(I remember briefly watching “What Remains of Edith Finch” gameplay back in high school, and I was fascinated by its dark story. I’m really excited that I was reminded of it and can play it for this critical play! I actually finished it and love it.)

“What Remains of Edith Finch” is a game developed by Giant Sparrow and published by Annapurna Interactive in 2017. It’s a single-player, first-person exploration game that takes about two to three hours to complete. The game is available on all platforms including consoles, iOS, and PC, but I played this game on PC (Steam) for my critical play. Due to the mature topics covered, this game is best suited for a player who’s at least a teenager that enjoys immersive, narrative-driven mystery experiences. The game appeals to Collector and Storyteller players because you’re essentially finding pieces of information to create the story.

Central argument: “What Remains of Edith Finch” uses “walking” and exploration to tell its story by creating player-led pacing and immersing them in the environment.

The mechanic of walking allows the game to set a contemplative pace, giving players the time to absorb the atmosphere. While many games have numerous constraints and time-based events (like cutscenes), “What Remains of Edith Finch” gives power to the player to pace themselves. Walking provides the downtime needed to investigate the places that are most confusing or interesting to the individual player. The game’s walking lets you discover the fantasy and narrative.

Especially for a narrative as complex as this game’s, most players will find that they need the self-pacing to revisit areas. While this may seem repetitive, it actually lends itself to a creative way to progress the story. When you revisit certain areas, you’ll often find new pieces of information that you previously missed—it’s clear that the game is designed to force players to walk, get lost, and explore. Additionally, as the story progresses, revisiting old rooms allows the player to make connections that weren’t previously possible. I had so many “ah-ha” moments that motivated me to retrace my steps and say “oh, so that’s what that meant!” You are never just walking in a straight line—you walk in circles, zig-zags, up-and-down, and no matter what, you have a high chance of discovering something that adds to the narrative.

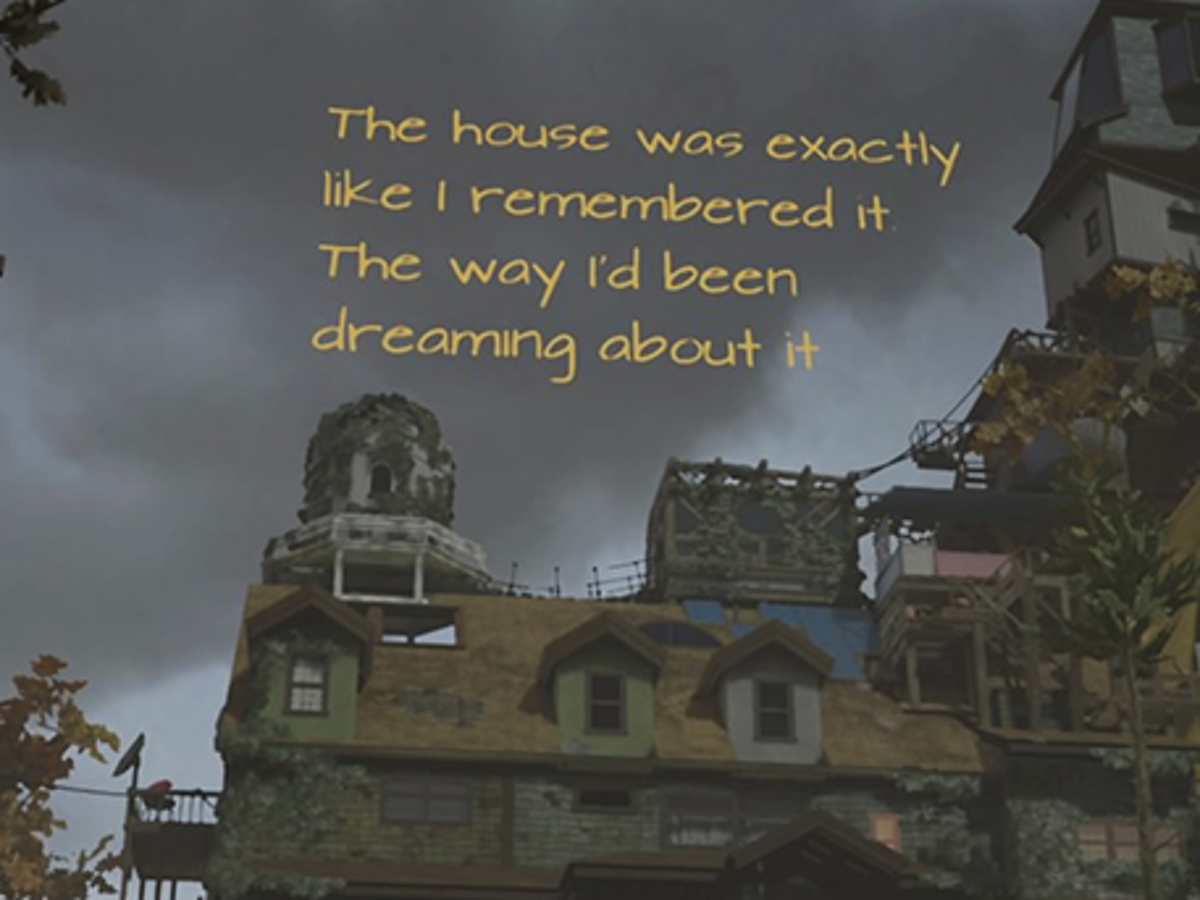

By letting the player walk around the environment, they’re also incentivized to interact with different elements that build the narrative. For example, walking into a certain area triggers text or audio to play, and it’s these hidden nuggets of information that allow the player to piece together the mystery and progress to the next stages. Walking tells the story because the action of walking is complemented by the discovery of information: the story is embedded into the environment, and you literally walk through it. Because “What Remains of Edith Finch” excellently creates an immersive environment through design and artwork, the story progression feels organic and rewarding. The only real constraints are world boundaries and realistic limitations of the player’s body. There are basically no rules, procedures, or resources—it truly is up to the player. Because of this, your mind is only focused on what the game wants you to focus on: navigating the environment and story.

“What Remains of Edith Finch” uses different types of “walking” to tell the story. Throughout the game, the modes of storytelling are constantly shifting, giving the player unique mechanics to work with. For example, after shooting the deer on the hunting trip, you control the walking of the Dad from a third-person perspective, and before that, you control a camera to take photos. Not only does this introduce a novel mechanic into the game, but it adds to the story by clearly delineating that the hunting sequence is a self-contained sub-story in its own “world.” The switch-up in walking style suggests that the player is in a flashback sequence and controlling a different character. Then, when you’re in the comic book sequence, you walk through comic scenes swinging a crutch. Yes, this could have just been shown through a normal first-person perspective, but the style creates an incredibly fun sequence to look at. Also, this new walking aesthetic clearly shows that you’re controlling a different character, and anything you learn about the story is from their perspective.

Although I loved the walking aspect of this game, I believe there were a few areas of improvement in its design. First, the game is not as immersive as it could’ve been because of the camera angles and various “mini-games” that you play throughout. For it to truly exemplify the “walking simulator” genre, I wish it was more open-world and incorporated more elements of first-person, realistic exploration. A lot of the storytelling occurs when the player is not actually walking.

Still, “What Remains of Edith Finch” was a great game, one that met my expectations from when I first saw it back in high school. It’s one of the first walking simulator games I’ve ever played, and it shocked me to see how well a story could be told through a seemingly simple mechanic that has limitless room for creativity.