For my critical play, I chose Journey, a video game developed by Thatgamecompany for general audiences. Journey uses movement – how the player moves, the speed at which they move, and what they move through and past – as a key component in telling its story and communicating its themes. One of the first things that a player will notice upon starting their journey is that the player character is very slow, and anything interesting looking is quite far away. By forcing the player to walk through its environments at a (relatively) slow pace, Journey inflates their perceived size in the player’s mind. This also provides a greater contrast with the times when the player is permitted to move fast, making those feel far more triumphant.

That said, the level design and movement speed form a happy balance where everything is far away, but nothing is too far away. By making sure that there’s always just a few things within a convenient distance, Journey keeps the player moving, preventing them from feeling lost or stuck while keeping them from getting overwhelmed. Combined with the subtle ways that the wind and slopes of the terrain speed you up when you’re going the right way and slow you to a standstill when you try to leave the map, this creates an incredibly natural-feeling but effective system for keeping the player on track.

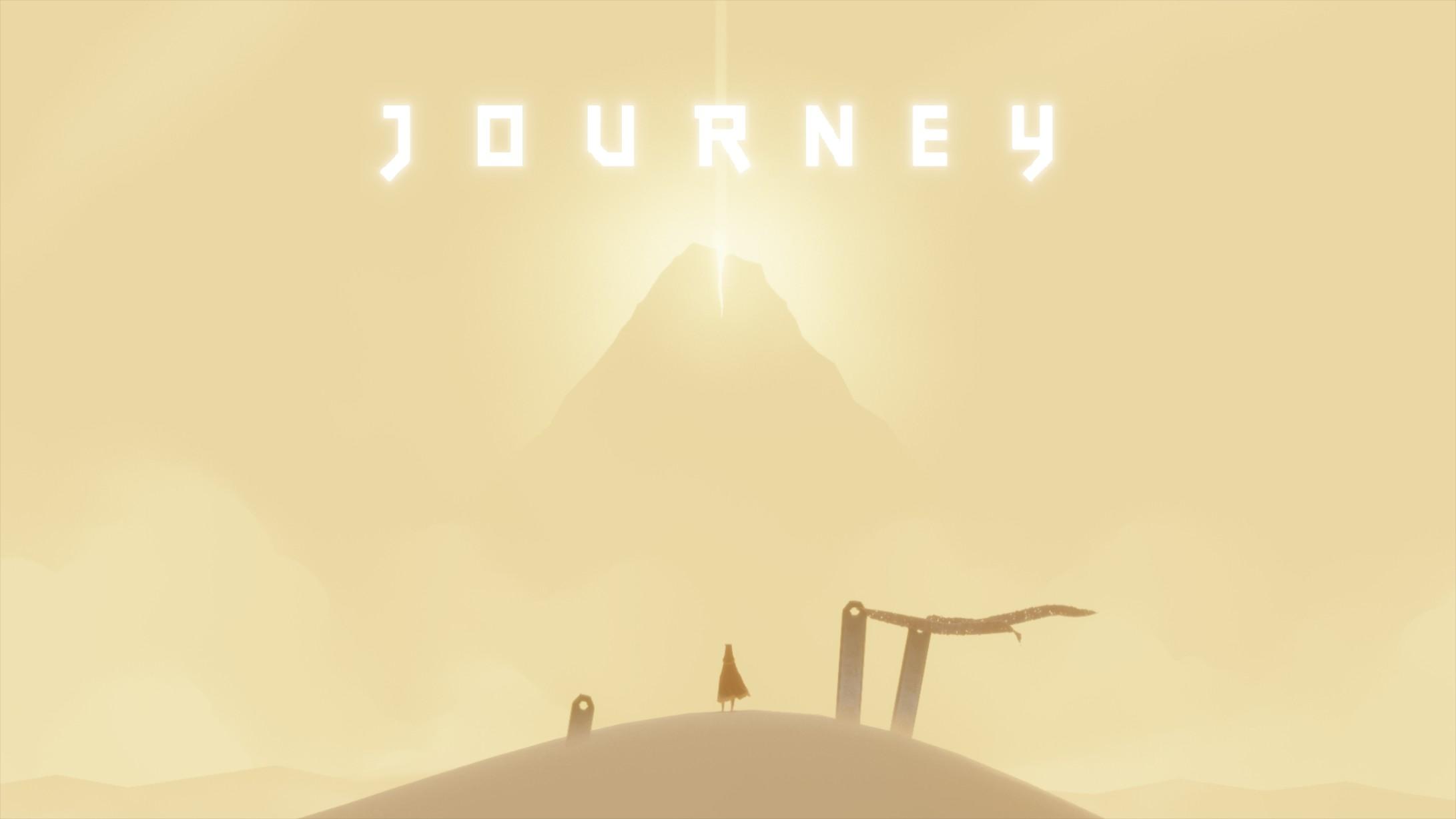

Pictured: the wind serving as a less artificial-feeling stand-in for an invisible wall.

I’d go so far as to say that this ties into Journey’s themes quite effectively. While I wasn’t able to glean an in-depth understanding of the game’s lore from the short time I played, I got the impression that the importance of not caging in nature’s magic was one of the core themes of the narrative, insofar as such existed. Such a story would not be well told through narrow corridors and obstructive walls; being pulled along by the inertia of intuitive level design fits it far better.

The walls and corridors we do see also associate neatly with this text’s theme of movement. If I had to choose one game developer buzzword to summarize my point here, it would be “environmental storytelling.” We walk over, past, and through the ruins of some manner of lost civilization, and in doing so we are given the time to properly consider them. Indeed, we hardly have a choice- our other option is to look out into the endless sands. By making us take our time, the game communicates to us that our purpose here is to think, not just to do.

What puzzles I did encounter, if they could be called that, were also tied into the movement at every point. My constant motive was “I want to walk over there,” and the solution was usually “walk over here first and shout a bit.” Every part of the gameplay process centered walking, looking, and thinking. I could not imagine a better set of constraints to apply to the player if I wanted my game to be interpreted first and foremost as a work of art, rather than a challenge to overcome.

Pictured: a game seemingly optimized for screenshot-sharability. Pictured: I’m still very much a doubter about seamless multiplayer, but I can’t deny that it led to a very cool experience.

Pictured: I’m still very much a doubter about seamless multiplayer, but I can’t deny that it led to a very cool experience.