Babbdi is a first person exploration game created by the Lemaitre Bros in 2022, playable on Linux, macOS, and Windows. This single-player game is suitable for ages 13 and up due to its disconcerting atmosphere and isolating nature, but for enthusiasts of liminal spaces like myself, that uncanny feeling is exactly what makes the game enjoyable.

Central Argument

In Babbdi, walking serves as not just a mode of movement, but a narrative mechanism that unravels the story as the player traverses through the world – that’s because the player starts off with nothing at all, only the introduction and a glimpse at the available movement keys. Hence, Babbdi uses walking to tell the story by treating walking as a mechanism for story discovery, encouraged by limiting information to environmental storytelling (that can only be discovered by walking) and exploration without consequence. Different player choices and exploration pathways lead to unique experiences, appealing to the aesthetics of narrative, expression, and discovery that make the game so captivating.

Environmental Storytelling and Limited Information

In this disconcerting environment of utter solitude where the player is the only moving agent in this still-life game, the only way for the player to advance through is to move.

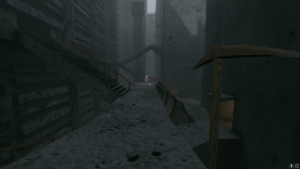

Since Babbdi operates on a single-player versus game structure, the player’s main conflict is the limited information – the player is spawned into a room with two other rooms to walk into, both with NPCs in them with dialogue about escaping that set the scene and goal for the game. This is the last of the guided exploration, and from then on the player understands that the only way to get information and move on with the story is from subtle clues in the immersive environment like billboards and signs, sounds (relative to distance), and interacting with other NPCs. In fact, Babbdi cleverly conveys this with its dull visuals and blocky buildings, yet giving color to NPCs or signs that stick out like a sore thumb. In the picture below, once I got to the outside of the building I spawned in, my eyes were immediately drawn to the NPC lady in pink who I immediately walked to.

As a player, I knew exactly what information to look for in the environment to further my story, indicating that walking was a central mechanic to the narrative. This creates a dynamic of self-driven exploration, in which the player actively seeks information and finds satisfaction from the aesthetic of discovery.

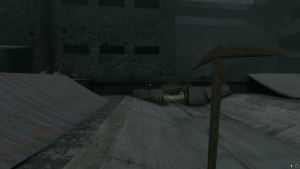

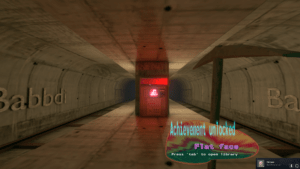

However, one of Babbdi’s most notable features ties back to the limited information that forces the player to explore. Babbdi leverages mechanics like meaningless clues where the player can talk to an NPC or interact with the environment in some way, like crawling through a tiny underground crevice, to reach a dead end or gain no information, as seen in the image below. Unlike games like Pokemon where every item may potentially be of use, the addition of meaningless information creates a dynamic of active engagement and curiosity, where players walk and talk to all in their environment since missing anything could stall the story – directly appealing to the aesthetic of discovery once an actual meaningful clue is found.

However, there is a fine line between forced curiosity and boredom, as these interactions can be mundane and repetitive, such as NPC conversations only being two sentences long. This leads the player to look for shortcuts rather than fully immerse themselves in the intended story of the game.

Exploration without consequence

What I most enjoyed about Babbdi and illustrated the importance of walking to storytelling is the unique narratives each player’s journey is built off of based on the path that they walk, which the game encourages without punishment or failure.

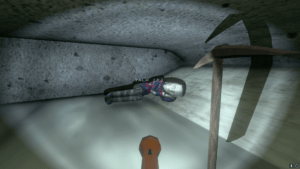

The abundance of exploration tools and mechanics – such as pickaxes for climbing, propellers for flying, flashlights for exploring dark spaces, and the abilities to crouch, jump, and sprint – balances the challenge of limited information in a platform space. The player is practically invincible in their endeavor, as there is no way to die (I got hit by a train and respawned in the same place, as seen below) and there is no fall damage even if you climb to the tallest peak in the game and jump off, which I did in order to find the fastest way down.

True to a walking simulator, you cannot fail any tasks and are forced to repeat it (Clark) , as your story is linear. The only boundaries to the game are the concrete walls surrounding Babbdi that I scaled yet could not escape. A dynamic of player autonomy and empowerment is created as a result, with all players understanding that there are multiple paths to any destination – scale a wall, or do some parkour and jump on concrete slabs instead – which appeals to the aesthetic of expression. Unlike games like Dear Esther with limited movement mechanics, players can either choose to complete Babbdi and walk through their “story” in 40 minutes, or, speedrun it in 4 minutes, which is an achievement in the game. Thus, the resulting narrative is built upon the unique path the player chose to walk, as the player is empowered to create their own story to escape Babbdi.

Points of consideration

Although this was a satisfying game to complete the first time around, I had trouble truly immersing myself into the game and story with such an open-ended yet unguided experience. The boundaries of the game were too unclear for me to cherish the story, with one ending to escaping Babbdi pictured below, and I soon discovered that too much agency led to boredom. Babbdi should take into consideration what elements are truly meaningful to the game and how it is represented to the player – would this be sunlight shining on specific objects crucial to the game? Or, if the player is truly the central agent to the storytelling process with the liberty to walk, shouldn’t the player’s life have more value? Falling off of a building with no consequence definitely made me, as a player, feel removed from the game and decreased the aesthetic of sensation. The player’s choices and story ending currently acts as a means to an end in the game, but I truly wish more emphasis and meaning was given throughout the game to add weight to the aesthetic of discovery.

Works Cited

Clark, Nicole. “A Brief History of the ‘Walking Simulator,’ Gaming’s Most Detested Genre.” Salon, Salon.com, 12 Nov. 2017, www.salon.com/2017/11/11/a-brief-history-of-the-walking-simulator-gamings-most-detested-genre/.