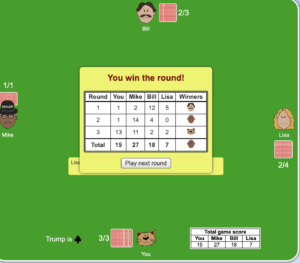

There’s a false sense of growth in these gambling games – if I play more, then I become a better player. The few times you actually win overshadow the times that you lose, with one attributing their wins to skill and their losses to bad luck. Oh Hell itself is made up of separate rounds and because of the duration of each round, it’s easy for each round to feel like its own little game. All it really takes is winning one round and it feels like I’m improving as a player. In the case of balanced games like Oh Hell, I find myself thinking that even if I have one bad game that I can slightly change my strategy and find better luck.

(pictured above, me winning one round after losing the previous two rounds)

This is greatly what I experienced playing Oh Hell – it’s quite an addictive game, due to the ability to believe that with more times you play, the better of a player you become. I don’t have many critiques of the game itself, but mainly that the mechanic of who gets to bet first is also random. This makes it more likely for me to say that the person winning is probably going to be the person who goes first. Additionally, once you begin to trail behind in points, it’s virtually impossible to make up the difference in the remaining rounds, so your motivation is no longer to win yourself but instead to make others lose (which is an interesting phenomenon in itself).

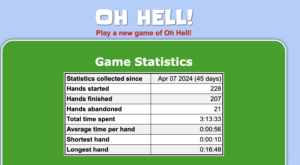

(pictured below, the proof that this game is addicting, with the amount of time that I’ve spent on it – each hand is a game. Interesting to note the number of abandoned hands, which is when I feel like I’m going to lose or I’m too far from winning the game, but I believe that I will have better luck next game)