This week, I attended the CS 247G Game Night where my table group had fun playing two games: Trial by Trolley (TbT) and Two Rooms and a Boom. For this Critical Play, I’ll focus on TbT and comparing and contrasting it to my team’s current iteration of our P1 game.

The Trolley is a social deduction game created by game designer Scott Houser. The game is playable either face-to-face or online on various platforms, including browsers. Because I was at Game Night, I was able to play this game in person. The game is designed for three to thirteen players (we had three players; the game differs by number of rounds with more players, and it also becomes more collaborative, as you get to work with team members). The game is a simple and easy-to-learn party game, but the fact that it involves dark humor (the deaths of friends and all of humanity were discussed when we played) and mature themes (similar to Cards Against Humanity) means that the game’s listed target audience of people aged 14+ is appropriate. These themes also place the game in a role where it is more suitable to be played by people who already know each other, although it is technically playable by any group of players.

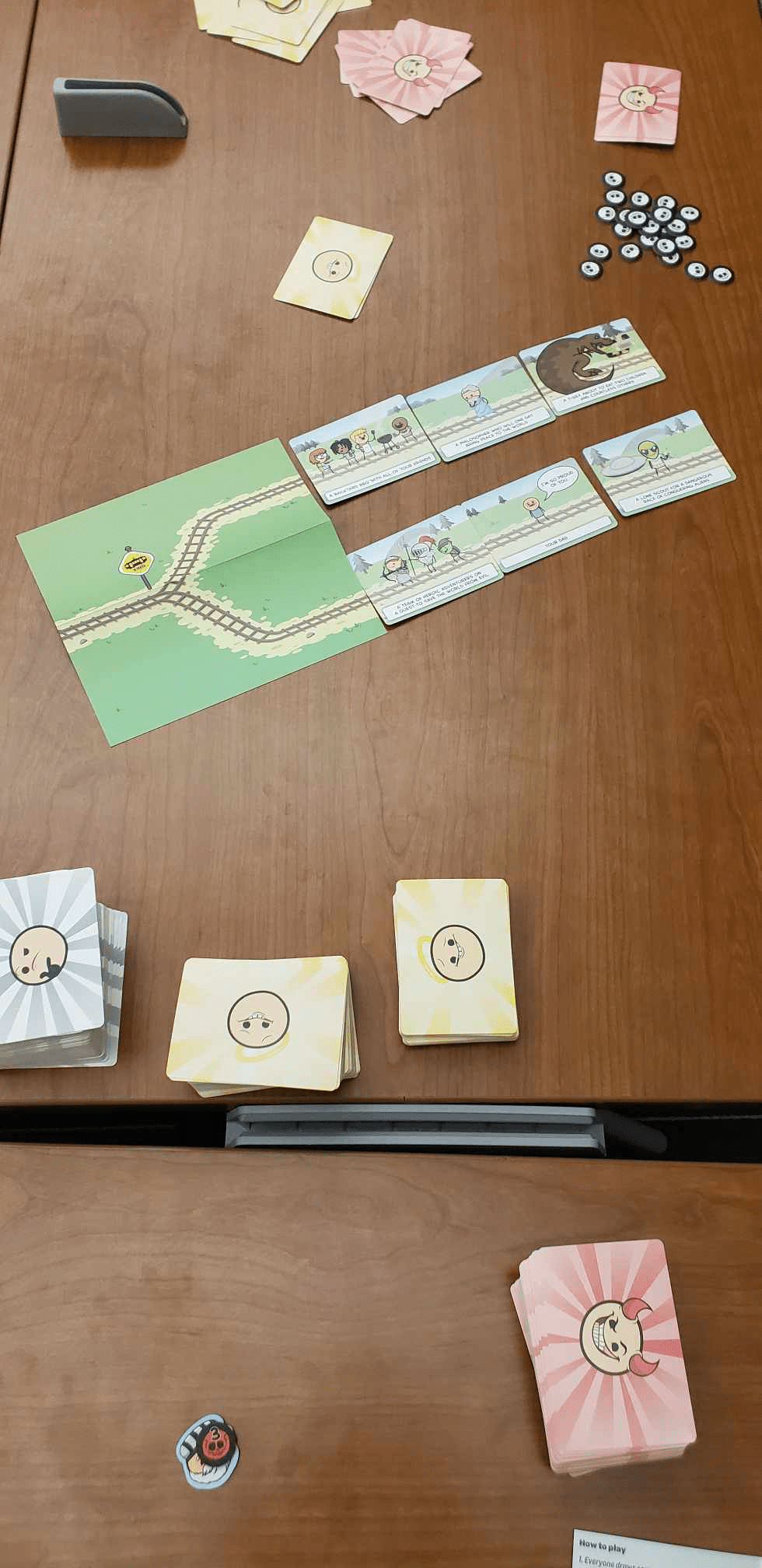

The image below shows the setup of The Trolley. Note the two paths of track, which show how, socially, this game is about arguing against another player.

Currently, my team for 247G is working on a social deduction mod of Jenga (a game in the same category) tentatively called “Stack.” Our game involves players attempting to stack a tower of dice (based on action cards), while a saboteur player attempts to have it fall over (without getting caught) before it reaches a certain height.

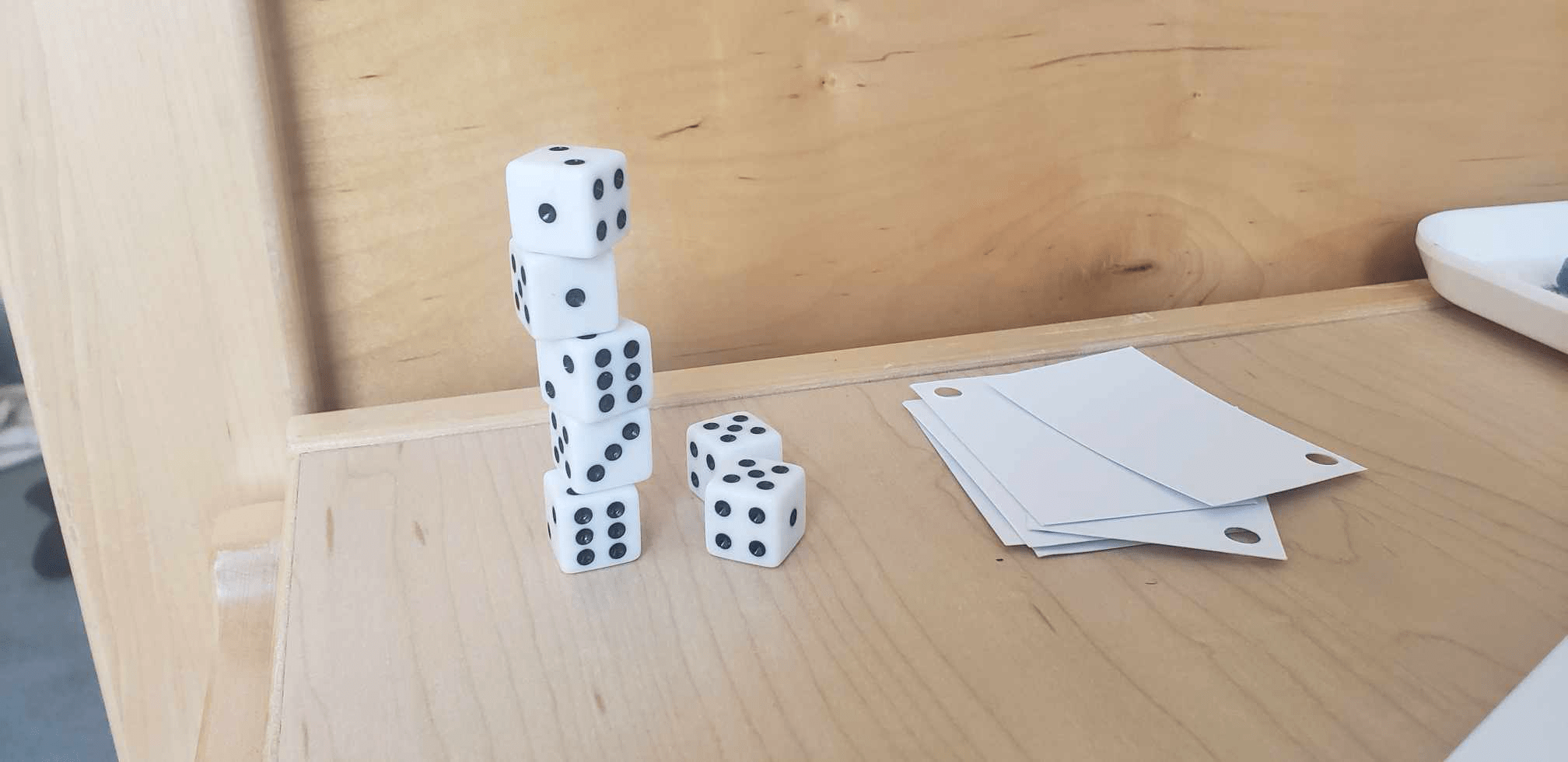

The image below shows the setup of Stack. Note the subtle aspects of how the dice are stacked which show how, socially, this game is about perceiving other players and their actions.

In this Critical Play, I argue that, although both games are party games to get people closer, they achieve this very differently. Specifically, the formal elements and mechanics of TbT result in the game involving more active socialization, whereas the formal elements and mechanics of Stack result in the game involving more perceptive socialization.

Let’s start by looking at what both games have in common. Concerning formal elements, both are table-top games with cards that work with 3–4 players (that’s how many we play-tested them with) (critique: TbT would not really work nicely with 13 players). Both introduce conflict (although TbT’s is more overt), with players having some number of cards as resources on their turn. Technically, both games allow for discussion in their rules (mechanic).

The games immediately begin to differ in formal elements when you look at their objectives and rules. Players win TbT by winning rounds, which is determined by your ability to, given a set of cards you can pick from, out-argue another player in the eyes of a third player (the judge) (critique: judges can vote for players who are behind to keep themselves ahead). On the other hand, players win Stack by stacking the tower or identifying the saboteur (if they’re normal players) or by the tower collapsing at some point without being identified (if they’re saboteurs) (in our game, the saboteurs introduced instability instead of knocking over the tower directly). Already, you can see that what constitutes a “round” of a game is very different (an argument + decision versus everyone performing an action card on the dice tower).

Based on these rules (formal elements + mechanics), you can see that TbT emphasizes a dynamic of discussion (need to speak to win an argument. critique: how do you know the discussion is over?) and getting to know other people’s values (when we played, we asked the judge questions). On the other hand, Stack, despite also allowing for discussion (similar formal element/mechanic), emphasizes perception and paying attention to what other players are doing (when we played, we each attentively watched each player take their turn to determine the saboteur). Although this is discussed by players, there is less discussion overall than in TbT (critique: mechanics should further emphasize discussion). Ultimately, both games promote Fellowship as an aesthetic (TbT by winning rounds with your team and having fun discussions/arguments and Stack by working to build a tower). Note: TbT also involves Fantasy (discussing imaginary worlds), while Stack involves Challenge (stacking dice).

Recall from earlier that both games have the goal of getting people closer to one another. Ultimately, TbT achieves this primarily by promoting players talking with each other about dark, philosophical topics and becoming comfortable with that. On the other hand, Stack does this by primarily promoting players observing/learning about each other. This ties back into TbT being a game more suited for people who already know each other (critique: they should note this formally, as, otherwise, there could be very awkward situations), while Stack, being serious, can be good for players just getting to know each other (critique: friends might not have the same incentive to play).